I’d never heard of these POWs before – all those Great Escapes & never a brown face among them.

So what was the experience of Indian POWs after their return home, the Épinal escapers and the others? The truth is that they weren’t feted and greeted and welcomed back as heroes at the end of the war, nor with the passage of time.

Regimental Monthly Intelligence Reports were an essential government tool for taking the temperature of army and civilian opinion, and the reports from the Artillery Depot in Deolali are revealing. Unlike British servicemen (who were mostly conscripts), Indian soldiers were not demobilised quickly at the end of the war, and having seen British troops close up, they had many reasons to grouse about the comparison. The Artillery Depot reported grumblings about money, medals and general morale. A common complaint was ‘why does the [Indian soldier] get less pay than the [British soldier] when both fight in the same war and we say we were better?’ In June 1945, the problem was more specific: some of the Épinal escapers (there were twenty-four from the artillery)had been waiting for their back pay over six months

There was also bad feeling about medals and awards. There is some evidence that the British were more generous at the end of the war than usual, in an effort to counteract the popularity of the Indian National Army and the general drift away from the Raj. Conversely, some ex-POWs in the artillery were disappointed not to receive the Jangi Inam – a category of gallantry award that carried a pension continuing to the next generation.Unsurprisingly, in these conditions, morale among returning POWs was low.

Another report from Deolali made unfavourable comparisons between POWs coming back from Germany and those captured by the Japanese (FEPOWs).This contrast was repeated elsewhere. FEPOWS were seen as being more docile because they had been treated so much worse, while those from Europe were demanding promotions. The whole picture was further complicated by press reports about the INA prisoners, ‘Some apprehension is felt by all Ranks as a result in the press suggesting that INA personnel may be instated in the services by the new Government and that such men may be given seniority higher than that of loyal ex POWs’.

All of this contributed to a post-war atmosphere leading to a series of upheavals in the military, which ‘could not be insulated from the political changes’. The men identified as ‘black’– those who had joined the German or Japanese armies – were imprisoned in the Red Fort in Delhi. Three senior officers were put on trial for treason, found guilty but released soon after in the face of public pressure.

Shortly afterwards, the Royal Indian Navy at Bombay and Karachi mutinied, although they returned to their ships after a week. The British grip on the South Asian military was loosening: being an ex-POW in India just after the war was not something that accrued respect or many chances for advancement. There are very few sources of information on the long-term impact of their imprisonment on these men and few non-officers recorded their experience. One Épinal escapee interviewed in Switzerland talked about how he felt in the weeks since the bombing, ‘I have never regained my inner happiness since’. We can only hope that his inner happiness was restored with the healing passage of time.

Unlike in other Commonwealth countries, there do not seem to have been any ex-POW associations formed or newsletters established. Dr Santi Pada Dutt refused to tell his family why he had been awarded the MC, replying, ‘Well, I just did my work and they gave it to me’. His daughter, Leila Sen recalled:

My father never spoke about any of this to the very end of his life; and even then, not until I began probing him about his war experiences. As a child and a teenager I didn’t question the source of the disturbing nightmares he suffered every so often, and by my late teens they occurred less frequently. I grew up with this man who, in my small world, was just my father – a wonderful father, but no more and no less. And only in our last years together did I come to realise that beyond being my parent he was also someone who had volunteered to do his best in a time of world turmoil and, little as that may have been, I would find it archived in the museums and histories of countries other than his own. It will always amaze me and renew my appreciation for his humility and humanity.

There were other long-term effects. Sahibzada Yaqub Khan had ‘positively spartan ideas on food. The only time he ever mentioned his POW years was when he lectured over-indulgent me, on the virtues of eating less.’ There were physical scars as well – Taj Mohd Khan of the 2nd Royal Lancers carried the marks of German bayonets. Subedar Jit Singh Sarnafrom Rawalpindi bore mental scars and:

… could not shrug off the memory of his stay in Oflag 79. The melancholy of those days was captured in a pencil sketch of his camp boots that Jit gifted his nephew in 1968. The sketch still hangs at the Sarnas’ residence. Unable to forget the days of shame, Jit would cry before his family while recollecting how the Nazi soldiers would stop the train, force prisoners to defecate by the railway tracks in a row, and take photographs and laugh over it.

Some ex-POWs reported positive impacts, however. Anwar Hussain Shah of the 22nd Animal Transport Company, who probably joined the German 950 Regiment, used to receive letters from Germany, offering him jobs. His family considered that he had gained:

… knowledge and experience from his time in army and prison. He became disciplined. He had an ocean of social, political and financial knowledge. He was a great intellectual. He learned history and had expertise on our national poet Allama Iqbal. All the knowledge he gained was from his time in the prison.

Many prisoners had learnt languages. At the Bengal Sappers & Miners’ HQ at Roorkee after the war, ‘there were men who could carry on a conversation in German, French and Italian as well as Urdu and English’. The Italian filmmaker Roberto Rossellini was visiting Indiain the 1950s and got stuck one night on a highway. When a truck didn’t stop to his waving, he swore at the driver in Italian. To his surprise, the Sikh driver poked his head out to shout back at him in the same language.

