"Terrifying": US aid cut puts Namibian trans lives at risk

What’s the context?

Majorly restricted US funding provides crucial trans healthcare in Namibia, and specialised clinics are already closing.

WALVIS BAY, Namibia - Ruann moved to Walvis Bay for the same reason many other trans women are attracted to the Namibian port town: to find work.

The city sits where the Namib desert meets the Atlantic Ocean, the only natural harbour in this southern African nation, making it a bustling hub as goods from shipping containers are offloaded into trucks setting off for Botswana, Zimbabwe and Zambia.

This flow of 8 million tonnes of cargo a year brings about 900 ships to the city, and with them are more potential clients for Ruann. But like many sex workers, Ruann’s job puts her life at risk.

“We are pushed to have unprotected sex,” Ruann told Context. “How will I ask my client, ‘What is your status?’”

Ruann, who declined to give her surname, relies on a clinic specialising in trans healthcare to get tested for HIV and receive regular doses of pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, a measure that prevents contracting the virus. But the clinic is heavily funded by the United States, and Ruann’s access to that care hangs precariously in the balance as President Donald Trump’s administration dismantles the U.S. Agency for International Development, or USAID, which administers foreign aid.

“It’s going to be terrifying for me if I can't access health services,” she said.

High risk

On paper, the country of 3 million people is one of the most progressive on the continent for LGBTQ+ rights. But transgender people in Namibia are still left behind when it comes to healthcare. Even if they get past the stares and whispers of a waiting room, a doctor may intentionally misgender them.

Ruann has experienced this firsthand. When she was 18, she suffered an acid burn that led to a stay in hospital. A male nurse treating her asked, “Why are you acting like a girl when you know you are a boy?”

“It started to become like I'm on a comedy show because everybody's now laughing while the nurse is busy attending to me,” Ruann said.

Ruann said she was misgendered and harassed by a nurse when being treated for an acid burn when she was 18. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Ruann said she was misgendered and harassed by a nurse when being treated for an acid burn when she was 18. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

When bathing her, Ruann said the male nurse pointed to her genitals as proof of her “real” gender, then cut her hair under the guise of treatment even though the burn was on her arm. “It was just a horrifying experience,” she said. “And that's when I decided I'm not going back to any state facility.”

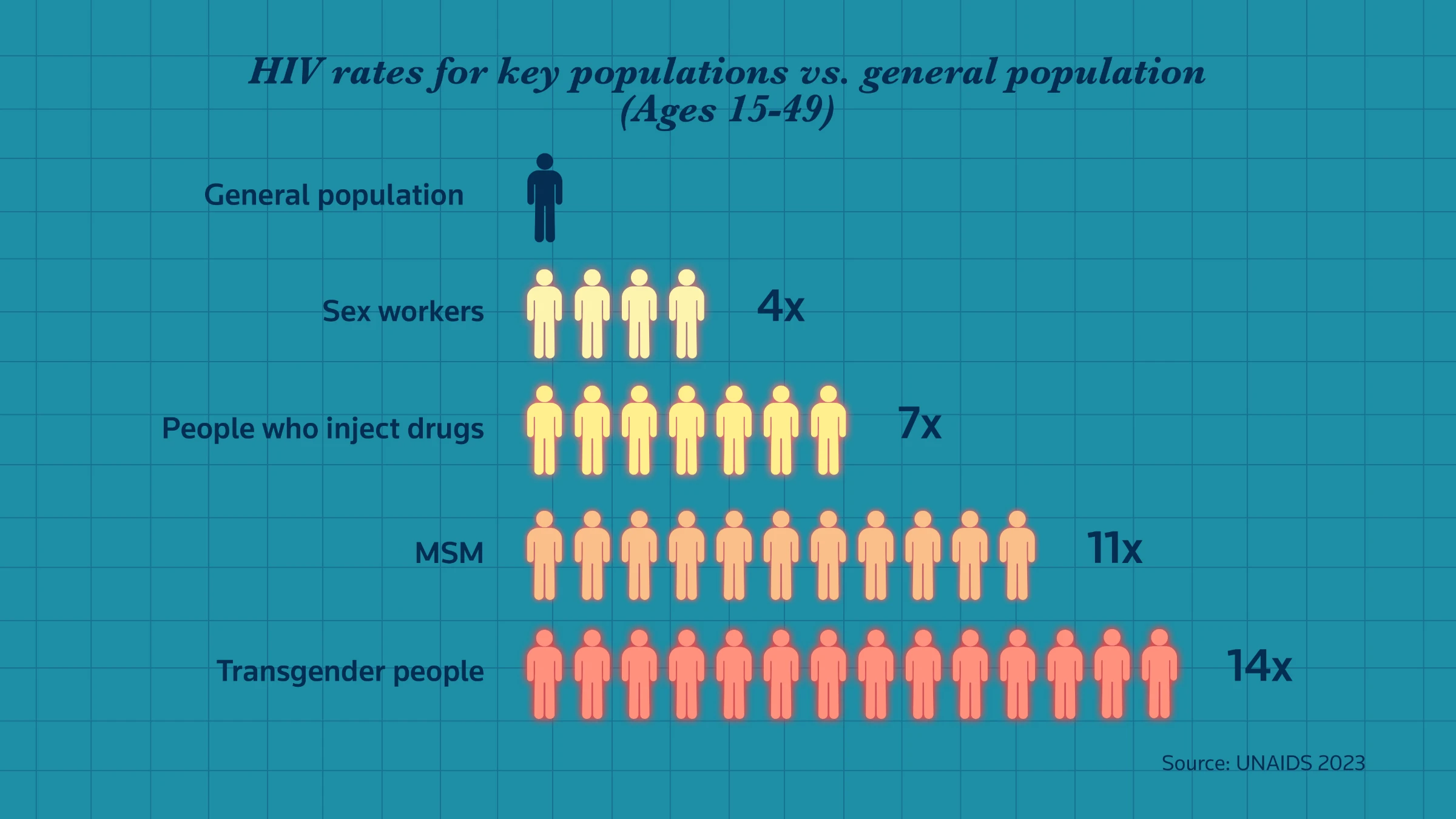

But as a sex worker in a port city, Ruann is at high risk of contracting HIV, and being trans only heightens the risk. Sex workers are four times more likely to contract HIV/AIDS compared to the general population, and transgender people are 14 times more likely, according to data from UNAIDS, the United Nations’ main agency working on the epidemic.

That’s why international donors have focused on transgender people and sex workers, two groups they call “key populations.”

The United States has funded the single largest donor programme for the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS, investing $110 billion in 55 countries under the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), launched by George W. Bush in 2003.

Over most of its 20 years, PEPFAR has enjoyed bipartisan support and had staggering success – saving more than 26 million lives, providing more than 83 million HIV tests and helping 7.8 million babies be born HIV-free.

“PEPFAR has been the primary support for those types of clinics where governments have not stepped in,” said Beirne Roose-Snyder, a Washington-based senior policy fellow with the Council for Global Equality.

HIV and AIDS remain the leading cause of death in Namibia, where some 230,000 people have the disease. But the country is seen as one of the most successful in slowing the spread of HIV. New infections have fallen by 54% between 2010 and 2022, UNAIDS has said, and experts credit community-focused HIV prevention and treatment programmes as being a part of the success.

Mobile clinics, discreet treatment centres and sensitised staff are just some examples of how this support has radically changed healthcare for trans Namibians.

A case worker with a PEPFAR-funded project, Pitti Peter, helped Ruann seek healthcare again after her troubling hospital stay as a teenager. Peter took her to a discreet clinic in a converted shipping container, tucked behind a tall wall in an industrial part of town.

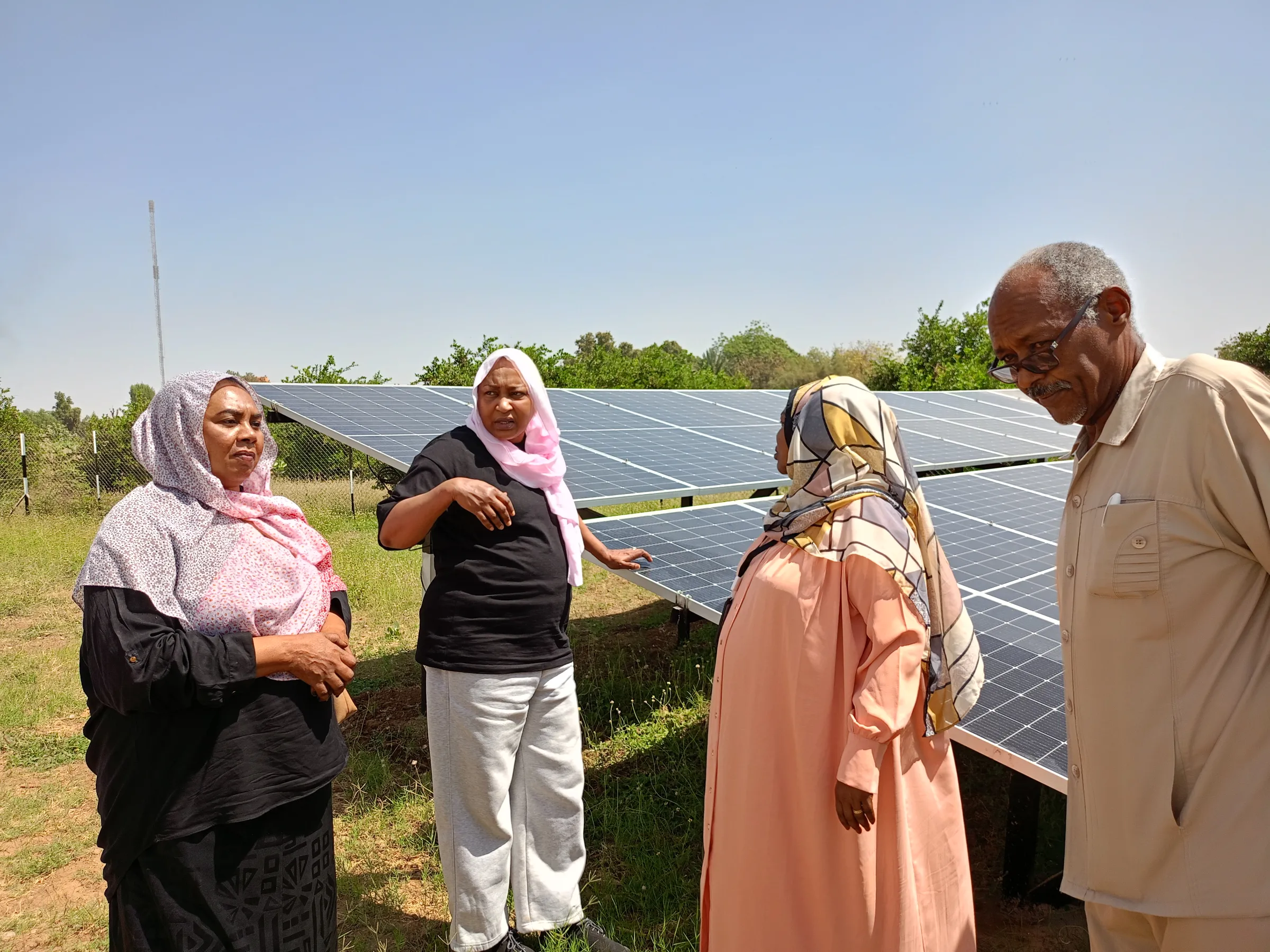

The Namibia Planned Parenthood Association operates mobile clinics offering sexual health advice, testing and items like condoms and lubricant. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

The Namibia Planned Parenthood Association operates mobile clinics offering sexual health advice, testing and items like condoms and lubricant. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

“PEPFAR funding under the USAID created such a welcoming environment,” said Peter, who supports trans sex workers through the Namibian Sex Workers Alliance and is a trans woman herself.

The support Ruann received at the Walvis Bay Corridor Group clinic helped her feel comfortable taking PrEP and receiving other care, like screenings for blood pressure and sexually transmitted diseases. The services have been funded by PEPFAR and USAID, under a key population project implemented by a local nongovernmental organisation, IntraHealth Namibia.

Brihana, a 28-year-old trans woman, receives care at a Walvis Bay Corridor Group branch in the capital Windhoek. Before finding the clinic, she had faced medical staff who laughed at her and questioned her gender. An emergency room doctor once told her that “you people” annoyed him as she sat with a bleeding gash in her forehead, leading Brihana to avoid healthcare services altogether.

A friend introduced her to the Walvis Bay Corridor Group, which provides taxis to reach appointments and ensures trans patients do not have to sit in waiting rooms with other patients.

“They were the ones that actually put me back together, and that's when I felt very safe,” Brihana said. “Finally, some people are hearing our voices.”

