Mijal: Hey everyone. Welcome to wandering juice with Mijal and Noam. I’m Mijal and this week I’m once again without Noam, but keeping a seat warm with a very special guest today. This show is our way of trying to unpack big questions being asked by Jews and about the Jews, working through the process together and whether we get to full answers or not, at the very least we want to leave every episode feeling like we’ve learned something together and had some fun.

As we say each week, our absolute favorite part of this show is wondering with you, our very special listeners. So please continue to share your thoughts, suggestions, feedbacks, whatever is on your mind by emailing us at our new and improved email address, wanderingjews@unpacked.media. That’s wanderingjews@unpacked.media. We are incredibly grateful for your support. And I say this like very, very genuinely getting emails on a weekly basis, it really means the world. So please keep doing it.

So getting right into today’s topic, we are right now in the month in which we chose to talk about faith. And today we’re going to try to talk about faith in a bit of like an expansive way, trying to really figure out what are different definitions, different approaches. Can we speak about faith as a practice? Can we speak about faith, not only in terms of faith in God, but in other things. And I just like to say that I couldn’t think of a better person, guest, to bring in to discuss this with me than my very good friend Sarah Hurwitz. I’m going to just say Sarah a little bit. I don’t know if you remember when we first met before I asked you to introduce yourself. Do you remember our first meeting?

Sara: I don’t,I feel like I’ve known you forever.

Mijal: Have you? I think it was COVID times. I taught a class over Zoom when I was at Hartman on Jews and race and America and things like that. And you were in that class. And I remember that I was very nervous because you were in that class.

Sarah: I think it’s hilarious that you were nervous because of me, but that’s touching. That’s very sweet.

Mijal: Of course I was nervous because of you, which actually leads me to ask you to introduce yourself. If you can just tell us three career highlights that you’d like to share as a way to introduce yourself.

Sarah: Yeah. It’s so funny because I’m nervous being with you because you know all the Torah and I still feel like I’m such a beginner, but that’s fine. We can be nervous. It’s great.

So my name is Sarah Hurwitz. Career highlights. See, I was a head speech writer for First Lady Michelle Obama in the White House during the Obama administration. And then I left there and I wrote a book about Judaism, as one obviously does when they leave the White House.

And then I am, during COVID, I trained to become a hospital chaplain, which I now just do totally on a volunteer basis. And I’m just finished my second book. So those are some career things.

Mijal: Amazing. Okay. So much. Well, first of all, just going through them, your first book Here All Along, I just want to say that I have bought so many copies. I meet a lot of people who, especially after October 7th, tell me that they want to approach Judaism either for the first time or for the first time as adults. And your book has been such a source of inspiration because people really take it and they read it and they come back to me and they tell me, wow, this was the book I was looking for.

So first of all, just thank you so much for writing that one. I would say, how would you introduce it for someone who hasn’t read the book? What do you say the book is about?

Sarah: So basically, I wrote this book because it was the book I was looking for, because I grew up with very little Jewish background. I randomly wound up taking an Intro to Judaism class at the age of 36 after a breakup when I was looking to leave my apartment. And I was just blown away by what I found. And I just thought, wait, I’m sorry. I went to Hebrew school, my parents dragged me to the synagogue twice a year, like good Jewish parents. And, you know, we did the Seder. And if you grow up like I did, you think that Judaism is for…It’s basically three boring holidays and maybe a fun party at Hanukkah and like that’s the Judaism. And also knowing how to phonetically pronounce Hebrew for your bar or bat mitzvah. And so I just thought like, why would anyone bother with this? You know, this is sort of a childish, obsolete, silly religion. I’m going to go find meaning elsewhere.

And when I actually took a class as a big girl, as a grownup, and started studying Jewish texts, I just thought like, you’ve got to be kidding. Where has this been all my life? Like I saw precisely none of this in my childhood Judaism, again, because I was a child. So I really couldn’t see the sophisticated, transformational, radical, countercultural texts that are part of our tradition. And so I started learning and like there were lots of great intro, how-to, nuts and bolts books, and there were lots of excruciatingly painful academic books. But there was really nothing that was, yes, cover the basics, but more importantly, delve deep into the why to, right? Like what is the most transformational, radical, countercultural, amazing wisdom that our tradition offers for us today?

And you’re right, my target audience really was folks who kind of grew up like me or folks who were coming to the tradition for the first time. But I have been shocked by the number of very observant Jews who’ve said to me, this book is for me. I don’t necessarily agree with everything you say. I don’t practice like you do. But I saw the 500 end notes at the end of this book. You did your homework. And you love this tradition as much as I do.

Some people have said to me like, you help me fall in love with the tradition again. I just thought like, I never, that I never would have thought of. And that’s been really, it’s been really fun to see.

Mijal: Yeah, I actually met somebody who grew up in an Orthodox community, then they ended up leaving that community, it wasn’t for them. And now re-exploring what kind of Judaism they want to live. And they read your book and they told me that they really needed that. They needed an invitation to kind of step into it again and to ask big questions. And your book is not like narrowly prescriptive. I think it’s an invitation to come and explore and ask big questions.

Okay, but the next book that you have coming out, it’s a totally different topic.

Sarah: Yeah. my first book, was like, I found this tradition. I’ve fallen in love with it. Yay. I’m going to write about it. So happy. And then during COVID, I was like, why exactly did I see precisely none of our tradition in the Judaism I had growing up? In fact, I began to realize the Judaism I had growing up was highly edited in a very strange way. And so I started going back through history.

