As happens several times each week, something new has appeared on the website of the nearly-dead and never-changing website of the Interpreter Foundation. It’s a new review essay in Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship: “Wonder No More: A Review of Into Arabia,” written by :

Review of Warren P. Aston, Godfrey J. Ellis, and Neal Rappleye, Into Arabia: Anchoring Nephi’s Account in the Real World (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2024). 298 pages. $44.99 (hardback), $39.99 (paperback).

Abstract: Into Arabia is a collected reprint of six articles. The first chapter reprints an article that first appeared in BYU Studies. The other five appeared in Interpreter. Both BYU Studies and Interpreter are peer-reviewed academic journals, which means that all these articles were examined and reviewed prior to publication. Thus, my review is more of a synopsis of the importance of each chapter rather than a detailed critique.

This is a book that I wish I had written. You can read more about Warren P. Aston, Godfrey J. Ellis, and Neal Rappleye, Into Arabia: Anchoring Nephi’s Account in the Real World here. And you can order it here.

Incidentally, today marks the six-hundred-and-sixty-first (661st) consecutive Friday of publication for Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship since its founding 662.5 weeks ago. At least one article has appeared each Friday, without interruption, since we launched the journal back in August of 2012, and sometimes two or even three articles have been published on the same Friday. (Along with the blog entries and reprints and etc. that appear on other days of the week.) It seems undeniably obvious — doesn’t it? — that the Interpreter Foundation is on its deathbed, as hath long been confidently prophesied. However, I begin to despair of ever being able to help some of Interpreter’s more unhinged critics to understand this. They confuse our Thursday reprints with our Friday journal articles, imagine that we’re trying to substitute reprints for new articles, arbitrarily decide that review essays don’t count as articles, accuse me (on the basis of their own willful confusion and misunderstanding) of attempting to deceive them, and, just generally, remind me of one of the famous corollaries to Murphy’s Law: “It’s impossible to make anything foolproof, because fools are so ingenious.”

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

So far as I can recall, I have never been a young-earth creationist. Not even when I was a child. (I played with dinosaurs and I loved going to the La Brea Tar Pits and to natural history museums in Los Angeles and elsewhere where I could learn about prehistoric animals. I always knew that they lived millions of years before the present.)

I’ve also never denied the reality of organic evolution, for which the evidence seems to me overwhelming. Barring some inconceivable scientific upheaval, I don’t believe that a religious viewpoint that altogether rejects the idea of substantial biological change over time or that denies the evidence for a very old Earth can be intellectually sustained. One of the early articles that we published in Interpreter was Gregory L. Smith’s ““Endless Forms Most Beautiful”: The uses and abuses of evolutionary biology in six works.” Since then, I myself have written affirmatively about an important book reflecting on evolution (“How Can We Make Sense of Evolution?: A Latter-day Saint Perspective”) and have conducted two friendly video interviews with Latter-day Saint scholars for the Interpreter Foundation that plainly presuppose belief in evolutionary theory. (See “Interviews with Ben Spackman and Samuel T. Wilkinson.”)

That said, my views on the subject are not firmly settled. Nor am I in any particular hurry to settle them; in most regards, I don’t consider the issue to be of primary importance.

One of the things that I read on the way over to Kaua’i on Wednesday was

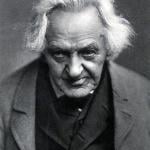

Let it be acknowledged right up front that Neil Thomas is not an evolutionary biologist. He is, rather, a Reader Emeritus in the German section of the School of European Languages and Literatures at the University of Durham, England. Trained the universities of Oxford, Munich, and Cardiff, his teaching at Durham covered a broad spectrum of subjects, including Germanic philology, medieval literature, the literature and philosophy of the Enlightenment, and modern German history and literature. He sometimes focused on the propagandist use of the German language employed both by the Nazis and by the functionaries of the old German Democratic Republic. Notably, too, he was a longtime member of the British Rationalist Association and, even now, he describes himself as committed to “no revealed religion.”

Although not a biologist, Thomas has plainly read widely and deeply on the subject of evolutionary thought. He is a first-class intellectual historian, and I found his book impressively learned and deeply interesting. I recommend it to anybody who is really concerned with the topic of the origin and development of Darwinism and, yes, in the leaps of logic and the evidentiary gaps that, Thomas argues, continue to exist in it and to cast grave doubt upon it. I will almost certainly be drawing upon Taking Leave of Darwin for future blog entries here.

Among the major problems still faced by evolutionary theory is the question of the origin of terrestrial life. It is one thing, say, for the Darwinian mechanism of natural selection to work on existing organisms, but where and how did organic life originate in the first place? Charles Darwin couldn’t answer that question, and neither can the science of our day. Certainly not definitively, though there has been no shortage of effort devoted to it and although there has been no lack of hypotheses.

My attention was caught this morning by an article on the CNN website, “Iguanas floated 5,000 miles from North America to Fiji on vegetation rafts, new study finds.” Genetic evidence suggests that the ancestors of today’s Fijian iguanas came originally from what is today the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico, arriving in Fiji between 34 million and 30 million years ago. The Fijian archipelago is a volcanic formation that was originally barren of either botanical or zoological life. In this regard as in others, of course, Hawaii is a parallel case. The Hawaiian Islands originally emerged from the sea as sterile volcanic rock. How did flora and fauna arrive here?

But the largest parallel, obviously, is Earth itself. How did life arise on our planet? The problem of the origin of terrestrial life has proven so intractable, thus far — although, by and large, devotees of abiogenesis continue to hold to the promissory faith that a solution to that problem will shortly be found — that some over recent decades have proposed that the explanation lies in the notion of panspermia (from ancient Greek πᾶν [pan] ‘all‘ and σπέρμα [sperma] ‘seed‘). This idea is the hypothesis that life exists throughout the universe, and that it is distributed by space dust, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, and/or planetoids, and even perhaps by alien spacecraft carrying unintended contamination by microorganisms. In fact, some have gone so far as to suggest “directed panspermia,” which holds that the seeding of Earth was deliberately undertaken by advanced extraterrestrial beings of some sort. (Given my own religious views, I’m open to the possibility of something like that being actually true.)

But the theory that life did not originate on Earth, having instead evolved somewhere else and having thereafter seeded life as we know it, goes no distance at all toward solving the problem of life’s origin. It merely kicks that problem down the road.

Posted from Poʻipū, Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi