It’s fun to frolic amid art and nature in Thailand’s newly opened Khao Yai Art Forest, but it might yet take some time for this utopic enterprise to bloom

“Maman is a spider and a mother, a nest and a prison. Yet for the first time, here in the jungle, the spider appears for what it is: a bug in the grass.” Stefano Rabolli Pansera, the debonair director of Thailand’s newest contemporary art attraction, Khao Yai Art Forest, is talking about the last work of this afternoon’s preview tour. As he waxes lyrical about Louise Bourgeois’s iconic nine-metre-tall arachnid, I weave between its spindly bronze legs and drink in our surroundings: the newly seeded rice fields and rolling hills of a private plot of land located close to one of the country’s most popular weekend retreats, Khao Yai National Park (a roughly three-hour drive from Bangkok). Normally this sculpture looms menacingly outside museums or towers, but here it seems almost to be guarding the site, its maternal and territorial instincts kicking in.

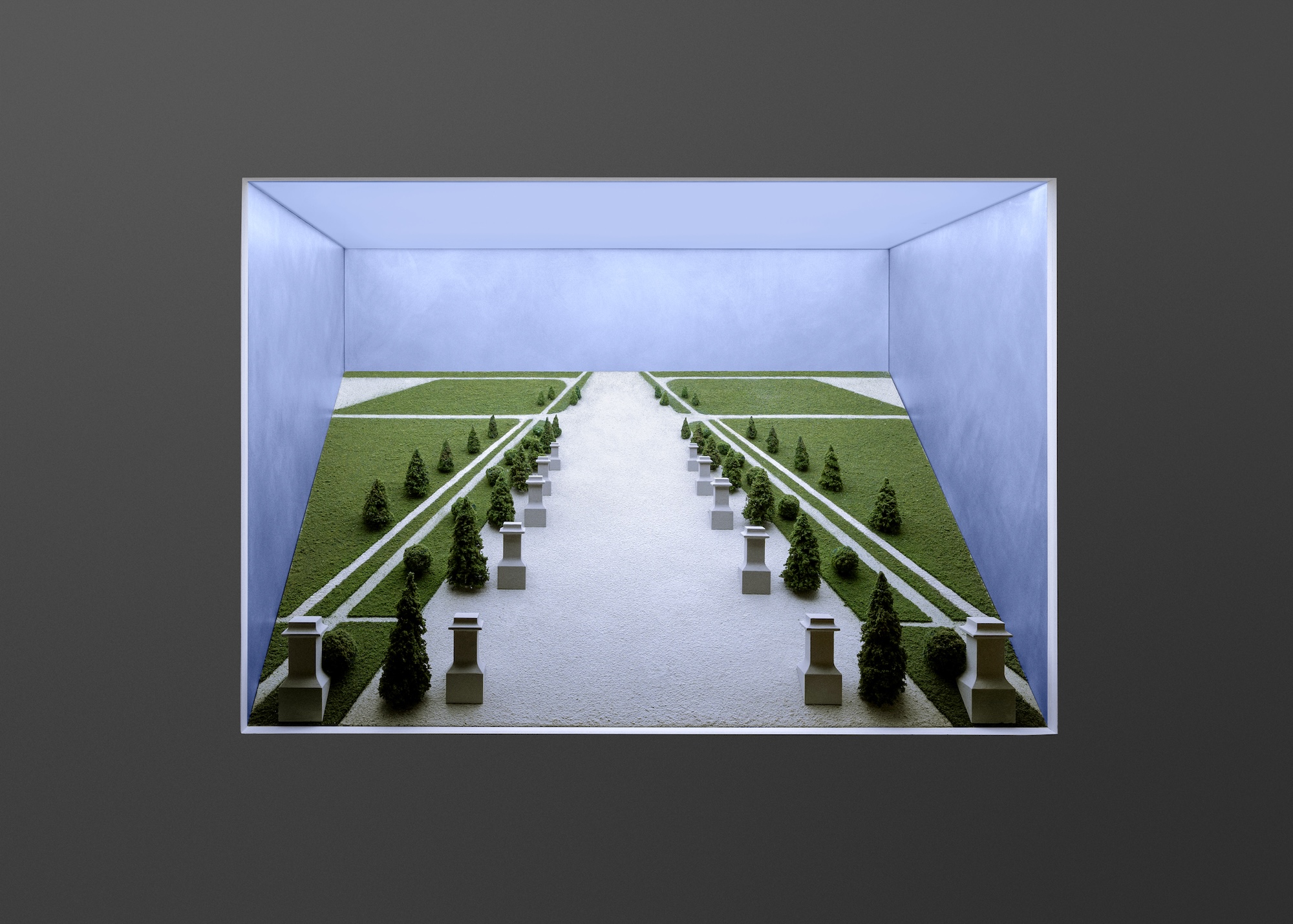

Close encounters with Maman (1999–2002) are currently a cornerstone of what is being touted as a ‘transformative cultural destination in Thailand where contemporary art and nature exist in perfect harmony’. But while this work is on loan (from the Easton Foundation), other sculptures are permanent features of Khao Yai Art Forest’s 85 hectares. Francesco Arena’s GOD (2024) comprises two granite boulders, each with a flush-cut face. The letters ‘G’ and ‘D’ are apparently engraved on one face, and ‘O’ on the other, but, with both boulders elegantly stacked amid young trees, these letters are invisible – much like the titular subject.