And you know, I made this kind of both heartbreaking and also inspiring and affirming discovering that, you know, when Jews, and this is very Ashkenormative, I apologize for this, this is very European, but just give me permission.

Mijal: I give you permission, go for it. Yeah.

Sarah: Before modern times, Jews kind of lived in very isolated, insulated Jewish communities. You were not a, a French person of the Jewish religion, you were just like a Jew, right? And then once Jews were offered citizenship in Europe, as was part of the transition to modernity, they suddenly had to figure out, wait, can you actually be both Jews and Frenchmen, both Jews and Germans? And so what one branch of the Jewish world did is they said, yes, we can. Reform Judaism such that we can be Germans of the Mosaic persuasion, right? We can be Frenchmen of the Jewish faith.

So Judaism, which really, it’s not a religion, it’s not an ethnicity, it’s not a race. Judaism actually, Jewishness precedes all of those categories. Those are modern categories. We are whatever the Hittites or the Ammonites or the Edomites or those Biblical people. Like that’s what we are. So I don’t know, tribe, family, civilization, peoplehood, call it what you want. That’s what we are. But in that transition to modernity, as we were trying to become citizens of Europe, we kind of made Judaism into a Christian style religion. And we said, no, no, no, we’re not Jews. We are…Frenchmen of the Jewish faith, right? We’re Germans of the Mosaic persuasion?

And so, you know, there was this kind of, this is a way overstatement, so I just want to say this lightly, but it was kind of like we jammed a Protestant cookie cutter into Judaism and got rid of everything that didn’t fit. And thank God, you know, thank God we did because that allowed Judaism to transition into modernity. It allowed Jews to be citizens of their countries. You know, it really was a very effective thing that worked quite well, I think, for a couple hundred years.

And some Jews didn’t do that, right? There was a reaction to that reforming movement and it came to be called Orthodoxy that said, no, we resist change. We don’t like any change at all. We’re really gonna preserve this. And then there was a reaction to both of those denominations with the Conservative movement.

And those were all incredible gifts, Those brought us into the modern world. So I’m so grateful to our ancestors for doing that. But you know, I sort of look at this today and I just realized like these main denominations were all just reactions to a certain time and place which made so much sense in that time and place and I almost have this like weird hypothetical in my mind that like what if we could go back to the year 1800 and you know imagine things differently without this you know European Christianizing atmosphere where we’re kind of so embarrassed by our Jewishness where we kind of think that the Jewishness is kind of disgusting.

Anything after the Bible is gross. It’s just this esoteric nonsense. We don’t respect that. It’s really the Bible that’s great. It’s the prophets that are great. It’s, you know, ethics is really what Judaism is. I understand that. And that really was so helpful for transitioning to the modern world.

But now I wonder, you know, we lost so much. We lost the idea of study as a form of spiritual practice. You know, I actually think that studying Jewish texts is the most important form of spiritual practice.

But think if you ask the average American Jew, they’ll be like, no, no, Jewish spiritual practice is reciting prayers in unison in a synagogue and I find it boring. And that breaks my heart.

Mijal: So you’re saying, there was a bargain, right? At a certain moment in history, like many times, Jews were minorities who had to contend with new nation states and new notions of citizenship. And in the bargain, we achieved certain acceptance.

Sarah: great way to put it. Yeah.

Mijal: But we also had to denude, is that a word? Give up certain core parts of our Judaism. And one of the examples that you’re given is that you’re saying something like maybe a very Protestant form of spirituality that thinks of prayer and not study, let’s say, as an avenue towards that.

Sarah: Exactly, exactly. Not to say, of course, communal prayer is a very important, centrally important Jewish tradition. Of course it is. But, you know we lost study. We lost a lot of primal earth and nature based traditions that were considered kind of barbaric or primitive in Europe. know, you even saw people giving up blowing on the shofar, the ram’s horn, which we do at Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, because it was sort of primitive.

You know, there was a there’s a traditional Jewish practice of when either when you learn that a loved one has died or at the loved one’s funeral, you tear your clothing. It’s called kriya. And it is this very primal moment of just expressing how torn you are, how torn your world is. It’s really, it’s very powerful practice. But again, primitive, barbaric, don’t…

Mijal: Sarah, let me ask you, orthodoxy still does all these things, right? Orthodoxy still does the tearing things, lots of the primal stuff, you know, all of those things, the study.

Sarah: Am I making it argument for orthodoxy?

Mijal: I don’t know, I didn’t say that, you said that, you know what I mean?

Mijal: or you want them to be Sephardic.

Sarah: No. This is the thing that’s so funny. That’s actually the first reaction I get when I say, when I sort of talk about these costs, they say, you want everyone to be orthodox? A, I’m not orthodox. Actually, I don’t want anyone to be anybody. That breaks my heart because it’s sort of a sign of how deeply entrenched and embedded we are as this very narrow way of thinking. okay. You’re saying you don’t want this progressive kind of Judaism. Thus you must want this Orthodox kind. not that you must want conservative. These are all great things. These denominations are wonderful and work for many people, but they’re all modern inventions. And I think, they also, are many people for whom then maybe they’re not quite working.

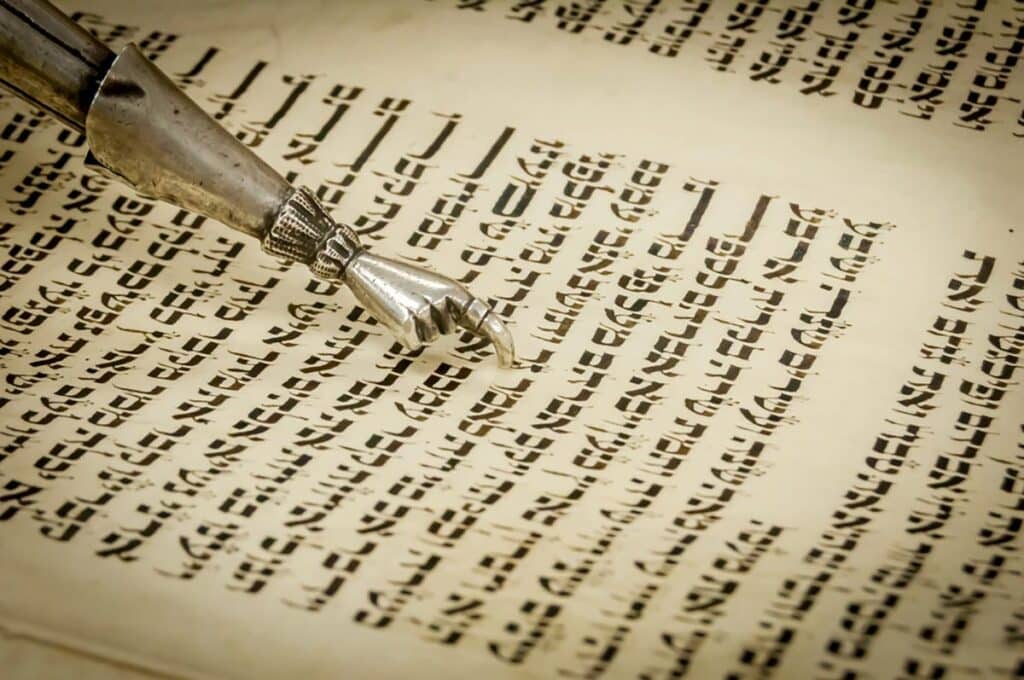

And the fact that we think about Jewishness as being broken down into certain categories of how ritually halachically observant are you? That’s your Judaism. Whereas I just want to step back and say, if you want to ask, what do I want people to do? I want people to learn. Amos Oz and Fania Oz-Salzberger, beautiful authors, historian and Israeli author. They wrote a book called Jews and Words. And at one point they said, Ours is not a bloodline, it’s a text line. And I thought like, that’s it. Like tribes, civilization, great. We’re a people who are based on a text line.

And I want people to become familiar with that text line. I want them to understand all of the 2,500 years of texts after the Bible. You know, Jews like me growing up, you look at the Torah and you’re like, this is insane and sexist and they seem to like slavery. Like, whoa, not good. And you think that’s the Judaism. That is like looking at an original draft of the Constitution and saying, America allows slavery, it doesn’t let women vote, this this Constitution is appalling.

Mijal: Well, you do know some people still have that reaction.

Sarah: They do, so that is true. I would point them to 250 years of court cases. And similar with Jewish tradition, I would point them to 2,500 years of Jews reinterpreting, reimagining, re-understanding their text. And I think we have lost that post biblical textual tradition, which has some of the most radical, inspiring, affirming, relevant, desperately needed counterculturalism that we need right at this moment. And we kind of have downplayed it. And by we, I don’t mean everyone. I’m just saying many parts of the Jewish world. So I want us to reclaim that.

Do whatever you want with it. Practice however you want. It is none of my business. There’s no one right Jew. I think the Jewish world is like a body, right? To say, the heart’s more important than the lungs or the stomach is more important than the spleen. Like, what are you talking about? Every organ has a critical function. and they all need to be healthy for the body to be healthy. And that’s how I think of the Jewish world. We need a healthy, secular Israeli Judaism, a healthy Haredi Judaism, a healthy Reform Judaism, a healthy Earth-based feminist Judaism. I think all of them contribute tremendously.

Mijal: Yeah. I mean, in many ways what you’re saying, like pointing to text in some ways, text and Jewish learning are really helpful for a certain like pluralistic approach because text is available to everybody. Interestingly, I said it kind of like flippantly, you want to return to like a pre-modern, we can call it, you know, a Sephardic tradition on Judaism situation.

But I think for, I’ll just draw a contrast. I think for me, I agree with your critique of denominational Judaism as potentially like too narrow for who we are and who we want to be. I still think I’m on the side of like a tribal family Jewish peoplehood. And there could be real tensions that we could speak about between a text based approach and a family based approach.

Sarah: But here’s the thing, it’s a family that’s sort of based on a text line. Do you know I mean? Like, you know, if you just say it’s a family-based approach as if it has no content, no history, no substance, I don’t think that’s true, right? It’s both pieces. And I actually strongly feel the importance of that family peoplehood tribal approach, which again, that too was lost.

When we become a Christian style religion, then it’s just like, we believe the same things. So I have no loyalty to people who believe the same things as me, whereas I do have a loyalty to my family. So I think that’s where we lost that as well. And by say we, again, I’m talking about a time, place, location. What you’re talking about, other parts of the Jewish world didn’t lose that. There’s something different going on there, which I think is really powerful. And I’m very inspired by that kind of Judaism.

Mijal: Yeah. So let’s talk a little bit about faith. So beforehand, Sarah, we were chatting before the episode and you suggested something to me that was really intriguing. One way to think about Jewish faith is to think about Jewish faith as a certain counter-culturalism, a certain kind of like push and impulse for Jews that in any society that we are in, we do not drink the moral kool-aid of that society. And that we always tell ourselves that there’s going to be something inside our tradition, the texts that we inherited, the people who we are, that should lead us to push back in some ways.

That’s a little bit what I, you know, in our conversation we were talking about, which made me think a lot about one very early midrash, one very early rabbinic teaching that describes Abram, like Abraham before he became Abraham. The father of monotheism of the Jewish people. And he is called Avraham Avri, which in modern terms, we would think it’s describing, it’s an adjective, Abraham the Hebrew, right? From the Hebrew people speaking Hebrew, whatever it is.

But the rabbis in the Talmud actually ask why is he called this? You know, before there is a Hebrew people. And one of the opinions given is that every Hebrew is not describing a group. It’s actually describing the word me’ever, being across. And there have been in Texas, the entire world was on one side and Abraham was, and I’m gonna add Sarah, you know what I mean? Was on the other side of this, which tells you something very powerful that what characterized the genesis of our people according to this text, wasn’t necessarily, the rabbis aren’t saying this, but I’m going to say this to make a point. It wasn’t like faith in the one God. It was faith in the one God, but it was the ability to stand across the entire world and to say, it’s not about the majority. There’s something about faith that allows me to stand separately and to push back against the world.

Sarah: I love that and I’ll even build on that. I mean, this was the call at Sinai. You know, like if you’re reading the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, what Christians call the Old Testament, you know, God rescues Jews from Egypt. They then assemble around the base of Mount Sinai and God sort of gives them the Torah. God gives them all these laws. And it’s like, you can sift through all these laws, commandments. It’s like, are we doing here? Like, what is this?

I think that one way of thinking about what the Torah says, it’s basically a demand that Jews build a society that is the exact opposite of Egypt. Like, all of those ancient societies that practiced child sacrifice, that would rip a leg off a live animal and eat it, so many of these laws that God says the Israelites are like, don’t be like them. Do not be like Egyptians, do not be like Mesopotamians. They worship kings and gods and emperors.

I am telling you to worship the poor, the stranger, the widow, the orphan. That’s who you care about. That’s who I love, that’s who you love. It is a radical countercultural kind of document. So I think that call to be different. And I think what’s so interesting about the Torah is like, God in the Torah is constantly telling the Israelites to like, don’t believe in other gods.

But there’s just not a lot of God being like, you need to believe in me and have faith in me in your heart and take me into your heart and believe in me. it’s sort of almost not necessary. It’s like God’s just there. There’s no like need for the proof text in the Torah. God’s just kind of there. And the main concern is like, please don’t worship these other gods who are kind of problematic and don’t worship idols.

I do think it’s like, there’s some way of understanding if the God thing is problematic for you, there’s some way of understanding faith in the Jewish context as faith in this Jewish project, as faith in this thousands year old civilization that has throughout its history been this countercultural radical force very often, sometimes not, but most of the time, and has survived and thrived and basically made just shockingly amazing contributions and disproportionate contributions to the world. Can you look at it that way?

You know, I find it utterly enraging when people define God as this, is a being in the sky who controls everything. That’s God. And then they smugly proclaim that they could never believe in such a thing, but isn’t it wonderful when people believe in it because they need that to feel safe in the world. I’m so happy for them. Like, I find that so condescending. I find it so arrogant. I don’t believe in that kind of God. And I think, you you’ve studied much more Jewish tradition than I have, but from the Jewish tradition I have, it seems that actually our tradition also does not put forth a childish, simplistic kind of God. In fact, most religious traditions actually have a lot of sophisticated, complex, contradictory ideas. And for people to just be so condescending about these deep, vast old religious traditions makes me really frustrated. So I really want to push back against that as God, and I love this idea of making it little broader and more complex.

Mijal: Well, let me ask you actually, you worked in the White House, you’ve been like in what I would call the highest levels of politics and power in America. Could you maybe just like give us some examples when you speak about like this kind of like scorn that you’re describing?

Sarah: So yeah, it’s funny. I actually don’t see it so much in politics because I think most politicians understand that America is a pretty religious nation, many of them are personally people of faith and they’re not going to, certainly not going to scorn people of faith. I more see it in elite spaces where, you know, I was just listening to a podcast and I won’t say who it was, but this, it’s fine.

Mijal: I wanna know who it was.

Sarah: This guy was being interviewed and he’s a very well-known atheist and he was speaking actually very respectfully. said, you know, I’ve come to realize that I’m sort of like someone who’s colorblind and that like people who have this faith in God, they can see colors and I can’t. And I’ve come to feel like they have something I don’t. And I thought like, that is so beautiful.

Then he proceeds to define God as this being in this guy who controls everything. And he’s like, and I just can’t believe it, but they can. And so they get to see in color. Wow. And I just thought like, you were so close, man. You were so close. But I don’t…

Mijal: Wow, that’s hilarious. I used to think of God as King Triton and the Little Mermaid when I was a kid. That was like my image of God.

Sarah: Can I tell you something? A friend of mine who is an American expat, Israeli citizen, raising Israeli kids, he’s playing with this three-year-old kid in the pool and there’s a lifeguard with this big white bushy beard and his son goes, oh, that’s God. And he’s like, no, sweetie, that’s Steve, the lifeguard. The kid’s like, Three-year-old Israeli kid. Amazing. So that’s where I see the score more there. In terms of examples, oh my God, there’s so many. Let me give a good example right now.

There is this old antisemitic lie that Christianity is a religion of love and Judaism is a religion of law and it’s weedy and legalistic and nitpicky. If you actually study Jewish law, what you find is this very high bar for love. Shai Held has literally written an entire brilliant book that’s called Judaism is About Love, and he is much deeper on this than I am.

But I’ll just give one very specific example. When you study, these are very basic texts that many people, Judaism 101 texts that you’ll learn in an intro Judaism class. So there is a text that says that if you are going into a store and you have no intention of buying anything, you’re just browsing, don’t ask the shopkeeper the price of an item. Because if you do that, you’re gonna get their hopes up and you’re gonna waste their time and you’re not gonna buy anything.

Another text I read recently said that if you have loaned someone money and you know they’re really financially struggling still and you happen to see them coming down the street towards you, you should actually just try to walk the other way because if you run into them, they’re going to be knowing they’re indebted to you. It’s like humiliating for them.

So you could say, like, wait a second, why don’t you just say, be nice to workers and be kind and give to the poor? Like you could say that’s so weedy, it’s so legalistic. But what Jewish law is actually trying to do with these very specific hypotheticals, and there are bazillions of them in Jewish tradition, what if this, what if that? They’re trying to actually cultivate within you this exquisite sensitivity to the individuality of every person who comes before you, to that person’s needs, dignity, humanity.

It is like going to the eye doctor when they click that little vision machine and make your vision crisper and crisper. Jewish moral and ethical law is trying to just get your vision crisper and crisper to see this particular person in front of you in all of their humanity and sensitivity and dignity and needs.

Now, why is that so counter-cultural? Well, it’s the exact opposite of so much of what we see on especially college campuses today, which is, no, no, divide the world up into two clumsy crude categories, oppressed, oppressor, powerless, powerful, and we love and hate them accordingly. That’s it. Which is essentially like taking that vision machine and clicking it backwards to make everything so blurry that all you can see are two big blobs and you can’t even see those blobs particularly well. It’s dehumanizing, right? It’s like Mijal, you are not Mijal, this person with this specificity, individuality, divinity, you’re just, I don’t know, what are you, woman of color? Let me just, I’m gonna throw some labels at you that fit into my weird American view of the world, whether or not you think, I don’t care what you think, here’s your category, you know what, you’re an oppressor. no, no, maybe you’re oppressed. I don’t know, it’s confusing, you’re Jewish, right? I don’t know, what are you? That is, you know, that kind of Jewish thinking of like, no, no, see each individual person, I think that is tremendously counter-cultural.

I’ll give one more, a quicker example. Modern secular culture is very much about like aging, grief, illness, dying, disgusting. We want nothing to do with any of that. Freaks us out, like hospitals, gives us the creeps, funeral home, dead people. No, no, hard pass. I will send some flowers, send a text. Whereas if you look at the Jewish laws around how do we treat people who are sick, who are dying, who are mourning someone they’ve loved, it’s the exact opposite. It says, run right up to them. You get up close to them as close as possible. You sit by their bedside. You sit next to that mourner.

After they have lost their loved one at what’s called a Shiva, you sit, it’s a seven day process where people come and they just sit with someone who’s grieving and they’re just with them physically right up close. You get right into those moments in life that are, where we’re our mortality, that are all about mortality. Whereas the secular world says, run from that. We have so many rituals to embrace all of that.

And just finally, I’ll just say overall, you know, so much of modern secular culture is like, my gosh, it’s about you. How is your wellness? It’s about you. Think about you. Put yourself first, how’s your wellness? How’s your happiness? Are you well? Beautiful. I think that is so great. Of course we should care about that. Jewish tradition does care about that, but it’s also kind of going to be asking like, what higher thing are you serving? Right? You can call that higher thing God. You can call that higher thing goodness, generosity, courage, self-sacrifice, self-restraint, self-discipline. You know, I think I visited 25 college campuses this year and the campus where I think the students were happiest was West Point because those students, are serving something so much higher. So like if they’re having a day where they’re not totally feeling like wellness, they’re like, well, I’m going to serve my country. They’re just in a bigger world. And I think that by this hysterical hyper individualistic focus on me, me, me, me, me, it’s going to make you miserable. Like, I don’t know how these poor Gen Z what we’ve done to them with phones and my God, I just, I like, I want to just hug them. It’s terrible.

Jewish tradition. It’s just, it’s a very, it’s a very, very different, very different.

Mijal: Let me ask you a question and I hope I can say it in the right way. A lot of what you are saying now is a way to kind of show how these ancient Jewish rituals and ways of being have tremendous value and actually should push us in countercultural ways, especially in comparison with what we can call like, you know, the secular West and kind of like secular Western culture.

I guess I wonder, are there parts for you in our tradition that actually know don’t actually feel as morally valuable?

And also I’ll say, Sarah, you’ve shared with me that you are going to start an ordination program soon, which means you’re going to not just talk about Jewish texts. People are going to come to you with like hard hitting questions and ask you to prescribe things, you know, not just describe them. but yeah, can you speak a little bit about what that looks like for you? I don’t know if you want to bring examples. But there are parts in this rich tradition that don’t make as much sense or really can trouble one.

Sarah: I totally agree. And here’s something again I want to push back on is when I’ve spoken about what we lost in transitioning to modernity, I get the straw man pushback of, you want to reject modernity. You don’t like logic or science or using your brain. Fine. I find that so maddening. No, no, no. I think we need to go back through our tradition using some of what we have in modernity, right? Like I like science a lot, really big into it. I like logic and reason.

I believe very strongly in LGBTQ rights. I believe in women’s rights. And so if you want to ask me the aspects of our tradition that I do think are problematic, I actually, think that some of the thinking around LGBTQ people, around women, to me is quite problematic, which is why I really so appreciate the denominations that have gone back through and said, wait a second, we’re going to do what we as Jews have always done and reinterpret our text in light of some of our moral development. And it’s a discernment project. It’s not all or none.

I there is some discernment here. I think it’s this black or white kind of thinking is just, it’s not very Jewish. If you go back through Jewish thinking, it’s so much of like holding opposing truths and both things are true. So what do you do in light of that? So I think, know, guess what? The Torah, the Hebrew Bible, Jewish Bible, it says an eye for an eye. Plain text is what it says. Ancient rabbis, ancient text, ancient rabbis looked at it and they said, no, no, no, no. We’re gonna interpret this. And they went through a very elaborate process and it’s wonderful and beautiful. They said, no, when you put out someone’s eyes, what this means is you compensate them monetarily. They re-imagined it, right? It wasn’t in line with their fundamental moral sensibilities. And that’s what we do. And sometimes it goes too far and sometimes we lose things, so we recalibrate. Yes, there are things I find problematic and I really appreciate the parts of the Jewish world that have rethought them.

Mijal: Yeah, interesting. I’m curious, in light of the things you’re saying, the top two questions or three questions that you meet Jews, you know, the questions that Jews are asking right now when they are thinking about faith, about who they are as Jews, especially in this post October 7th moment.

Sarah: It’s a great question. Most of the time, the number one question I get is what to do about antisemitism? Just number one question. Of course, it’s like so obvious. I have an answer which never makes anyone happy, happy to share it, but that’s number one. I think number two is like Israel. It’s not even a question. So it’s sort of an anxiety about Israel. And then think it’s third, it’s like, okay, I’m Jewish, like now what? Right, it’s like, wow, we’re Jews again. Like we had this great 80 years of being Americans of the Jewish faith, you know, and I think that we’re, and that was a wonderful vacation mystery, like fun times for all. And I think that vacation has ended in some ways. And you know, for some people, maybe it hasn’t changed all that much, but I think for most Jews they’re realizing like, wait a second, something’s different now. And what that something is is that we’ve returned to Jewish normal.

You know, Derah Horn kind of makes this point like this is normal, guys. You know, that 80 years was not normal. Now we’re back to normal. And I keep wondering, like, I wish my Bubby were still alive because I’d be like, Bubby, tell me about the 1930s. Like, how did that go here in America? You tell me about the 40s. Like, how did you do this? Because we’re a little we’re a little out of shape now in figuring this out. And I think we will. But it’s a little different. So those are the main questions people are asking.

Mijal: Let’s say you have a magic wand and you can really make some big changes in terms of how American Jews, either how they think about themselves and their tradition or what they do. How would you wave that one?

Sarah: So in the Hebrew Bible, our core sacred text, there is in some of later books, there is this moment where back yonder many, many years ago, Jews were exiled from ancient Egypt to Babylonia, and then they were allowed to return. And when they returned, it was pretty clear that the Jews who hadn’t left Israel, they’d kind of lost their practices, right?

Mijal: The locals, yeah.

Sarah: Yeah, so some Jews stayed. The elites were exiled. When the elites came back, they realized that the Jews who had stayed had really lost the tradition. And so this Jewish leader at the time, Ezra, kind of did this like big, just massive adult Jewish education class. We basically just read them the Torah and there were all these like ancient teaching assistants running around, kind of explaining it to people.

Many problematic things about that whole period. But I would love a massive Jewish adult education class. I would love for every Jew to have the opportunity to that I had wishes to grow up to become a Jewish adult. Hebrew school does not make a kid Jewish. A rabbi does not make a kid Jewish.

Mijal: It might even like work against it.

Sarah: Yeah, exactly, it might actually work against it. And by the way, I do not blame Hebrew school teachers for that. It is so unfair to say to a Hebrew school teacher, we do nothing Jewish at home and think Judaism is kind of dumb, but we’re cultural Jews, make our kid Jewish. Like, no, I want every adult to grow up. Like I had to grow up. I know it’s hard, not gonna lie. Take some time. You gotta read some books.

You gotta read books, that’s our tradition. Guess what Jews do? It’s so weird when we call, they read books. I get this weird pushback to this where people–

Mijal: Or listen to podcasts, just saying.

Sarah: Or listen to a podcast, listen to a lecture, however you learn is beautiful and I celebrate you. Learn Jewish tradition that way. Like study some of our key texts. I’m not talking about you have to learn Hebrew instead of the original. I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about like, let’s curate. I mean, I’m basically talking about read my book, which sounds so self-promotional. I don’t mean it that way, but like my

Mijal: It’s a great book.

Sarah: But my book is my answer to this question. Like, what do I want? I want people to know at least the stuff in my book. And I hope that knowing that stuff makes them realize like, this is just the tip of the tip of the tip of the tip of this large iceberg. Like, wow, there’s so much more. That’s what I would prescribe.

Mijal: Yeah, that’s awesome. And when is your next book coming out? Just so we know to get to get both books.

Sarah: So it comes out September 9th. You can pre-order it on Amazon now or maybe not.

Mijal: And it’s really helpful to authors to pre-order a book on Amazon. So I think everybody should go and pre-order your book on Amazon.

Sarah: It is, it is. Or elsewhere, know, HarperCollins probably has it somewhere where you can pre-order it. I don’t want to be pumping Amazon right now, but you know, anywhere you can pre-order it, would love it to be, called As a Jew.

Mijal: I wanna read to you, Sarah, something as we’re beginning to close up the conversation. There’s an essay that I’ve really, really loved and I wanna read to you a passage from it. It’s an essay that was actually published shortly after the Holocaust by Simon Rabidovich, who was like a thinker, a philosopher, wrote about a lot of different questions. And it was first published in Hebrew.

Eventually it was translated into English and the name given to the English version is Libertad de Ferendi, the right to be different. And when I came across it, I was really, really struck by it. What he does here is he, I’ll just give you a little bit of a context. He talks about, you probably know this better than me as a speechwriter, but Roosevelt had that speech of the four freedoms.

Sarah: Yeah.

Mijal: One of them is freedom of speech and expression. The second is freedom of worship. The third is freedom from want. And the fourth is freedom from fear. So what he adds to this, which I find really beautiful, is he argues that there’s a fifth freedom missing in the speech. And the fifth freedom is the freedom to be different. That you can actually be different.

And again, he’s writing this like in the wake of the Holocaust, right? So he argues that the existence of the Jewish people is actually almost like proof for this fifth freedom. So I’ll read to you a little bit from this, the English translation. He says:

The Jewish people is the outstanding different in the world. The greatest nonconformist history has ever known. At the very beginning of its career, it was characterized by two remarkable features. The first is being stubborn and stiff necked, a characteristic attributed to the Israelites by God himself after he had freed the people from Egypt, et cetera, et cetera. The second national feature was perceived by one of the greatest prophets of the Gentiles, Bil’am, who blessed the Israelites instead of cursing them, saying, it is a people that dwell alone. So we are stubborn and we dwell alone.

This, he says, and I’m skipping a little bit:

has been from Jewry’s infancy the main source of its superhuman suffering. Jewry has paid the highest price for this privilege of living alone on God’s earth. But then he keeps going and then he basically argues that this burden, in a sense, is what Judaism comes to give to the world.

And then he says:

the right of the Jews is based on this concept of this fifth freedom. I’ll read just a little bit more if it’s okay. He says, Jewry is different, but why and for what? What is the blessing in being different? Every camp in Jewry as every individual is entitled to formulate its own explanation and to a certain extent is even obliged to us the meaning of man’s existence in general and of the Jew in particular. We do not mind those who are less at home.

He continues to say:

we don’t mind those who try to ask, why are we different?

But then he says:

There’s just one condition that the search for reasons and motivations be addressed to themselves for the internal consumption of the house of Israel. Let them write as many apologies as possible under the title, why I am a Jew, but never with their face turned away from us. We owe no explanation, no reason, no apology, no justification for our particular way to the outside world. This world is not entitled to use our being different as an excuse for discrimination, to rob us of elementary rights as human beings or as a group wherever we may be. And then he says, this is not a privilege unique to the Jews. No group should suffer for it being different. As far as the world is concerned, we shall never and should never offer any accounting of our way. We should always say to the world, we are different because we dwell alone.

Pretty intense, right?

Sarah: It’s very intense. You know, I love Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, his book, The Dignity of Difference. You know, Judaism, we really believe that every human being is created in the image of God. Not every Jew, every human being. We believe that like every human being has rights and is equal and everyone should be able to thrive and be happy.

But we don’t proselytize, right? Unlike the two major world traditions to which half the world subscribes, they proselytize, right? The ideal in those traditions is that everyone should be of this religion. That’s not the ideal in Judaism. The ideal in Judaism is Jews should be Jewish and anyone who wants to be Jewish can be Jewish, period, right? We’re just trying to do us and they can sort of be them.

That difference is something that I worry we lose when we try to make being Jewish about just being a good person. The number of Jews who told me being Jewish is just about being a good person. like, as in…

Mijal: What do you say when you hear that Sarah? I’m so curious.

Sarah: I’d say that’s beautiful and that’s also what Christianity and Islam and Buddhism and every tradition and every decent atheist wants to be a good person. don’t own that. Jewish tradition has a unique, specific, totally individualist, just unique way of being good person, as does many, as do many other traditions and philosophies.

I’m not saying we’re better or worse, but there is something unique and special about Judaism’s idea about how you be a good person, about how you lead a meaningful and worthy life. And part of my faith, whatever that is, is studying that tradition, saying like, this is extraordinary. Like this is actually a time-tested, wise, profound, challenging, not gonna lie, it’s challenging. You gotta do some work, gotta read some books, God forbid.

This is a really like, the product is good. It is the wisdom of millions of my ancestors over thousands of years and it’s good. I’ve studied it. So much of my faith in this is in my ancestors and it’s also in the Jews I know now. And I think as I have become deep, more and more enmeshed in the Jewish community, I just keep meeting people in whom I have faith. Like this person is a good person. This is a moral person. This is someone I respect and admire.

And I see them engaging deeply in Jewish tradition in all sorts of ways, by the way, very diverse Jews who I just respect so much. If you want to talk about faith, like that’s where I draw so much of my faith. So, you know, a man in the sky who controls everything, like I don’t even know what you’re talking about. So I think I like this broader idea of faith in the tradition, faith in my ancestors, faith in what our people and where we have been and what we’ve done. That to me is a key part of my Jewishness.

Mijal: Yeah. Yeah. The, the, the reason I brought up this quote about the freedoms is that so much of what you’re pushing us, I think Sarah, to do with both your, your first book and your, upcoming book and everything you’re saying is really to encourage just to not be afraid to hold on to this particularistic tradition, to explore it, to grapple with it and to be proud of it.

Sarah: Yes. and I want Jews to understand how anti-Judaism and antisemitism has very much colonized Jewish identity, how it is very much…

Mijal: That’s a big sentence. Yeah. You want to break it down for us?

