Noam: Hey everyone, welcome to Wondering Jews with Mijal and Noam.

Mijal: I’m Mijal.

Noam: And I’m Noam and this podcast is our way of trying to unpack those big questions being asked by Jewish people and about the Jewish people. We don’t have it all figured out, but we’re going to try and figure some things out together, whether we make it there or not. It’s really about the process of wondering together and leaving every episode feeling like we’ve all learned something.

Mijal: Our absolute favorite part of this show is wondering with you, our special listeners, so please continue to share your questions, suggestions, feedback, whatever’s on your mind by emailing us at wonderingjews@jewishunpacked.com. Noam, so I’ve missed having you here the last two episodes.

Noam: Yeah, I know I’ve missed you too, Mijal.

Mijal: I didn’t say I missed you, I said I missed having you.

Noam: I know, I know you didn’t say that, but in my head, that’s how I translated it.

Mijal: Okay, can I just tell you, I just felt like this weird pressure, like to be funny. I don’t think I was funny, but I felt like, okay, Noam’s not here.

Noam: I like it. I’m the funny guy.

Mijal: You’re a lot of wonderful things and you’re also funny.

Noam: I didn’t know this. But here, Mijal, the truth is when when you’re funny, you’re actually very funny. You do you have good bits, you have good bits and then and you don’t see them coming. And then it’s like zing, like boom, like.

Mijal: I appreciate it. Thank you. Thank you. And then because of the accent, you’re like wondering, is she being serious or not? That’s my secret weapon. Thank you.

Noam: But that’s a good move. It’s good to be disarming. I think it’s good.

Mijal: Or intentionally awkward.

Noam: See, that’s funny. That’s funny.

Mijal: That’s how I introduce couples to each other and show some stuff. Like, let me be awkward. I’ll put you guys together.

Noam: Let me be awkward. I’m going to introduce you. You’re going to stand next to each other and talk. And now I’m going to leave. Go have fun.

Mijal: Right, make fun of me and I’ll walk away. Yeah. Thank you.

Noam: Exactly.

Mijal: Okay, so we should have an episode on matchmaking, but today we are continuing our theme of the month, which was about faith. So I had a conversation with Tanya about post Holocaust theology and faith through the lens of Purim. Then I had a conversation with Sarah Hurwitz, which spoke about faith and modernity and counter-culturalism. What are we talking about today?

Noam: Yeah. And those are two incredible people, so grateful they came on Wondering Jews. Today I wanna talk about a different topic, a topic that’s constantly on my mind and I know, know, I’m the point guard here. I’m the point guard in today’s episode. you know what that means?

Mijal: You shoot the ball in basketball?

Noam: No, that’s not what it means. I see–

Mijal: That’s not what a point guard is.

Noam: No, the point guard’s the guy or the gal dribbling the ball up the court and their job is like to pass it or to make something happen. They could shoot also. You’re going to shoot the ball a lot today. They’re going to shoot the ball.

Mijal: Okay. I got it.

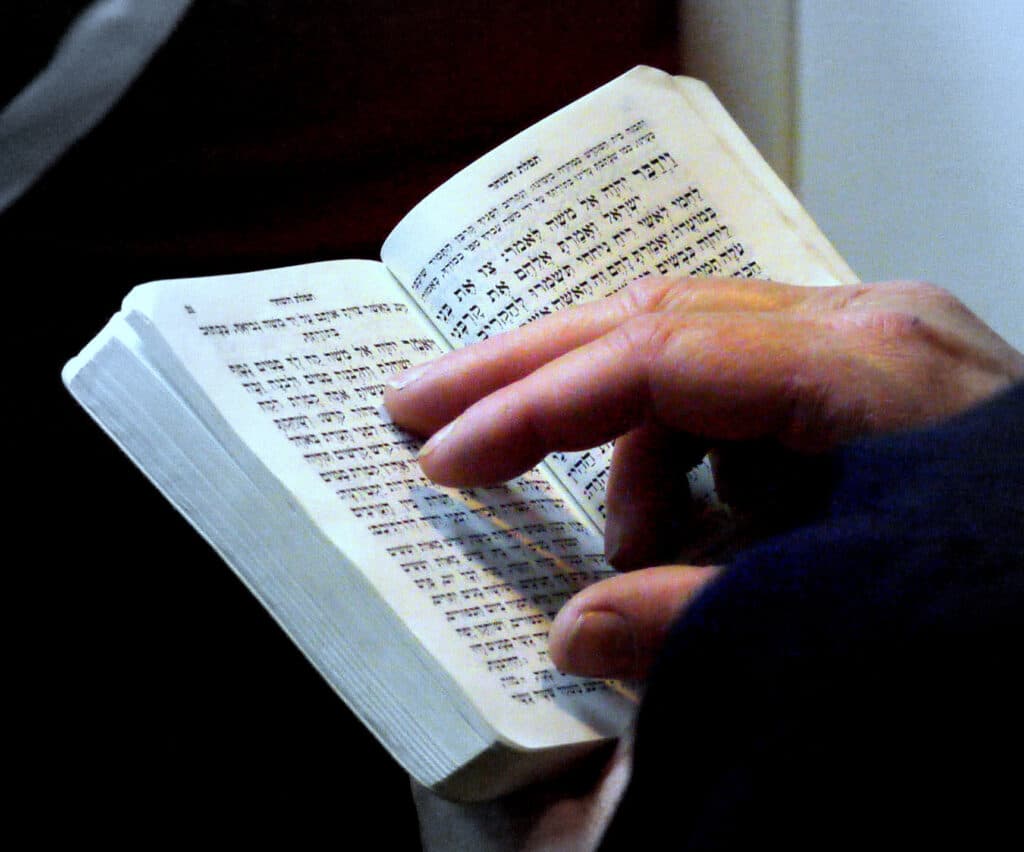

Noam: Okay, we’ll leave it at that. Here’s the topic. The topic is Jewish law and its relationship to faith. And here’s what I mean. The question is for many Jewish people, halacha, which is the term people use for Jewish law, it’s the bedrock of religious life.

As a matter of fact, there have been great scholars who have even made the argument that it is actually simply halacha, or the willingness to follow halacha that distinguishes Judaism, or rabbinic Judaism as people would call it, in the first and second centuries from in third centuries from Christianity. It is the willingness to follow halacha, as opposed to Christianity, which separated itself from halacha in the first few centuries. Something about halacha is essential for a meaningful religious connection to Judaism, to Jewish faith.

And my question to you is, is there room for faith and spirituality outside of the framework of halacha? So I want to start by framing it that way.

Mijal: I mean, yeah, I think I have a lot of friends and students and myself included can feel a connection to something transcendent in a way that is not related to Jewish law. It could be being with a group and singing together. It could be going on a meditation retreat and really connecting to a practice that gets you closer to who you think you are. For me, walking the streets of Jerusalem is a spiritual experience, and I don’t necessarily see that as fulfilling Jewish law, although arguably that could be, but that’s not why I’m doing it. So yeah, you would almost have to convince me of the opposite argument, that you need Jewish law for spirituality. Does that make sense?

Noam: It definitely makes sense. What you’re saying is that there’s spirituality outside of Jewish law all the time in life. Do you pin spirituality against religiosity then? How do you think of those two terms together?

Mijal: Ooh, this is going to get like annoyingly academic, you know, because unfortunately I studied like the category of religion.

Noam: Okay, but the way human beings talk about it on the street. Yes.

Mijal: Okay, yeah, I think colloquially religion is often having to do with organized religion and with things that can maybe be more institutional and that have more boundaries that have to do with hierarchy and people who create them. And spirituality feels colloquially to indicate something much more subjective and much more about connection, which I think is highly subjective more than just organized religion.

Noam: Okay, what I just heard is something that is externally imposed versus internally achieved. That’s what it sounded like to me, your distinction between religiosity and spirituality. A little bit, like one is more like coming from within and the other one, there’s a little bit of an external pressure to conform in some way.

Mijal: Sure, we can play with that colloquially. Don’t put me on this path like that, no. I can’t give you all my definitions. Yes, yeah. Okay, thank you for that.