Nearby, a gentle hillside that resembles Teletubbyland is enveloped in clouds of artificial mist as we walk up it. Harvesting atmospheric moisture using renewable energy, Fujiko Nakaya’s Khao Yai Fog Forest, Fog Landscape #48435 (2024) is ‘a form of Land Art 2.0’ according to its description, because it ‘reveals latent forces within nature itself’ rather than imposing forms onto it. But encountering mist as medium – feeling the cool droplets on my skin and momentarily losing my girlfriend – elicits childish play and wonder, not thoughts on the interplay of wind, temperature, humidity and pressure, nor the connotations for Land art practices at large.

Among the takeaways from my time at Khao Yai Art Forest, one of the most unambiguous is that today is the beginning of a long journey, not a grand opening. Its Thai-Korean founder, Marisa Chearavanont – a philanthropist and art patron married to the chairman of one of Thailand’s largest companies, CP Group – hopes to create something fluid, amorphous and evolving. And as with her one-year-old project in the Thai capital, Bangkok Kunsthalle – the disfigured former printing factory turned art space where exhibitions are guiding its floor-by-floor revival – this process is to be artist led. “We invite local or international artists to be inspired by this land and to create work that resonates with hope, nature and healing”, she says. “And to use all the mediums they can find here: water, soil, sun and wood.”

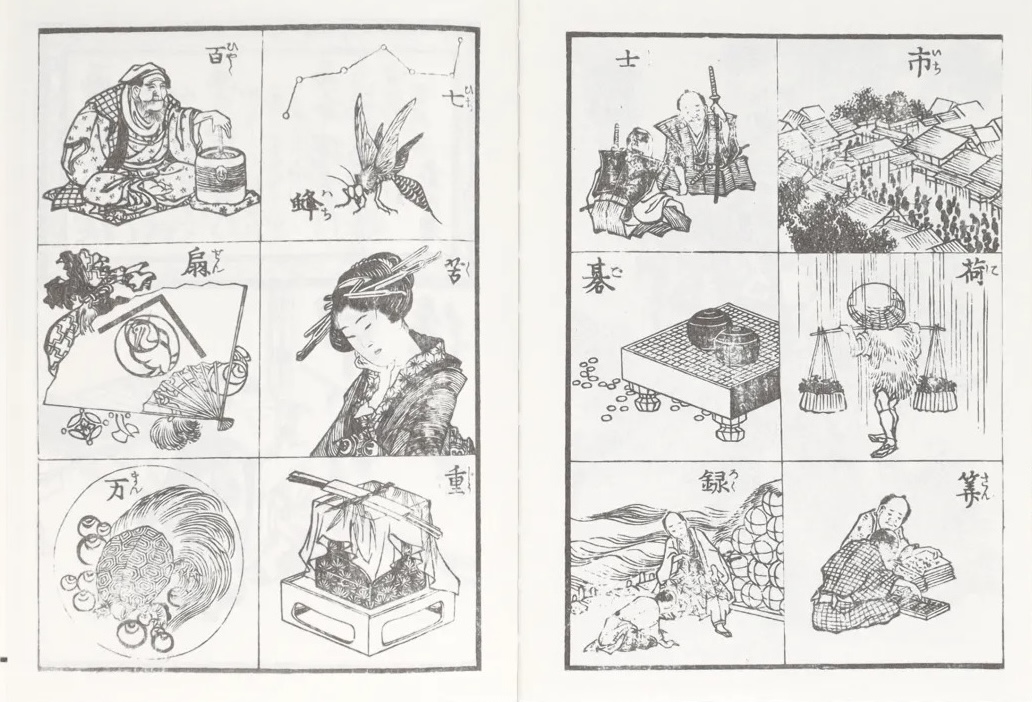

The most thoughtful response to this invitation thus far is a site-specific work consisting of ten ersatz Buddhist monuments – fragments of dome-shaped stupas – made from soil. Encountering its lichen-covered elements along a dirt track, secreted in corners of a sloping forest, Pilgrimage to Eternity (2024) strikes a chord with me. Thai artist Ubatsat has ceded its upkeep to the environment – and in so doing has channelled the erosion, neglect and ruin that afflicts many a sculpture park into a Buddhist-inflected talking point. How will nature receive this work? And what will Khao Yai Art Forest’s facilitation of this reception teach us about its rapport with nature?

Time will tell, of course, but as things stand, a conspicuous gap exists between its aspirational rhetoric and its physical manifestation. In interviews, Chearavanont tells a heartwarming story: recounts how the big old trees on this land were cut back by farmers during the 1970s, who then grew tapioca and corn for several decades before selling up; explains that her decision to buy and restore this tired land was the result of an epiphany she had during the COVID-19 lockdowns, when forest strolls led to a newfound appreciation for nature. The healing it provided, and her desire to return the favour, is this project’s leitmotif. “Healing is the compass for our interventions”, Pansera explains over refreshments beside Richard Long’s Madrid Circle (1988): a perfect circle of slate slabs located on a plateau overlooking the recovering forest. Add to these arboreal reveries the artworks by internationally prominent artists, and the input of notable others (in December 2023, Haegue Yang, Ernesto Neto and Michael Elmgreen joined a ‘Forest Circle’ workshop to hash out potential models, for example), and you have a project seemingly precision-tooled to draw the admiring gaze and superlatives of art publications, newspapers and art fans – but by no means guaranteed to meet its own high-flown aims.

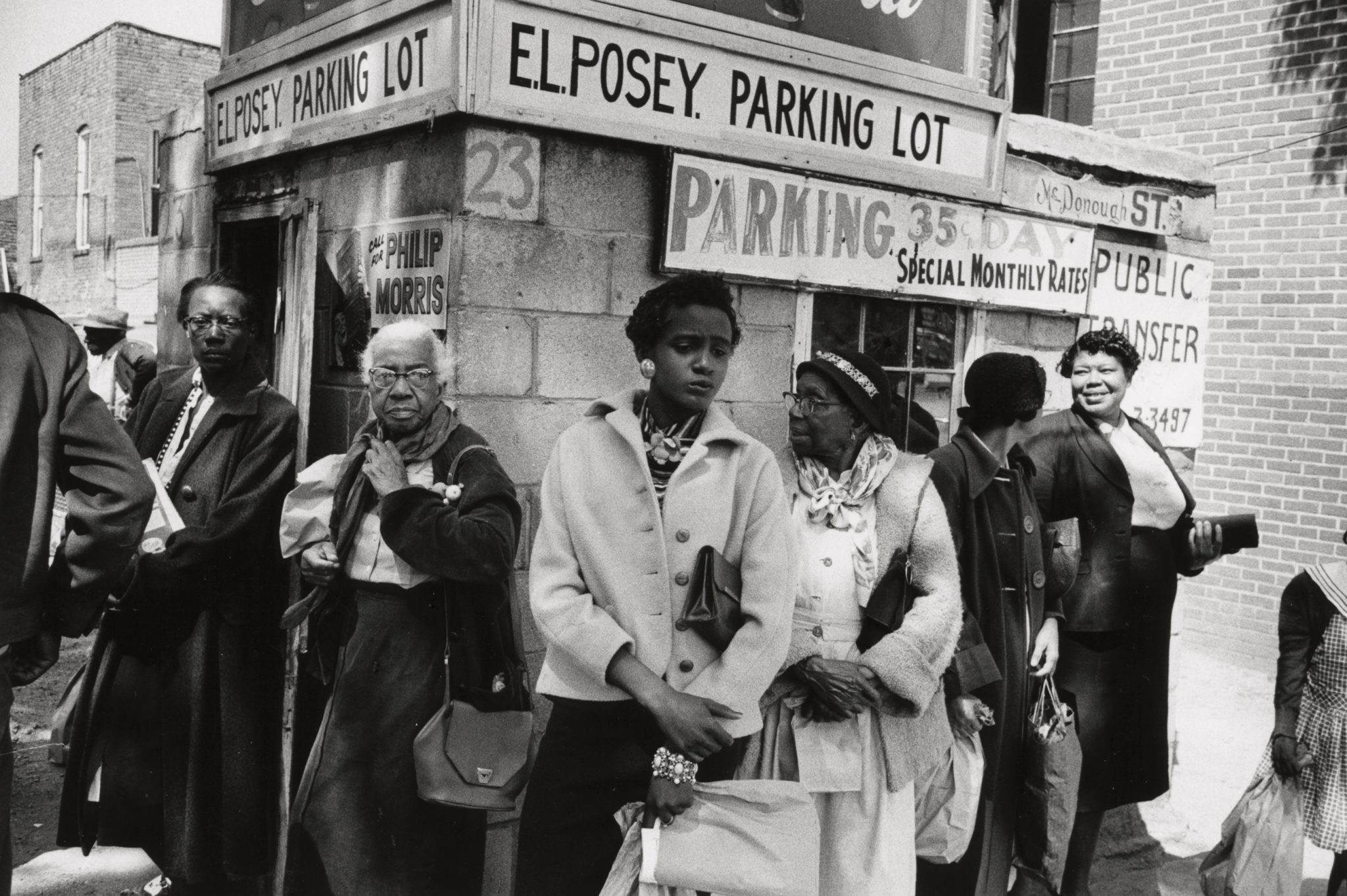

Exploring the site, and listening carefully, I sense that Khao Yai Art Forest’s fictional form is taking shape faster than its actual form – the perception created by all the articles, interviews and Instagram posts is not yet matched on the ground. And this leads me to draw comparisons with more unassuming yet proven models: the nearby Jim Thompson Farm’s long-standing Art on Farm season in December, for example, when its fields host works by local names. And to mull over recent history: northern Thailand’s dormant The Land Foundation, founded by Rirkrit Tiravanija and Kamin Lertchaiprasert in 1998, for instance. While not an overtly public-facing project (unlike Khao Yai Art Forest, which costs 500 baht, or £12, to visit), this working farm speckled with structures built by international artists and artists’ groups cultivated, during its lifespan, an image that distracted from its functional failures, the art historian Clare Veal argued in a 2014 paper, and ‘disintegrated into didactic assertions of the project’s excellence in and of itself’.

Given Chearavanont’s ties to the CP Group – an association that has led some to note the similarity between Nakaya’s fog landscape and the blight that is cornfield burning in Thailand (something the conglomerate is trying to curb among its contract farmers) – Khao Yai Art Forest’s efficacy and assertions of excellence are likely to be picked apart with relish, and in perpetuity, whatever unfolds. But while a question mark surrounds its self-styled credentials as a ‘pioneering interdisciplinary institution’, one thing is already certain: it has a sense of humour.

As dusk falls, we squeeze into a suave drinking den, replete with six red leather stools, terrazzo flooring and an original Martin Kippenberger hanging by the entrance. Cocktails and conversations flow, although the bonhomie here this evening masks a hyper-exclusive door policy: K-BAR (2024) is open but once a month, so most visitors are only going to be able to press their faces up against the windows. Upending expectations, this site-specific installation is, I read later, a new example of what its creators, Elmgreen & Dragset, call ‘denials’. But in the moment, it feels like confirmation of a truism: whenever the artworld declares its idealistic or utopian ambitions, its excesses and paradoxes are rarely far behind.

From the Spring 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy