Editor’s note: Caleb Morell, assistant pastor of Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington, D.C., is author of the newly released book, “A Light on the Hill: The Surprising Story of How a Local Church in the Nation’s Capital Influenced Evangelicalism.”

For many modern Christians, Sunday School is primarily seen as a children’s ministry – a place where kids are taught Bible stories while their parents attend the main worship service. Yet historically, Sunday Schools played a far greater role. They were not only centers of religious education but also powerful tools for evangelism and church planting. Many churches – especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries – grew out of Sunday School missions, reaching communities that might otherwise have remained outside the church’s influence. I want to explore how Sunday Schools filled crucial social gaps, nurtured new believers, and laid the foundation for many churches still in existence today.

Poverty, illiteracy, and the need for Sunday Schools

The rapid urbanization and industrialization of the 19th century created an urgent need for education, particularly among working-class and immigrant children. In cities across America, many children had no access to formal schooling, and even fewer were exposed to regular religious instruction. Evangelicals saw Sunday Schools as an opportunity to reach these children, providing them not only with biblical knowledge but also basic literacy skills.

Many parents were reluctant to send their children to Sunday Schools, either out of skepticism toward religious charity or because they needed their children to work. Organizers had to canvass neighborhoods, persuade families, and often provide the most basic resources – chairs, books, even meals – to convince families to participate. As one 19th-century Sunday School teacher recalled, they had literally “to go out in the byways and the hedges and compel the people to come in that the Lord’s house might be filled.” Still, the Sunday Schools thrived, filling a crucial gap in both education and moral instruction. By memorizing Bible verses, catechisms and hymns, students not only learned Scripture but also developed habits of discipline and character formation that aligned with emerging middle-class values of self-control and hard work.

“The nursery of the Church”

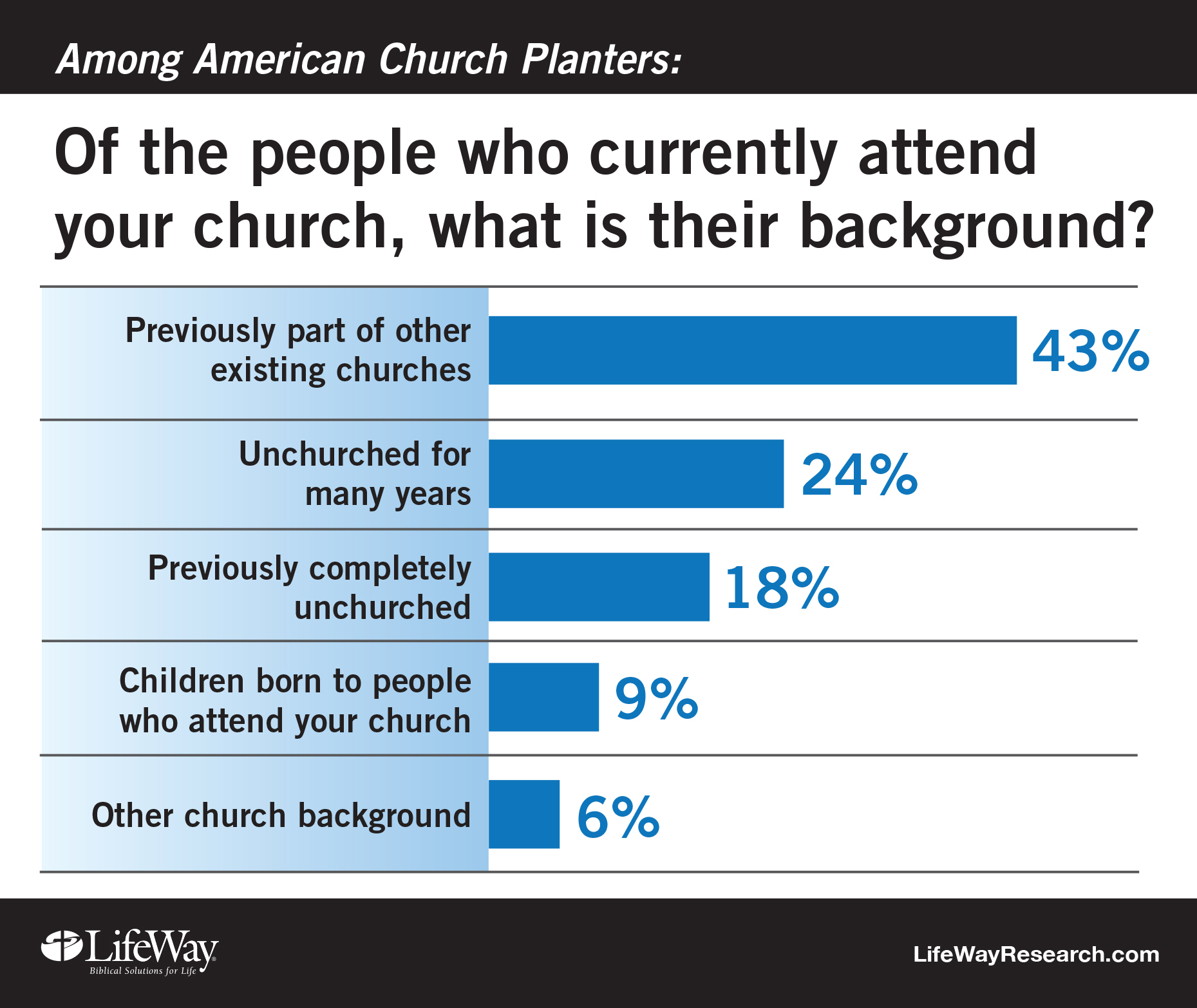

Sunday Schools were often described as the “Nursery of the Church” – places where young believers were nurtured in faith, with the hope that they would one day become full members of the congregation. Evangelists believed in the early conversion of children and saw Sunday Schools as an entry point for unchurched families. Historian Anne Boylan notes that “many churches formed around mission Sunday Schools,” with some estimates suggesting that two-thirds of churches in the northern U.S. had their roots in Sunday Schools.

One such church was Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington, D.C. In the years following the Civil War, Washington faced a severe housing crisis and rising poverty, particularly in areas like Capitol Hill. In 1867, Celestia A. Ferris called her friends together to pray for a Baptist church to be established on Capitol Hill. After several years of prayer, in 1871, Celestia Ferris and her small band of friends launched a Sunday School in a borrowed schoolhouse. They had no budget – parents brought stools and chairs for their children to sit on – but they had a vision for reaching the city’s children.

By 1874, the Sunday School had grown into the Metropolitan Baptist Association, with an explicit goal: to plant a church. Within a decade, the Sunday School had not only provided biblical instruction but had also laid the foundation for what became Capitol Hill Baptist Church. By 1884, one-fifth of the church’s membership had come through the Sunday School.

To keep the cost low, the association agreed to provide the materials. According to several accounts, Mrs. Ferris suggested to the Sunday School children that each child bring to the lot any bricks that they could find on the street or some vacant lot. They were carefully instructed to bring only “whole bricks,” the kind that may have fallen off a cart or been left in a lot after the completion of a building.

Enthused by Mrs. Ferris’s instructions, and no doubt eager to please their teacher, two of Mrs. Ferris’s little Sunday School girls visited a brickyard in the southeast section of the city and asked for a few bricks, which were given. When they later paid the yard another visit, the owner of the brickyard asked their reason. They explained that they were helping to build a church and that their Sunday School teacher had instructed them to collect bricks. At that, he told them that since they had been so noble, he was going to really help them and would send them a load of bricks. In this way, in a very short time quite a pile of bricks appeared on the ground, all in a most careful position and of a uniform size. Encouraged by their success, the two girls proceeded to visit two other brick yards, telling them what the first man had done. As a result, two more loads of bricks appeared overnight, one from each of the brickyard owners. As a result of the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the children, the only bricks purchased for the erection of the building were the pressed bricks used on the front of the building. How fitting for those very “living stones” – who were themselves the fruit of Mrs. Ferris’s prayers and labors – to play no small role in the erection of the chapel.

Sunday Schools were also key players in the expansion of churches in the western United States. The American Sunday School Union, founded in 1817, sent missionaries to establish Sunday Schools in newly settled territories. Many of these schools functioned as de facto congregations before formal churches could be planted. One missionary in 1859 claimed, “Most, if not all, the churches of the West of recent formation, have grown out of Sunday Schools previously existing.” In the absence of regular preaching, these schools acted as places of prayer, community gathering and spiritual instruction, proving that lay-led Sunday School efforts could have a lasting impact.

What can we learn from these examples today?

Sunday Schools were once powerful engines of evangelism and church planting. They filled critical educational and moral gaps, provided access to the Gospel for unreached communities, and laid the foundation for new congregations. Today, their role has largely shifted to internal discipleship rather than outreach. Yet history challenges us to reconsider their potential. What would it look like if Sunday Schools once again became mission fields? How might they be used to engage unchurched communities, nurture young believers, and even lay the groundwork for new churches? By learning from the past, today’s churches may find fresh inspiration for how Sunday Schools can once again become a transformative force in their communities.