The driver had spent several years in an Italian camp and had used his time wisely. More generally, the veterans of Stalags and Oflags became building blocks in post-war South Asian societies – generals, ambassadors, farmers, teachers – bringing back what they had learnt in Europe, their enhanced political and social awareness helping to build their new countries.

Apart from Anwar Hussain Shah, others stayed in touch by letter, at least for a short while. Jules Perret mentioned letters from Indians who had sheltered in Étobon. Sohan Singh was taken prisoner in North Africa at the age of 18 and spent three years in Annaburg. He stayed in touch with the farmer he’d worked for in Germany, writing to him in passable German. A local historian from Annaburg started to visit him in India and newspapers in Germany carried his reports. Singh always wished to return to Germany but was unable to.

Others did manage to return to Europe, as Yaqub Khan did in 1985 when he was Pakistan’s Foreign Minister, giving a speech in Italian. R.G. Salvi also went back to Italy, taking his wife Hansa with him, to see the people who had sheltered him over the winter of 1943–44. Hansa writes of the trip as if it were a pilgrimage, visiting old hiding places and ‘following our Indian custom of sitting for a while on the steps of the temples that we visit, revering them and trying to establish a rapport with those that lead us to [god]’.As they left, she had a realisation that ‘I owe them more than I can ever repay.

But it worries me no longer for I realise that these very obligations are the eternal link between us.’ This sense of gratitude must have been widespread among those Épinal escapers who had passed through Étobon and other French villages. Other prisoners – like Barkat Ali – never left Europe. Their physical remainsare buried in cemeteries, scattered in rivers or fields, or still lying hidden in a forest or under a post-war building. Of the 6,000 European graves and memorials to Indian soldiers on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website, there are 248 named soldiers whom I have identified as POWs (although they are not marked as POWs by the Commission). They represent the counterpoint to the British graves in Pune, Rawalpindi and across South Asia – Empire soldiers far from home.

The French national cemetery at Épinal is a large one, on the hills to the east of the town. There is a large Christian civil section, a smaller Jewish section and a large enclosure at the top for French military graves, mostly from the First World War. Right up in the top corner

is a row of limestone headstones, conforming to the standards of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. There are seventy-one in total, all Indians. Sixty-six of them are dated 11 May 1944: they died during the air raid. Of those, eleven stones bear the inscription ‘A soldier of the Indian Army 1939–1945 is honoured here’ – meaning that those

bodies were never identified.

There are Muslims and Gurkhas here, Hindus and Sikhs. Some are very young – Kartal Singh of the Bengal Sappers & Miners is recorded as being just 16, so could have been as young as 14 when he was captured. The bodies of the Sikhs and Hindus were cremated, and the ashes scattered in the Canal des Grands Moulins, and their stones stand as memorials. Seven birch trees are arranged nearby in a circle, and as I photographed the graves, a blackbird settled on one of the headstones. Life continues among the dead.

Those seventy-one graves are not the whole story, however. In late 1945, an Indian Military Mission opened in Berlin, charged with tracing missing POWs and locating graves. From August to December 1946, they supervised excavations of bomb craters at Épinal. Sixty-four bodies were found, but most were not identified. The mission completed its work in 1946 with 125 men still listed as missing. The work of locating them continues.

In 1954, a grave marked ‘Un Français Inconnu’ (‘an unknown Frenchman’) was dug up and found to be wearing British khaki. In due course, he was identified as Dafadar Jodha Ram from Chauki Kankari, near Hoshiarpur, and he was later reburied at Épinal. More recently, the headstone of a soldier from the Baluch Regiment was discovered in a ditch in Waregem in Belgium. It turned out be a duplicate of that of Salim Makhmad, killed on 11 May in the bombing of Épinal. How it came to be in that ditch, 400km north-west of Épinal, is yet to be established.

The memories continue to haunt. When the authorities in Épinal started excavations for a new gendarme barracks next to the site of the camp in the 1970s, several bodies of Indian soldiers were discovered.In the woods near Chenebier, a landowner who was planning to sell a parcel of woodland changed his mind when he looked at the raised mounds among the beech trees, thinking that there might still be Indian bodies buried there.

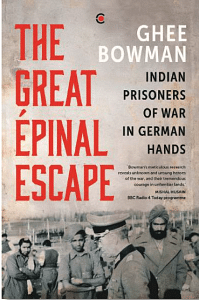

This excerpt from ‘The Great Épinal Escape: Indian Prisoners of War in German Hands’ by Ghee Bowman has been published with permission from Context, an imprint of Westland Books.

This excerpt from ‘The Great Épinal Escape: Indian Prisoners of War in German Hands’ by Ghee Bowman has been published with permission from Context, an imprint of Westland Books.