Caste in West Bengal: Invisible or ‘unrecognised’?

The conspicuous absence of caste in the public consciousness of Bengal is accompanied by an equally noticeable lack of a consolidated lower-caste or Dalit movement in the region. This, despite the fact that West Bengal has the second highest percentage of Dalit population in India.

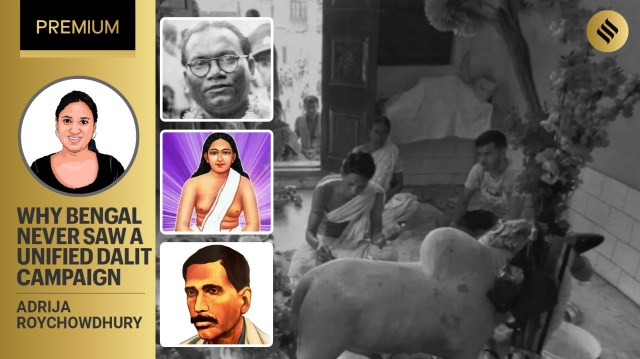

From top Jogendranath Mandal, Harichand Thakur and Mahendranath Karan (edited by Abhishek Mitra)

From top Jogendranath Mandal, Harichand Thakur and Mahendranath Karan (edited by Abhishek Mitra)In March this year, 550 Dalits in Gidhagram, a small village in West Bengal’s Purba Bardhaman district, entered a local temple for the first time. The incident has reignited discussions on the issue of caste-based discrimination in a state that has for long, and in popular consciousness, been considered as ‘casteless’.

But is caste indeed absent in West Bengal, or is it merely absent from public discussions? “I would say that caste has been unrecognised in Bengal, and that there was a conscious effort to do so,” says historian Sekhar Bandyopadhyay in an interview with indianexpress.com.

That caste has evolved differently in the region from the rest of the country, or that the absence of a Dalit movement in the state along with the existence of a long period of Communist regime that insisted on class and not caste being the primary basis of social stratification are all factors responsible for the lack of public consciousness about caste-based discrimination in Bengal.

The evolution of caste in Bengal

Experts point out that even though caste has been a social reality in Bengal, much like the rest of India, the rigours of the system were not strict in the Bengali-speaking region. This was due to certain historical factors. “To begin with, Bengal was distant from the core geographical area of Brahmanism,” explains Bandyopadhyay.

The members of Dalit family entered a temple at Gidhagram in Purba Bardhaman and offered Puja for the first time amid heavy police protection. (Express Photo: Partha paul)

The members of Dalit family entered a temple at Gidhagram in Purba Bardhaman and offered Puja for the first time amid heavy police protection. (Express Photo: Partha paul)

Moreover, when Brahmanism started gaining currency in the region from around the 11th century, it was constantly interacting with the more liberal tribal culture of the region. Bandyopadhyay, in his book Caste, Culture and Hegemony (2004), notes that “the dominance of the Brahmanical religion was further contested by Buddhism under such ruling dynasties as the Palas between the eighth and twelfth centuries, the Kambojas in northern and eastern Bengal in the tenth century and the Chandras in Eastern and Southern Bengal between the tenth and eleventh centuries.” After Buddhism there was also the ascendancy of Islam in the political sphere which kind of toned down the oppressive aspects of the caste system.

It was only in the 12th century that there was a resurgence of Brahmanism in Bengal which led to the formalisation of the varna social organisation. However, the emergence of the Bhakti movement in Bengal in the 14th and 15th centuries once again had a corroding effect on the caste apparatus. “During the Bhakti movement, the Gaudiya Vaishnavism movement founded by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu underscored devotionalism over ritualism. It galvanised underprivileged castes and overshadowed ritualistic Brahminism,” explains Arup Chatterjee, professor of English Literature at OP Jindal University.

Chatterjee summarises Bengal’s position vis-a-vis the caste system as it operated in the rest of the subcontinent: “Bengal’s long association with Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam (and later the Dutch, Portuguese, Danish, French, and British) ensured that the society evolved pluralistic codes and idiolects over checks and balances within one religious identity.”

The 19th century in the Indian subcontinent was specifically characterised by social reform movements, a large number of which was focused on the eradication of caste discrimination. The Prarthana Samaj in Bombay and Jyotirao Phule’s Satyashodhak Samaj, for instance, were focused upon abolition of caste inequalities and the upliftment of the Dalits. The ‘Bengal Renaissance’, as the 19th century reform movements in the region is popularly called, had its major weakness in the fact that it did not focus on caste at all. “At the same time it did not openly support extreme form of caste oppression or untouchability,” says Bandopadhyay. He refers to the writings of Vivekananda and Rabindranath Tagore in which they wrote about the evil of untouchability that needed reform — an idea that was legitimised later by Mahatma Gandhi’s Harijan movement.

