Shortly after Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) drove Bashar al-Assad out of Syria last year, the group pledged to respect the rights of minorities. Yet, since HTS took control over much of the country, some across the international community have raised fears that Syria’s new leaders—with their jihadist backgrounds—might erode minority rights or exclude these communities from the political transition process. These fears have been newly flamed by the massive, targeted violence against Alawites on Syria’s coast during the second week of March. Nevertheless, there have been some signs for optimism about the inclusion of at least some minorities in post-Assad Syria.

This analysis draws on my conversations with members of these groups as well as HTS leadership over the past several years as a consultant with the International Crisis Group and an independent researcher. The people I spoke with were granted anonymity given the tenuous security situation in the country and their ongoing political work.

There are legitimate reasons for worry, specifically about the future of the Alawite community. In March, Alawite insurgents linked to the former regime launched a coordinated attack against security forces. Government forces, independent armed factions, and Sunni vigilantes mobilized in response, engaging in nearly four days of mass executions, killing more than six hundred Alawite civilians and detained insurgents. The insurgency by ex-regime elements is still ongoing.

This violence and the state’s inability to control both its own forces and the independent forces has reignited fears over minorities’ safety, but these devastating events should not be viewed as indicative of the fate of other minorities. The violence is rooted in the fact that, over Syria’s brutal civil war, Alawite men formed the core of the regime’s fighting forces and intelligence apparatus and that the Alawite sect has come to be linked to the regime via both Assad’s policies and Sunni extremist narratives. These political and social dynamics do not apply to other minority groups.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

For the other minority groups, there are positive indications that they will be included in post-Assad Syria. Even before entering Damascus, HTS had been reaching out to Syria’s minorities in Idlib for sensitive, but successful, diplomatic engagement for five years. Christian leaders in Idlib told me in a meeting in 2022 that HTS had consistently reached out to them, first through senior religious figures and then through dedicated political attachés. HTS appointed these individuals—and thus engaged with these communities—directly, rather than through the Syrian Salvation Government that HTS and other opposition groups had formed to administer Idlib. These political attachés came to serve as advocates for the local communities, representing their demands to the Salvation Government and HTS security forces.

Through this, Christians in rural Idlib gradually regained control over their homes and farms and restarted public prayers. Additionally, security forces halted attacks on Christian communities. The engagement process was long and arduous, and, as HTS leaders told me in 2022, early on they were fearful that they’d face backlash from hardliners and populists in Idlib. However, as the years passed and the Christian community grew ever more integrated into Idlib’s society and the local government, HTS’s fears gradually ebbed.

Growing from this experience, HTS engaged with Syrian community and diaspora leaders just days into its final military offensive in late 2024. This diplomatic offensive helped ensure that HTS could sweep through Syria without taking many minority regions by force. The discussions, which took place primarily during the first week of December last year, resulted in a particularly strong relationship between HTS and Syria’s Christian and Ismaili minorities and also ushered in a new era of relations with groups previously seen as close to the regime.

A diplomatic offensive, from Nubl and Zahraa . . .

For example, the collapse of the regime in Aleppo in November last year spread panic through the nearby Shia towns of Nubl and Zahraa—once lynchpins of the regime’s defensive lines. Local Facebook pages claimed that two thousand Shia civilians had fled their homes, seeking shelter first in Aleppo and then in the town of Safira, where Hezbollah and Iran had built a strong militia network. By December 1, Safira came under at least partial opposition control, and regime forces abandoned the displaced people, resulting in widespread panic on Facebook over the fate of the civilians. On December 2, negotiations officially began between HTS and leaders from the displaced community to return them to their homes in Nubl and Zahraa, according to what an individual who facilitated the talks told me.

The negotiations began after members of the displaced community were able to reach one political activist living abroad, who told me that he helped establish a line to HTS’s political bureau and helped mediate. This initial experience quickly evolved into a small, multi-sect organization of activists representing a range of communities still under Assad’s rule—particularly the Ismaili-dominated cities of Masyaf and Salamiyah—all eager to assist in the peaceful handing over of their communities.

. . . to eastern Hama

This diplomatic approach expanded as HTS advanced on northern Hama. The city of Salamiyah, lying east of Hama, played a crucial role in the regime’s defense as it hosted the headquarters of several important regime militias operating in the countryside. But it also had a vibrant revolutionary movement dating back to the 1980s, particularly led by its Ismaili majority. “Ismailis have always opposed the regime,” one Ismaili activist told me, “but we work through political and civil means, not arms.” Salamiyah is also home to the Syrian National Ismaili Council, which supports and guides the Ismaili community across Syria. These factors opened the door to negotiations with HTS.