Noam: Okay. Hey, all of Mijal’s academic friends, stay away. Don’t come at her for this. Do not come at her. That was on me. That was on me. So let’s start defining terms. What is halacha? What’s your definition of halacha?

Mijal: What’s your definition of halacha, Noam?

Noam: Walking with God.

Mijal: And you’re saying that because the way the word comes from like the path or walking.

Noam: Yeah, really, it’s walking with God and I think it’s been used in a different sort of way, but there’s a different word in Hebrew, which is the law, which is the din, daled yud nun-sofit, which is the law, the judgment. So there’s classes that you could take called dinim, which is learning the laws, and then there’s classes that you could take called halacha, which is, I believe, a little bit different than din, which is to figure out what it means to walk with God or to walk with the system that you have, to evolve with it, to understand it. You’re making a face at me. What’s the face?

Mijal: Because sometimes I feel like–

Noam: Yeah, push me. Push me.

Mijal: Okay, I feel like you like taking concepts that have a certain mainstream way of using them. And even though you might be okay with that, you wanna give a more less used, unique way because you think it sounds better. You think, because I think you think it sounds better to say, I follow the things. To walk with God, that I participate in this system of dry legal details that have been developed over thousands of years by rabbis and legal minds throughout the centuries. Is that a fair critique?

Noam: It’s a great critique. I mean, it might mean, Mijal, we might be friends. This might mean we’re friends. If you could call me out on that, that’s something that my friends would do. Yeah, I mean, the basic definition of halacha, it’s the evolving legal and ethical framework that governs Jewish life. It’s derived from Torah, it’s derived from rabbinic interpretation and ultimately communal practice.

So if we’re going to use definition of halacha, which means to walk with our tradition, I’m wondering for you, Mijal, in the first three hours of your morning, what halachic decisions do you make?

Mijal: So, there’s like a different set of rituals that I do that have to do with prayers and also have to do with, for example, like washing my hands a certain way and making a blessing before I allow myself to have a coffee and saying certain blessings beforehand and praying in the morning. And there’s like so many of them, from what I wear–

Noam: So it’s you say you say prayer right when you wake up, you wash your hands in a certain way. It’s just interesting to hear this. You wash your hands in a certain way. You put on certain types of clothing. You pray to God in a certain type of way. And we’re not even at 9 a.m. really.

Mijal: Yeah. And there’s other things that have to do with how I have my home set up. So like the food that comes into my house, right. It has to do with certain laws or the school that I send my kids to that’s influenced by, by the law. You know, there’s like a lot of things there that I’ve, I don’t, wouldn’t call them decisions though. They’ve become routine.

Noam: Okay, okay, fine, fair enough. So I want to think through four distinct approaches to how to think about Jewish law, to how to think about halacha through looking at these four different names: Eliezer Berkowitz, Yeshayahu Leibowitz, Mordechai Kaplan and Angela Buchdahl. So here we go.

Mijal: Are they all rabbis, Noam? Yeshayahu Leibowitz?

Noam: I don’t think he’s a rabbi.

Mijal: Okay, so three rabbis and a professor.

Noam: Yeah, and a philosopher. So Eliezer Berkovits, he’s a theologian. I think he views halacha as deeply connected to ethical concerns, and he views it as being this relationship between tradition and moral intuition. So he views halacha as divine morality in action. That’s, that’s Berkovits. He would view halacha as a there’s a bilateral relationship between man and God as opposed to a unilateral relationship.

And therefore human beings are able to have a more constructive approach to the determination of what the Jewish law, what the halacha should be. It could be the role of women in Jewish law. It could be how to think about the LGBTQIA+ community in halacha. It could be whether or not certain boundaries used to exist and don’t exist anymore. And there are lot of different ways, but basically human beings have more of a role in determining what halacha should be than simply a unilateral relationship that is from the divine to man.

Mijal: Okay, so you’re saying that one of the aspects of his thinking is that there’s something almost like co-creating Jewish law, that it’s both reflective of divine will, but also reflective of human interpretation. If I recall, I wrote a grad school paper actually contrasting and comparing John Dewey’s, John Dewey’s like a famous philosopher who wrote about education and democracy and other things in America. I compared him with, with Eliezer Berkovits–

Noam: That’s cool. That’s my version of cool.

Mijal: Yeah. Thank you very much. But if I recall, there’s one more approach and another aspect of Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits’ approach to Jewish law, it’s not only that we co-created, but that it also supposed to make us like more ethical people. It’s supposed to shape us. So it’s not just about waking up and saying a prayer, that act of saying a prayer, acknowledging that I’m alive is supposed to make me into a more grateful, more generous person.

Noam: Yes, and what he would say is that there’s a tremendous amount of precedent in the Talmud and the Torah to demonstrate that. His key texts are number one is the story of Abraham fighting with God in the story of Sodom. That’s a key text for him where Abraham is part of that story. They’re co-creators of whatever emerges. And in the Talmud, there are a number of stories he talks about, again, for a different episode.

But let’s get to the number two. Yeshayahu Leibowitz. Yeshayahu Leibowitz, incredibly provocative and controversial philosopher. I think that he is often thought about in the context of how he views the story of Zionism in Israel. But in our conversation, he has lectured at length about halacha and what he, I would say, views Jewish law as, as in, I’ll say in Hebrew because this is what he spoke about all the time, Kabbalat ol malchut shamayim, meaning the acceptance of the yoke of heaven.

And what that looks like is, it’s absolutely a unilateral relationship and specifically a non-instrumental service of God. The purpose of halacha is simply to follow what God says, not to get anything in return for it.

Mijal: Right, I would even say that just for like the everyday ritual, an approach like this one would basically say like, don’t try to find a reason to feel good about all this. The concept in Hebrew would say is like, taamei hamitzvot, like trying to figure out the reasons.

Noam: Reasons. Yeah, exactly.

Mijal: So very often people will say, keep Shabbat because you will relax and like family, right? keep like eat kosher, it’s healthy for you. Or like–

Noam: Family time. Yeah. Exactly. Perfect. Yeah. Yes. Yeah. You’re right.

Mijal: you’ll meditate. So Leibowitz would say like, I think he would go as far as to say that’s like idolatry. That’s about your human interpretation of that. And really we keep Jewish law because God is beyond us and we don’t understand God. And if God says something, I do it. And if it’s problematic, I do it as well. That’s my service to God.

Noam: Exactly. And the reason for that, the reason it’s idolatrous is when you switch the means for the ends, that becomes a problem.

Mijal: Okay, give an example. What do you mean by that now?

Noam: Exactly what you said, which is if the command is to keep Shabbat and then you say the reason I’m keeping Shabbat is because it’ll bring me family time, it’ll bring me something else, whatever the thing is, then you’re not keeping Shabbat for the ideal reason. You’re actually keeping Shabbat in order to accomplish something else.

Mijal: So it’s interesting that we can already begin to see a contrast. Rabbi Berkovits is very much thinking about making the individual better, making society better. And then like Leibovitz’s approach is so much more like God said so, so we do it. And we don’t pretend like we understand why or try to make meaning in a way that is not actually reflective of God.

Noam: Exactly.

Mijal: Which one’s your approach, Noam?

Noam: Well, none of them so far. Actually, that’s a lie. And sometimes it’s Liebowitz, sometimes it’s Berkovitz.

Mijal: That’s a bit of a cop out.

Noam: I am a bit of a cop out. I’ll tell you, I’ll give you my thoughts, I’ll give you my thoughts, I, sorry.

Mijal: I wasn’t going to say that, but that’s a cop out there. Just kidding.

Noam: Audience, this is the way I process information. I need to share different ideas. We’re gonna hear the ideas, and then I am going to tell you the way I think about it. But I need to go through the process. And so trust the process. Let’s go through it, let’s go through it.

Okay, then you have a third thinker, Mordechai Kaplan, who is…

Mijal: Okay, so sorry, sorry I interrupted. These are all by the way, like modern, 20th century rabbis, all of them.

Noam: 20th century. Yeah. He founded Reconstructionism. He was actually a rabbi. This is a great stat.