One must also consider the distinct nature of land ownership among the upper castes of colonial Bengal. Social scientist Anjan Ghosh, in his article Cast(e) out in West Bengal, explains that as result of the Permanent Settlement Act of 1793, the upper castes, namely the Brahmins, Kayasthas and Baidyas, came to control most of the land but functioned mostly as absentee landlords. “Land was a productive asset that yielded substantial rent. But they were neither directly engaged in supervising agricultural production nor increasing productivity,” he writes.

As residents of urban areas in Calcutta or district towns, they were detached from agricultural pursuits and instead were the first beneficiaries of English education, allowing them to develop a stronghold over jobs and professions. “The upper caste bhadraloks (as the English educated Bengali elite came to be called) have since exercised undisputed authority in the public realm,” writes Ghosh. The bhadralok’s lack of acknowledgement of caste is “one of the main reasons why the institution has remained invisible in Bengal,” argues Manas Patra, a research scholar at the Indian Institute of Technology in Gandhinagar.

Chatterjee further illustrates that while bhadraloks may be seen to have been the main beneficiaries of opportunities for Western education and cosmopolitanism, their integration of ostensibly non-Indian ways of life in diet, marital practices, social codes, and educational reforms had a strong percolating effect. “To this new sensibility that began emerging in the late eighteenth century, caste was a highly odious category to recognise in social life,” he says.

The (lack of) a consolidated Dalit movement in Bengal

The conspicuous absence of caste in the public consciousness of Bengal is accompanied by an equally noticeable lack of a consolidated lower-caste or Dalit movement, of the kinds that occurred in Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh or Bihar pre- and post-independence. This is despite the fact that Dalits comprise 23.51 percent of the total population of West Bengal (according to the 2011 census of India). The state also has the second-highest Dalit population in India at 10.66 percent.

Ghosh asserts that both the intermediate peasant castes as well as the Scheduled Castes were “too dispersed and fragmented to pose any challenge to the upper caste bhadralok.” He points to the case of the Namasudras, who were the most organised among the Scheduled Castes. In the wake of Partition, the Namasudras, who mostly inhabited districts of East Bengal, migrated to West Bengal in large numbers. Thereafter, most of them settled in the border districts of Nadia and 24 Parganas. The later migrants were settled in the Andaman Islands and Dandakaranya in Madhya Pradesh (now in Chhattisgarh).

“Dalit identity was regionalised in Bengal,” suggests Bandyopadhyay. Before 1945, he points out, there were three regions where the Dalit movement was particularly powerful. This included the Namasudra community in East Bengal, the Rajbanshis in North Bengal, and Paundras in South Bengal. However, there was no pan-India Dalit identity until the very late colonial period.

It was only in 1945 that the Bengal branch of Ambedkar’s All-India Scheduled Castes Federation was formed. Jogendranath Mandal, a formidable member of the Namasudra community rose to become the first leader of the federation, attempting to give a pan-Bengal Dalit identity. Mandal was largely responsible for Ambedkar’s historic election to the Constituent Assembly of India from the Bengal province.

However, the Ambedkarite movement had a limited impact on Bengal, compared to the northwest and south, and the Bengal Dalit movement spearheaded by Mandal quickly faded away after Independence. One of the reasons for this, suggests Bandyopadhyay, was that the beginnings of the Ambedkarite movement in Bengal coincided with Partition. “The Scheduled Castes were immediately polarised. A large section among them allied with Mandal and the Muslim League. But another section, mostly comprising a large number of Namasudras, afraid of Muslim rule, aligned with the Congress and the Hindu Mahasabha,” explains Bandyopadhyay.

Yet another factor that contributed to the disappearance of the Dalit movement in the region was the emergence of the Communist regime in later years. “Communism offered Dalits an Overton window to remedy economic exploitation and discursive land reforms. However, the communist emphasis on the ‘proletariat’ as an ontologically economic category ensured that Dalitness was not recognised as a disruptive political category,” suggests Chatterjee.

Till date Ambedkar remains a distant figure among many Dalit communities in Bengal. Patra, who has been studying the Bauri community in South Bengal, says that through his research he has concluded that a substantial number of peripheral Dalits in the region never heard of the name of Ambedkar.

Even when a consolidated Dalit movement would appear to be missing in the region, more recent scholarship has pointed to a vast body of Dalit literature from Bengal from as early as the 17th century, which they say has not been documented in the English language.

Mahitosh Mandal in his research paper Dalit resistance during the Bengal renaissance: Five anti-caste thinkers from colonial Bengal, India (2022), writes, “Whereas there are hundreds of pages written by the Dalits in the vernacular Bengali language that document Dalit history, hardly any professional historian has referred to these.” One example he cites is the Poundra Mahasangha, produced by the Poundra community containing autobiographies, literary writings, and political pamphlets, which can give a fair idea of the anti-caste struggle of this group.

Mandal cites five other Dalit leaders: Harichand Thakur and Guruchand Thakur of the Namasudra community, Mahendranath Karan and Rajendranath Sarkar of the Pundra community, and Mahendranath Mallabarman of the Malos, whose intellectual output was committed to the anti-caste and self-respect movements.