I spent several days in Salamiyah in early February, meeting with National Ismaili Council leader Rania Qasim and other security and civil society officials in discussions about the negotiations and resulting relations with HTS. According to Qasim, on December 2, HTS’s political bureau contacted her to initiate talks. The talks were led by Qasim and a representative from the Aga Khan Foundation, an international Ismaili humanitarian organization. The negotiations also included a coordination committee formed by the Ismaili Council’s Emergency Operations Center. Qasim told me that she and the other leaders of the negotiations saw themselves as participating in such talks on behalf of all communities across the Salamiyah region, not just Ismailis.

According to Qasim, the discussion focused on the fate of regime fighters in the region and on how HTS would enter the city of Salamiyah. The council, according to the people I spoke with, refused to provide cover for any criminals in the city, agreeing instead to HTS’s general taswiya (settlement) policy—employed nationally after the fall of Assad—that saw a grace period for all armed men to turn in their weapons and receive temporary civilian identification documents, but it did not provide them with blanket amnesty. In return, it was agreed that pro-regime fighters would lay down their weapons while HTS units simply drove through the main street on their way south to Homs. The coordination committee also agreed it would send a delegation to the outskirts of Salamiyah to meet the HTS convoy and escort them through the city.

These negotiations marked a significant first step in HTS’s relationship with the Ismaili community in Salamiyah. According to Qasim, the council spent the three-day negotiation repeatedly announcing to Salamiyah residents, “the council and the community will not fight; if you want to fight, it will be your own decision.” This message was carried even to some of the most infamous Alawite villages, such as Sabburah, where two pro-revolution Alawite ex-political detainees then worked within their village to ensure the local fighters agreed to lay down their weapons. Yet the Ismaili Council itself has never been affiliated with any armed faction and had no communication with regime military leaders; Qasim emphasized that at no point did they negotiate with or on behalf of any armed regime faction.

Instead, HTS leaders had to trust that the Ismaili Council had the influence needed to pacify the regime militias and ensure HTS’s safe entry into the city and surrounding villages. In fact, there was only one small skirmish—in the village of Tal Khaznah, on the road south to Homs—but otherwise, the handover of eastern Hama on December 4 was peaceful, local security officials and members of the Ismaili Council told me. According to Ismaili leaders in Salamiyah and Tartous, the Assad regime responded to these rapid negotiations by sending security officials to the Ismaili Council in Tartous and threatening them, telling them that their relatives in Salamiyah were “traitors.” However, the regime collapsed before these officials could follow through on any threats.

I was told that throughout this three-day negotiation period, other negotiations also took place on a more individual basis. Opposition fighters from both HTS and other factions who were from Salamiyah had begun reaching out to friends and families in their villages. One young commander remembered calling his family as his unit approached eastern Hama and asking them to connect him with the village’s mukhtar, telling me, “why would I want to risk fighting my father or brother?” He now leads a general security detachment in the countryside around his mixed-sect village, where he sees himself as bound to protect all locals no matter their sect.

The handover of the Salamiyah region was only the beginning of talks between HTS and the Ismaili Council, according to the Ismaili leaders I spoke with. The national council oversees seven regional branches, including ones in Tartous and Masyaf. With the regime still in control of western Syria, the Ismaili Council began negotiating on behalf of communities there. For its part, HTS ended its operations on the Masyaf front the same day it liberated Hama city, pausing its westward advance at the edge of the Ismaili- and Alawite-inhabited foothills. Ismaili leaders also told me that they began to share their positive experiences engaging with HTS with their contacts in the heavily pro-regime Christian towns of Muhradeh and Suqaylabiyah, which had ceased fighting but remained besieged by HTS. Those towns quickly concluded their own negotiations, which saw the peaceful entry of HTS units.

A foundation for a new Syria

The initial negotiations appear to have laid a strong foundation of trust that has extended beyond Salamiyah. According to the head of the Tartous Ismaili Council, HTS’s local military official met with the council the day after entering Tartous. The council was then invited to a general meeting between local representatives and HTS officials, was given a new line of communication with HTS’s political representative, and finally was welcomed to meetings with the new administrator of Tartous governorate. All of this evolved over just ten days. As one Ismaili official in Tartous described it to me, “It seems that the new government truly respects and has a special relationship with the Ismaili community. This came as a huge shock because we had never spoken with them before and had the same fears as the Alawites until December.”

HTS’s diplomatic offensive demonstrates the leadership’s political approach, which evolved over years of engaging with the Christian and Druze communities in Idlib. HTS leaders had justified these new policies to me years ago as a political necessity for one day governing a country as diverse as Syria and for legitimizing the movement among minority communities who only knew of the organization from its days as an al-Qaeda affiliate, then called Nusra Front. This understanding that Syria cannot be ruled as an Islamist Sunni country (but instead must be led as a country of diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds) has begun to shape the post-Assad era—at least at a local administration and security level.

The initial Salamiyah negotiations laid a strong foundation of cooperation that has continued to grow, ensuring the Ismailis across Syria “feel confident we will be fully represented in the constitutional process,” as a leader from the Tartous office told me. In Salamiyah, the Ismaili Council now plays a central role in the region’s administration, facilitating civil-political engagement, running a volunteer security force to assist local police, and hosting a security committee consisting of both civilian and military representatives to address security gaps and any violations committed by government forces.

Such relations have grown even stronger in the coastal city of Qadmus. According to two local Ismaili activists I spoke with, a small Ismaili volunteer force has been supporting the undermanned government police forces in Qadmus since December. Government forces have even provided these volunteers with small arms, while a new Ismaili-run local council has worked closely with the regime-era mukhtar—also an Ismaili—to coordinate services and administration with the HTS-appointed regional director. The council has also engaged in outreach with the Alawite villages around Qadmus, serving as a bridge between the new local administration and the Alawites.

Despite these efforts, their close relationship with the new government has made the Ismailis in Qadmus a prime target for pro-Assad Alawites, who killed two Ismaili security volunteers in late February and an Ismaili Council member and two government police officers on March 6. When the March uprising began, the Ismailis tried to protect the government forces in the town, eventually negotiating for their safe exit from the area after being besieged by insurgents. However, as a result, they faced widespread threats—by Alawites both in person and over WhatsApp—for “siding with the government,” local residents told me. Security forces eventually peacefully reentered Qadmus, and according to the locals I spoke with, the experience has only strengthened their ties with Damascus. Many Ismaili men have now volunteered to support government security forces, with at least some applying to become official security officers. Meanwhile, local security officials are discussing extending salaries to the entire volunteer force. Despite the events of the past week, the city’s local council continues to serve as an intermediary between local security forces and the Alawite villages, as the former works to negotiate the handover of weapons and wanted criminals.

Meanwhile, Christian civil society leaders in Syria’s tense coastal region also described a strong working relationship with local HTS-appointed administrators and security officials. Although they still have concerns centered on basic services, the economy, and the constitutional process, several activists and local Christian leaders told me in February that they did not fear direct attacks from the new government but rather worried about being caught in the growing violence between Alawites and government forces. Christian leaders across Syria were among the first men engaged by pro-opposition security forces in the days after Assad’s fall, with Facebook pages publishing pictures of meetings between military and political leaders and religious figures in rural Damascus, Homs, and Aleppo. As the violence on the coast escalated in March, the head of Aleppo’s Catholic community, Bishop Hanna Jallouf, reiterated the importance of a united Syria, affirmed the good treatment of Christians across the country, and called for a continuation of efforts to fully integrate all minorities into the political process.

These new interfaith and civil-centric networks and relationships will play a central role in shaping post-Assad Syria. However, the new government should do more to engage and empower groups such as the Ismaili and the Christian communities. It should do so both on a local and an international level, by working with groups such as the Aga Khan Foundation (to give Ismailis assurances) and even the Vatican (to do the same with Christians). Such efforts would help expand the local trust built with these groups into genuine representation in Damascus and would give real reason for optimism about the future of Syria’s minorities.

Gregory Waters is a researcher at the Syrian Archive, an associate fellow at the Middle East Institute’s Syria Program, and a research analyst at the Counter Extremism Project.

Further reading

Tue, Mar 18, 2025

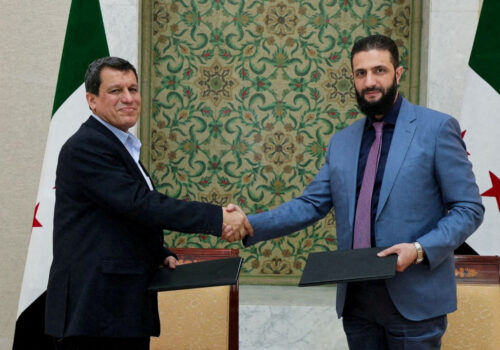

Landmark SDF-Damascus deal presents opportunity, and uncertainty, for Turkey

MENASource By Ömer Özkizilcik

Despite positive signals, critical ambiguities remain in agreement between Syrian President Ahmed Shara and SDF commander Mazloum Abdi.

Mon, Mar 10, 2025

Syria’s women face a new chapter. Here’s how to amplify their voices.

MENASource By Diana Rayes , Hind Kabawat

It is critical for women to be involved in transitional justice and constitutional reform processes in Syria.

Wed, Feb 26, 2025

Why post-Assad Syria complicates the Iran-Turkey rivalry

MENASource By

Depending on what unfolds after Assad's fall, there could be reason to expect a degree of Iran-Turkey alignment in Syria.

Image: People attend a protest against the burning of the Christmas tree in Hama, in Damascus, Syria December 24, 2024. REUTERS/Amr Abdallah Dalsh