Sarah: It’s big sentence. know I said this. You know, as I was trying to figure out why did I spend my whole life being like, I’m just a cultural Jew, ha ha, social justice is my Judaism, ha ha, I like Seinfeld, ha ha, please love me, I’m the same as you. And I look back at my childhood Judaism, which was so edited, I was like, what happened? And I think a lot of our reaction to modernity and our creation of these various ways of being Jewish, it was in that atmosphere of 2000 years of Christian anti-Judaism, which has a just constant drumbeat of Jews are powerful, depraved and in a conspiracy. And they’re disgusting and vile. I mean, it’s just such an awful way of thinking about Jews that I think we over the time have internalized. And I think that did very much shape the kind of Judaism that we created back then.

And how could it not have? It’s extraordinary that we’ve lasted this long. Like I can’t even believe what our ancestors did to recreate a Jewishness that would last. Like they are heroes. I’m Jewish because of them. Let me be very clear. And I think that these tropes and themes about Jews have just so kind of infected us. And I think we have to be aware of them and aware of how they shaped us so that we can strip them away and re-approach Judaism on Jewish terms, right? Re-approach it with curiosity and reverence and openness without all of these, all of this negative, this kind of lens that has been put on it by others. And I think stripping that away is so important for figuring out how to re-embrace our tradition.

And I still struggle with it. I still see myself trying to, know, Dara Horn has this wonderful article called The Cool Jews, where she talks about, you know, there’s one kind of antisemitism, which is like, the Jews are bad, we kill them. That’s the Holocaust. Then there’s the kind that says, yeah, the Jews are bad, but actually there’s something they can do to save themselves, which is to reject whatever it is about Jewish civilization that we hate. So look, back in the day, reject Judaism, become a Christian, yay. My parents’ generation, reject your name, your nose, your hand gestures, become a WASP, you’re great. Today, college students, you reject your Zionism, you convert to anti-Zionism, then you’re saved and you’re a good Jew.

And I see myself doing it. I see myself being like, I’m not, not, I still see myself, I’m not that religious. Why would I say that? I’m not that religious? Okay, what if I were? Is that a problem? Why do I have to keep telling people that kind of thing? It’s almost like a tick at this point and I see it.

Mijal: It’s the double consciousness, right? The seeing yourself through the eyes of the world.

Sarah: Exactly. Exactly. And it’s very hard to strip away. I think a lot of, and by the way, this isn’t unique to Jews. All kinds of minority communities have grappled with these things with a lot of sophistication that I think we maybe could learn from. We’re not alone in this.

Mijal: So Sarah, we discussed so many things, so many takeaways from just thinking about counter-culturalism, about the value of Judaism to secular life, to also just to encouraging people to study, to take texts seriously, to your vision of a thick Judaism that is diverse and that wisely chooses some modern tools but not others and doesn’t internalize the hatred of the world too much.

I wanna ask you just one last practical question and with this we’ll conclude. I’m very lucky to meet a lot of Jews who as adults in this last year and a half, they come and they say, I didn’t learn enough, I didn’t get the education I wish I had, now I want to learn and it’s so much out there. And I have like a couple of books that I recommend, yours is one of them.

But I’m curious, when you meet individuals who come to you and they tell you, I’m in my 40s, in my 50s, my 30s, whatever it is. And I have all of this life of knowledge. How do I start now? What are some of the recommendations that you give them?

Sarah: I mean, definitely, books are just, can kind of do it in the privacy of your home at your own pace, not too much pressure, right? For people who are feeling anxious, that’s a great first step. I also really recommend taking a good introduction to Judaism class, right? Don’t do this alone. Like be in a community, have an educator or a rabbi who can kind of walk you through it. So you’re part of a community. You know, think just taking a class, I took two intro to Judaism classes. No joke, two intro to Judaism classes.

Mijal: You are introduced twice.

Sarah: I was introduced twice and I needed it. It was actually really helpful to me. I also think once you have the basics, once you know what the basics are, start to follow your passion. If you think like you learn about Shabbat and you just think this is so great, amazing. Lean into Shabbat, host Shabbat, go to Shabbat. If you think Jewish spirituality is so intriguing, there are Jewish meditation retreats, there is all kinds of interesting Jewish prayer and study. Lean into that. If you love Jewish ethics, if you like to study and argue, pursue that, like there are just so many, once you know the basics, think kind of leaning into where your curiosity and your joy lead you, you’ll get the rest of it as you go, right? All of Judaism is hyperlinked to everything else. So if you’re learning more about Shabbat, you’re gonna be learning more about Jewish history and philosophy and so many other things. So no matter what avenue you pursue, you’ll be learning about the whole as well.

Mijal: Yeah, I love that. I’m going to use the hyperlink idea. Sarah, thank you so much.

Sarah: I think that’s actually Jonathan Rosen, believe, is his wonderful book, The Talmud and the Internet. Amazing book. I highly recommend it. also brilliant. Yeah.

Mijal: Amazing. I read his book, The Best Minds. It was one of my recent reads. So good. So good. Well, this was amazing. Thank you. Thank you so much for coming, Sarah. I really, really enjoyed speaking with you. Missing Noam, who’s not here right now.

And just as we’re closing out this week’s show, a reminder again to all of our listeners that we really love to hear from you. So please get in touch if anything resonated, if you have a question, if you disagree, anything, or just to say hi. It’s all a beautiful community effort and it’s really fun to hear from you. Next week, I’m really excited to have Noam back in the co-host hot seat where we’ll continue to speak and wonder about faith, which is a really, really exciting topic. And once again, a huge thanks to Sarah Horowitz for coming today, and I look forward to wondering with all of you again next week. Bye for now.