Patra explains that most of this literature exists either in oral form or in local Bengali dialects which is different from the Bengali written and spoken in elite, urban regions of Bengal. Consequently, most of this literature remained restricted to the rural areas and mofussils and could not reach the markets of Calcutta urban literature.

The Communist Party and class instead of caste

The prolonged rule of the Communist Party in Bengal is perhaps held responsible for caste issues not being recognised in the region. In terms of its ideology, the Communist Party viewed society through the prism of class and not caste. “Caste was not absent, but it was subsumed under the broader framework of class politics,” suggests political scientist Ayan Guha, who has authored the book, The Curious Trajectory of Caste in West Bengal Politics (2023).

Guha explains that there are two separate but interlinked positions that Communist politics takes on caste. The more orthodox position asserts that economic class is the base of society, whereas caste is part of the superstructure. Consequently, any change or progress in caste relations can only be made once there is a change in the base, which is economic class. The other position believes that in Indian society, caste is a form in which class expresses itself.

Keeping in tune with their ideological positioning, the peasants, rather than the lower caste groups, always formed the unit of political mobilisation for the Communist Party in Bengal, be it for their land reform movements in the 1970s or the institutionalisation of the Panchayat system.

This focus on class was established firmly by the West Bengal government in front of the Mandal Commission as well. In August 1980, the Bengal government had formed a committee to look into the issue of caste backwardness in the state. It maintained that “poverty and low levels of living standards rather than caste should, in our opinion, be the most important criteria for identifying backwardness.” The committee’s report emboldened chief minister Jyoti Basu to remark before the commission that in West Bengal there were only two castes — the rich and the poor.

“Since there was no caste-based mobilisation, Bengal bucked the Mandalisation of politics that happened in other parts of the country since the 1970s,” says Guha, adding that apart from the Left rule there were a few other factors as well that played a role in ensuring that there was no pushback from the lower castes against the dominance of upper-caste dominated politics in Bengal. “Firstly, the landholding class in Bengal is composed of diverse caste backgrounds. There are many among the lower castes and intermediate castes as well who are land holders. Consequently, caste-based mobilisation became difficult in rural society,” he says. “Further, the average size of landholding in Bengal has historically been lesser compared to other states. It means that there is not a stark difference in the average size of landholdings between the upper and lower castes.”

The absence of caste-based political mobilisation though has not been a deterring factor when it comes to discrimination or even violence against the lower castes in the region. The massacre of hundreds of Dalit refugees at Marichjhapi, an island in the Sundarbans, under the Jyoti Basu-led Left government in January 1979, remains one of the darkest reminders of brutality upon the lower castes in the region.

Thereafter, there have been several other reports of caste-based discrimination in Bengal. A 2010 survey report published by Pratichi India Trust in association with UNICEF Kolkata found that in some schools of Bengal, Scheduled Caste students were forced to sit separately. Ghosh, in his article, cites another report concerning the Doms and the Hanris (both Scheduled Caste groups) belonging to Rohini village in Jhargram. “For many years after Independence, they had to wear bells around their neck whenever they ventured outside their locality (para) to forewarn the upper castes of their approach,” he writes.

Experts suggest that since the emergence of the Trinamool Congress in 2011, caste-based group identities appear to be gaining prominence. The notable rise of the Matua Namasudras in Bengal’s electoral politics in recent years is a case in point. Guha, however, suggests that it is debatable if we can consider the resurgence of the Matuas as an articulation of caste-identity. “It is not conventional caste politics, since this group is not being mobilised as a caste group,” he says. “Rather, it is being mobilised as a Hindu refugee group that suffered persecution in Bangladesh and then migrated to West Bengal.”

Given its long and complicated historical trajectory, caste in Bengal continues to be in tussle with multiple other social identities.

Further reading:

Sekhar Bandopadhyay, ‘Caste, culture and hegemony: Social dominance in colonial Bengal’, Sage Publications, 2004

Ayan Guha, ‘Beyond conspiracy and coordinated ascendancy: Revisiting caste question in West Bengal under Left front rule’, Sage Publications, 2021

Mahitosh Mandal, ‘Dalit resistance during Bengal renaissance: Five anti-caste thinkers from colonial Bengal, India’, Caste: A global journal on social exclusion, Vol. 3, No. 1, April 2022

Anjan Ghosh, ‘Cast(e) out in West Bengal’ Seminar (508 December), 2001

Sandip Mondal, ‘Demystifying caste in Bengal’, Economic and Political Weekly, 2021

Manas Patra, ‘The visible ‘caste gaps’ amid an ‘invisible’ caste system in West Bengal, India: A study of discrimination in Bengali society’, Caste: A global journal on social exclusion, Vol. 5 No. 3, October 2024

Must Read

Buzzing Now

Mar 31: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05