Minimising visibility is a priority at a time when trans Namibians face a dangerous backlash to recent court decisions that expanded rights for same-sex couples. Since 2023, six trans Namibians have been killed for their identity, rights groups have said.

This climate makes protecting trans-specific medical services crucial, advocates say. But now the funding that keeps these clinics open is in jeopardy.

“Everybody's affected, and everybody is confused,” said Peter.

'Weaponising' PEPFAR

PEPFAR is currently facing dual threats in the United States. Even before Trump froze humanitarian assistance as part of his “America First” foreign policy, members of the Republican party had expressed opposition to the programme.

“There has been a very concerted effort to weaponise and target PEPFAR by political actors in the United States,” said Roose-Snyder.

Republican Congressman Chris Smith is a leading opponent of PEPFAR.

“Regrettably, it has been reimagined—hijacked—by the Biden Administration to empower pro-abortion international non-governmental organizations, deviating from its life-affirming work,” Smith told the House of Representatives in September 2023, when he argued against reauthorizing PEPFAR for its usual five years.

HIV rates in the general population compared to key populations, based on available global data from UNAIDS. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

HIV rates in the general population compared to key populations, based on available global data from UNAIDS. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

Conservative think tanks and anti-abortion groups in the United States, along with African political and religious leaders, have echoed these concerns. By law, PEPFAR cannot fund abortion. But in January, four cases in Mozambique of nurses performing abortions in PEPFAR-funded facilities were uncovered, the only such cases ever found in the programme’s 20-year history, according to U.S. officials.

Republican lawmakers had already managed to shrink the funding cycle from five years to one year, and it currently runs out at the end of March. And there’s an even bigger threat on the horizon: the slash-and-burn of aid funding under Trump.

Despite a waiver on lifesaving assistance, the halt in U.S. aid has already resulted in the shutdown of clinics. The Walvis Bay Corridor Group has had to close three out of its eight clinics across Namibia as of the end of December, when a funding agreement ended. Initially, the organisation expected bridge funding to get to the end of March.

That means patients have gone for more than two months without testing, counselling and, most alarmingly, treatment.

Preventative measures have been taken away from key populations like transgender people. The U.S. State Department’s waiver on some PEPFAR services during the 90-day suspension of foreign assistance mandates that PrEP only be given to pregnant and breastfeeding women.

A large-scale study has shown that those with intermittent access to treatment see the disease progress at twice the rate of those who have regular treatment.

“If I’m not protected … you are putting the entire country at risk,” Peter said.

“We are engaging in sexual activities with the general population. And that becomes a problem for the entire community at the end of the day.”

A nurse at the Walvis Bay Corridor Groups provides a transgender patient with condoms, part of HIV prevention care funded by PEPFAR. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

A nurse at the Walvis Bay Corridor Groups provides a transgender patient with condoms, part of HIV prevention care funded by PEPFAR. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Karif Wat

While PEPFAR funds specific services, it has also strengthened healthcare systems at large by providing steady funding for 20 years. This includes training healthcare workers, upgrading lab facilities and consolidating knowledge on how to treat vulnerable groups like trans people.

Ad hoc initiatives have cropped up in Namibia in recent years, such as healthcare workers reaching out to nurses who treat trans patients for advice, and more formal efforts, like sensitivity training for nursing programmes by a trans-led nongovernmental organisation.

But healthcare workers, advocates and patients said the system is not ready to go cold turkey.

“If non-government organisations are not helping, then the government will be overwhelmed, and the burden will be too much on them,” said Maria Nghishoongele, a nurse with the Walvis Bay Corridor Group. “They are likely not to be able to cater to everyone — community health will be at risk.”

Namibia is close to reaching the UNAIDS target of 95-95-95 for 2025, in which 95% of people carrying HIV/AIDS know their status, 95% of those who know their status are on antiretroviral medication, and 95% of them have a suppressed viral load, meaning they will not pass on the virus.

But leaving out vulnerable groups could roll back the country’s gains made in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

“We can't reach any of those goals without the inclusion and leadership of transgender people,” said Roose-Snyder, adding that their exclusion in healthcare will only “drive the HIV epidemic.”

This story is part of a series supported by Hivos's Free to Be Me programme.

Reporting: Sadiya Ansari

Additional reporting: Enrique Anarte-Lazo

Editing: Ayla Jean Yackley

Illustrations: Karif Wat

Production: Amber Milne

Tags

- Government aid

- LGBTQ+

- Economic inclusion