Mijal: Lincoln Square Synagogue. Okay, KJ? Wait, no. Shoot, I got it wrong.

Noam: No, I think it was Jewish Center. It was Jewish Center

Mijal: Okay. Some Upper West Side shul.

Noam: And Kehilat Jeshurun, and KJ, on the Upper East Side. Upper West Side and the Upper East Side, like fancy shmancy synagogues.

Mijal: Right, Orthodox.

Noam: Yeah. Orthodox. Exactly. So it’s interesting. And he was a professor at JTS. And just really, really influential figure, he came up with Reconstructionism and he viewed Halacha, Jewish law, as part of the society or the civilization or the culture of Judaism and therefore it matters. It matters in the sense that it is descriptive of the Jewish experience and it’s part of it, but not that it’s binding in some way that is legal formally and not binding in some way that is from God, that God’s divinely telling you to do this.

Mijal: Right, would say maybe, and I’m saying this a little bit simplistically, ritual is sociological significant, right? Not necessarily theologically.

So a different way of saying this, like you can study people like Durkheim. He was one of the great founders of the way that we think about religion in modern sociology. And he wrote about ritual and what it does to society, even religious ritual. So he would look at it, at ritual, and it wasn’t necessarily well, this is what God says. It was, this is what it does to a society. It keeps it together and cohesive if it has certain rights, you know, and rituals as a civilization.

Noam: Yes, that is brilliantly said and I think it is because it’s very complicated. People would call Kaplan’s approach to Jewish law atheistic. I think that it–

Mijal: I feel like it’s not an atheist. It’s not an atheist way to approach Jewish law, but it is a way to approach Jewish law that is independent of God.

Noam: right, exactly, exactly.

Mijal: I’m not sure though. Like, I think it’s just independent of God. Like it’s like we can talk about God separately, but Jewish law in this case, it’s like, it’s a part of like what it means to have a civilization.

Noam: Exactly. And then what about Rabbi Angela Buchdahll? She is a prominent Reform Rabbi. But what would you say her approach is to Halacha?

Mijal: Hmm. I’ll call her Angela. She’s a friend and such a wonderful Jewish leader. I don’t know if I’ve ever spoken with Angela about like her particular approach, but I’m going to, maybe I’ll just express what I think is like a mainstream Reform Jewish approach to Jewish law. And we can check later with her if she would associate with it.

But the way that I have, the articulation that I’ve heard, in terms of the Reform movement’s approach towards Jewish law is that Jewish law is something that can be chosen, but shouldn’t be imposed. The language that I’ve heard is like, informed choice.

It’s a little bit complicated because the Reform movement itself actually has a whole history. I think at the beginning of its inception, there was a bit of like, antipathy to Jewish law, the early leaders in the Reform movement view Jewish law as something antiquated and something perhaps even to, yes, to reject.

In modern times, Reform rabbis, theologians and thinkers have, it’s almost like they’ve said, we have, like, this buffet of Jewish practices. And what’s really important is for individuals to be exposed to them. But then Reform theology actually places great value in agency, an individual agency.

So it’s almost like part of what it means to be a mature Jew. Theologian Eugene Borowitz, I think he’s the one who’s also written about this. Part of what it means to be a mature Jew is to be able to look at this ritual and to decide, to make choices. So it’s not binding, right?

Noam: Okay, fine. So we have four different approaches and I’m not trying to equate them, make them equivalent to each other. I just want to be descriptive right now. There’s the concept of halacha and there’s a concept of, how do you deal with or internalize or utilize halacha in your very life?

So what I want to now figure out is, is halacha critical to the Jewish experience? Meaning, do you think, do we think that living a life of halacha, living a life of Jewish law is critical to Jewish continuity? Or is it okay if we kind of make it something that is cultural, something that is civilizational?

And I’ll tell you where I stand on that. Okay? So, because you asked me what my opinion is and you’re calling me a cop-out person, which I hear. No, no, no, no, no, because I do typically like to just show different perspectives. I want people to kind of like…

Mijal: Sorry about that.

