In Support of Expansive Education

I saw a debate play out in the comments of a friend from college’s social media post the other week. It’s probably a scenario we’re all familiar with: someone posts a picture or an article, often a fairly innocuous one, that touches on a subject people have strong opinions on. And then the comments section goes wild; a commenter accuses the original poster of walking away from “true Christian faith,” and then the proof-texting with scripture verses starts, as poster, commenters, and bystanders all jump in with their opinions as to what a Christian should *really* think or do about the situation at hand.

The content of this particular debate isn’t really the point of what I’m writing here. What I was struck by, however, was the way in which my friend engaged. My friend was charitable in her reading of the words of others. She read Scripture holistically, pointing out the historical context for verses while carefully putting them in conversation with culture today. And as other college friends (people I haven’t seen in years) entered into the discussion, their responses were marked with the same thoughtful engagement with scripture and with culture. Clicking through their profiles indicated that most of these friends are still actively involved in the church; they attend different denominations across a wide spectrum, from high church to low, mainstream to evangelical. We all attended a small Christian school, and when I knew them personally, there was a lot less denominational variation in our affiliations. And yet all clearly still seek to follow Christ, personally and in their communities.

Protective or Expansive?

To me, this exchange encouraged reflection on the type of education we all received at our undergraduate alma mater, and how our time in college might have shaped this engagement. Perhaps this is because education has been in the news a lot lately, whether the dismantling of the Department of Education or bills about what can and cannot be taught. At the heart of many of these recent news stories and political discussions is a question about what education is for. Is education meant to protect children and young people from ideas that might be challenging or upsetting, or is it meant to expand their perspectives through engaging the society in which we live and its history, in its entirety? In short, should education (particularly a Christian approach to education) be protective or expansive?

If All Truth Was God’s Truth

This is not a new question––it is one that Christians have sought to understand since the days of the early church. Tertullian, a second-century Christian theologian, apologist, and polemicist from Carthage, famously asked in a text against pagan philosophy, “what has Athens to do with Jerusalem? What concord is there between the Academy and the church?” (Ch. 7, Prescription Against Heretics). It’s worth noting that Tertullian’s text was aimed at a very specific situation, where his opponents were intentionally mixing philosophy and Christianity to support and promote heresy. However, most patristic and medieval Christians took a different approach towards education and engagement with “pagan” philosophy, seeking to understand and engage with Greek, Roman, Persian, and (during the Middle Ages) Islamic thought as a way of better understanding Christ and Christian truth. In fact, it is out of this expansive approach to engaging with knowledge that the idea of a liberal arts education was developed: a collection of core knowledge that all should know, originally composed of the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, dialect) and the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy). Much of the material that medieval figures had available to them in these subject areas came from thinkers and philosophers working outside the Christian world– and yet, medieval Christians did not seem to think this was a concern, for if all truth was God’s truth, studying and learning could only ever point one closer to Christ. Engaging with culture was not something to be feared, but something that (whether you agreed with prevailing philosophical knowledge or not) was useful for learning the truth.

Expansive Engagement

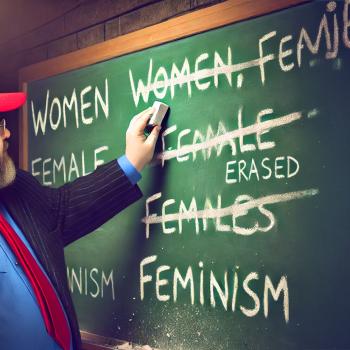

A number of more recent American models claim to follow this medieval model, focusing on “the classics” or “the canon” –– but increasingly narrowing that canon to include only white Christian (male) thinkers, with the justification that medieval or classical education would have only studied these figures. But this is a misreading of what classical and medieval education actually looked like: the point of medieval education was not to hide from things outside of western Christian culture, or to only read texts from a certain subset of thinkers, but to engage all knowledge from all experts, for the sake of better understanding God through philosophy, math, nature, music, and art. This is why we see figures like Hildegard of Bingen, a noted musician, theologian, visionary, and scholar of medicine and nature, held in such respect by women and men, laity and leaders alike. Learning broadly was the sign of one who sought to know God fully, and learning was not limited to a certain type of knowledge from a certain type of person. The sign of a good Christian thinker was their expansive engagement with all types of people, philosophies, and texts.

Protection As Opposed to Engagement

This modern American framework for what a classical Christian education means is an important change in mindset, and one we often miss: classical and medieval approaches to Christian education engaged culture and its prevailing philosophical assumptions fully and broadly, not seeking to protect Christians from principles (or people) that seemed antithetical to faith, but instead to understand God, who created and moved through all things, including the culture in which they lived and learned. Medieval education was both exhaustively expansive and systematically grounded in faith. Modern models of Christian education might express some of the same goals, of engaging the culture for Christ, but often do so solely by explaining why the culture is wrong rather than seeking to understand and learn from it. The recent model seems to be for an education that protects: early private Christian schools in the US sought to protect students from feared policies (and people), emerging as a response to desegregation, and the same trend of protection as opposed to expansion continues in discourses like a recent one in Christianity Today about public, private, or homeschool education. A Christian education, at least in our modern American context, now seems to mean protection as opposed to engagement.

Young Adults Left The Church

And a lot of Americans have received some form of Christian education as they grow up. A Pew Research study from February highlights that at least 69% of Americans received at least some form of religious education, with upwards of 8% of all Americans attending private religious school for a year or more. This statistic sits uneasily alongside Pew Research’s study from March, which shows that many people around the world are walking away from their childhood religions. Around 28% of all adults in the US no longer practice the religion they were raised in, and Christianity has seen the largest percentage of religious disaffiliation (around 19%). Those most likely to disaffiliate are younger adults. While it’s difficult to break down these numbers or connect them to a single causative factor, given the high percentage of Americans who received some form of religious education and the high percentage of young Americans disaffiliating from the religions of their childhood, it seems likely that many of these individuals walking away from the church were educated in systems that sought to protect them from ideas that might challenge their faith. While advocates for protective education might argue that an expansive education is the cause of this, a (now somewhat dated) study from 2011 identified overprotectiveness, shallowness, and antagonism to science as the top three reasons that young adults left the church.

Education is No Threat to the Truth

Much has changed in American Christian culture since 2011, and there is much that could be said about these numbers. But I still think it seems fair to say that fundamentalism in education– whether religious or political– often creates worldviews that shatter. Perhaps we’re missing the key question in these debates about Christianity and education. If our concern is protecting a specific cultural, political, or denominational position, yes, then an education that encounters and engages all texts and ideas is going to be a threat. But if our goal is not a worldly kingdom, but a heavenly one– an expansive education is no threat. Engaging with the ideas and history of the culture and society in which we live, in their entirety (yes, even the parts that we feel reflect badly on the church, or that seem to conflict with our understanding of rightly live faith!) ultimately is no threat to the truth of the gospel. An education that searches broadly and deeply and diversely ultimately does what we as Christians hope to do: teaches us to love God and love neighbor (Matthew 22:34-40, Mark 12:28-34) and to take every thought captive to Christ (2 Corinthians 10:3-5). Those of us who are teachers would do well to remember this. Those of us who are parents making choices about educating our children should remember this as well. And all of us should remember this in political debates about what sorts of education should receive our support.