Noam: internalize them on their own. And I’m very conscientious about how presenters often subtly tell people how to think about things. And I get nervous about that, or what to think about things. So that’s my issue. I get nervous about that.

But here’s something that Rabbi Sacks said. And I’m going to butcher it because it’s not said as nearly as eloquently as he. He says that culture is not binding, halacha is. And if there’s going to be something that’s going to make the Jewish life continue 50 years from now, 100 years from now, 200 years from now, it’s a life of halacha. It’s a life of saying, it is demanded of me to continue this. And then I feel that obligation. I feel that obligation.

So I do think that I get nervous that a life in the United States of America, it’s hard for me to see Jewish life strongly continuing in the United States of America 30 years from now, 50 years from now without halacha at its core.

So I’m wondering, this is what the name of the podcast is, is, what does a strongly held Jewish life look like 50 years from now in the United States of America? That is, and what people thought about Orthodox Judaism in the early 20th century was that it would disappear in the United States of America, and somehow it has not disappeared, it’s had some sort of resurgence.

Whereas, and this is the distinction of making in Israel versus the United States of America. In Israel, I think there’s a phenomenon that I cannot point to in some statistical sort of way, but you will find Orthodox Jews who move to Israel, I’m using this as a metaphor, wearing a kippah, and then when they move to Israel, they take it off. Why? Because you don’t need to externally come across as a halachic Jew, someone who follows halacha, because the culture in Israel is Jewish, because the food you eat is Jewish, because the calendar is Jewish, because your life is Jewish.

And there were great Zionist thinkers who said, listen, the whole purpose of halacha was to keep us integrated together. But now that if there’s a new world and a new way of thinking and the Jewish state, then the purpose of halacha is not to govern you. But the purpose of halacha is to influence you. And those are two very different ways to think about halacha.

And I’m wondering if in Israel that’s easier to do because the culture, because the calendar, because the society, because the whole air around you is Jewish versus the United States of America and other parts of the world. It’s not Jewish. It’s not what it is. It’s other wonderful things. But then in order to have your identity in order to really be Jewish, you do halacha, right? You do Jewish things, which is following the first three hours of Mijal’s day.

Mijal: I don’t think anyone should follow the first three hours of my day.

I think you’re suggesting that halacha is almost like an exilic mechanism to kind of keep Jews Jewish. By exilic, I mean something that is like almost like diasporic, which means that when you don’t have your own public square, on your own country with your own calendar and everything, you kind of need to create like a parallel set of laws in whatever country you’re in.

Noam: And I’m not the one that came up with this. The Talmud says this. The Talmud says when the temples were destroyed, all we have is… Which is what?

Mijal: Right. All God’s presence had is the four cubits of Jewish law, which means what? Let’s unpack that.

Noam: Right. I have no idea what that means. I really don’t. But I think that it’s a little bit aligned with what you’re saying, that there’s something deeply Jewish about living in a world. The temples represent something, meaning the temples represent Jewish sovereignty, Jewish autonomy, Jewish service, like a deep cleaving, a deep connection, relationship with God. And then when you don’t have that, then the way to arrive at that is through halacha.

Mijal: So let me ask you then, how does this theory, the way that you’re thinking about halacha, different interpretations, differences between America and Israel, how does this relate to faith?

Noam: Because I think the question is, what is faith? Is faith, like Yeshayahu Leibowitz says this line about faith, it’s a very profound line and very difficult line. He says, is the yoke of heaven on you, is the observance of Jewish law. One approach to faith, what does it mean to believe, to have faith in what? What am I looking at? What’s around me?

So he says, the expression of faith is doing Judaism. That’s his definition of faith, is doing Judaism. Not of something in my head, but something in my hands and something in my feet. And it’s the action of Judaism. It’s actionizing Judaism. Activating Judaism is belief, is faith.

Mijal: Okay. Maybe we can say he’s saying, don’t think so much about God or faith or theology. You want to be a person of Emunah, which faith is not the perfect translation, but a person of loosely translated, yeah, faithfulness, follow the word of God and, and don’t ask any questions.

Noam: Faithfulness. Exactly. Exactly.

Mijal: So where does that leave us? Do you like that?

Noam: I struggle with it. Again, today’s episode is I’m sharing with you things that I’m struggling with as it relates to halacha. I run a Friday night service and you run a whole synagogue experience in general. I want people to connect, to connect to something, to connect to something. And I think what halacha does often is it allows you, it gives you the framework to do that.

But for some people, it’s limiting and you don’t get to really express your faith. You don’t really get to express your faithfulness, your connection, your cleaving. You don’t get to do that. And so I struggle with figuring out when to live that Leibowitz approach, which is, listen, the reality is that it’s time to say mincha, it’s time to say the afternoon service, whether you get something out of it or not. And there’s something liberating about that. There’s something deeply liberating about that.

And then on the other hand, if I want people to just connect to God and it’s at this point in time in the prayer service, it’s not this prayer, it’s another prayer. Still say that prayer that’ll bring you to God right now, right? Or if it’s like, you you’re supposed to say every single line, don’t say every single line. Just say a few sentences, a few lines that speak to you and close your eyes. And that’s okay too. Or sing or hum. And that’s okay too. But it’s not, you’re not fulfilling every line that you’re technically supposed to say.

So it’s this relationship to halacha that’s both having halacha influence me and also having halacha at certain points in time governing me.

Mijal: Okay, interesting. I think of like, spirituality, Jewish spirituality and then Jewish law almost as two different languages that we have that I think are good to learn, you know, and to use. And sometimes they can like harmonize, you know, with each other. And sometimes they have to be separate from each other. But I don’t feel, it’s interesting. I don’t feel bad about that. I don’t feel bad about the fact that sometimes Jewish law will feel disconnected from spirituality. Do you get what I’m saying?

Noam: I totally get what saying. I’m just wondering when do those collide and when do they stay separate from each other?

Mijal: Well, it’s a very personal question, right? So I mean, there’s plenty of ritual that I feel super connected to. And when I do it, there’s like something very powerful happening. And there’s also some ritual that I feel pretty apathetic about. And there’s some ritual that I really can’t stand, I’m being honest here. But that but you see, like I am actually like, I don’t feel torn. I think that’s OK. It’s my people’s code of laws. It’s developed over centuries. There’s a lot of divine will that I will never understand. And also a lot of legal code that developed in different ways for different reasons. And, yeah, it’s interesting. It’s interesting, I think what I hear from you is that you’re thinking a lot about the disconnect and I’m kind of okay with it.

Noam: Right, you’re much, you’re comfortable with it and I’m trying to figure out my place in it. And I think at different points in time, the reason my cop-out answer from before is because I could go through different years of my life where I’ve been much more thinking through the prism of Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits, or much more through the prism of Yeshayahu Leibowitz, or much more through the prism of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks or Mordechai Kaplan even. Because each of them, no matter what, they still want to make sure that halacha in whatever form is part of your life.

And I’ve been blessed in many ways to have halacha as part of my life. I’ve seen my own religious sense of self change over time. It could change by the day, it could change by the month. But no matter what, has, having that in my life has allowed me to have a very close relationship with God.

Mijal: Noam, what are your big takeaways from this?

Noam: My big takeaways, I think it’s really important for people to, for me, to, when you hear a term, this is true for so many terms, like Zionism or faith or faithfulness or halacha, to know that these terms, when people hear these terms, they hear something that is different from the other person. And that’s like a really interesting thing when you think about language and communication, that the same word could mean something very different to different people and therefore their reaction to it could be very different. That’s why I like personally going through the exercise of thinking of how each of these great theologians and rabbis have viewed the term halacha. What about you?

Mijal: Yeah, I think it’s really interesting to think through, like you said, concepts that we use often and the way that they mean different things. And I think I’m finding it interesting just now to hear from you, the gap between feeling spiritually connected and between just following a practice that we’re obligated towards and what this gap says about our Jewish lives. I think that’s a big question there.

Noam: Yep, so I guess we’ll end with these questions and we’ll continue with our last episode on faith next week.

Mijal: Awesome. Okay, Noam, I’ll see you soon.