Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

- Genealogists in the Looted Books Project returned a stolen book to a 103-year-old Holocaust survivor.

- The project aims to return books looted by Nazis to original owners' descendants.

- Karen Franklin calls it a sacred task to repair the world.

SALT LAKE CITY — Genealogists volunteering for the Looted Books Project recently returned a volume to a 103-year-old Holocaust survivor in Florida who was given the book in 1930 as a gift for her good performance in Hebrew school.

It's rare that books the Nazis stole from Jews during World War II end up with their original owners. There aren't many actual Holocaust survivors alive anymore.

"This is really special in 2025 to be able to do this," said Karen Franklin, director of outreach at JewishGen and director of family research at the Leo Baeck Institute, both in New York.

JewishGen is a website for Jews and others seeking out their ancestors, similar to FamilySearch or Ancestry. It started as a bulletin board in the 1990s before the internet. The Baeck Institute is a research library and archive focused on the history of German-speaking Jews.

A sacred task

Franklin and Avraham Groll, vice president and executive director of JewishGen at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York, were in Salt Lake City last weekend for the RootsTech family history and technology conference, which drew 20,000 participants.

While in Utah, Franklin and Groll met with leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Family History Museum, FamilySearch and Ancestry to share the projects they're working on. Franklin's and Groll's passion for their work was evident in the meetings.

Franklin also sat down for an interview as part of the Deseret News' "Yellow Couch" series.

"For us, doing our research is not just about finding names on a page or on a tree but really recreating a line to the past that in many cases was severed during the Holocaust," said Franklin, a world-renowned expert on German Jewish genealogy.

"This is for us a sacred task, and also a very satisfying and rewarding one."

That sense of satisfaction and reward came through with the return of the book to the 103-year-old Holocaust survivor. The genealogist who tracked her down had her great nephew present the book to her. Up to then, she had shared little with her family about her experiences.

"They did not know much," Franklin said. "At that moment when she received the book from her great nephew, she told the family stories that they had never heard before, that they had never known. And now she has opened up after all these years."

Tikkun olam — repairing the world

The Looted Books Projects started about 30 years ago in Nuremberg, Germany, where 10,000 books were found in the library of Julius Streicher, a notorious Nazi who founded and published the virulently antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer. Nazis mostly looted the books from Jewish homes. Streicher was convicted of war crimes and hanged in 1946.

About 2,000 books contained the name of the original owners and half of them were returned to their families.

More recently, genealogists at JewishGen and the Baeck Institute volunteered to help search for the descendants of the book owners. They've managed to return more than 100 books in the past few months. Their work helps correct an injustice.

"When they heard about this project, I believe they were all inspired by a concept called tikkun olam — to repair the world. They all wanted to repair the world in their little way," Franklin said. "This is really a wonderful way to use genealogy research in really helping others."

It's not just Jewish genealogists volunteering with the project. Franklin spoke last year at a conference where afterward an evangelical Christian college student asked how she could get involved. She became an intern for the project.

"That was so meaningful because it showed to me the universality of the desire, that it's not just within our own community, but others understand respect and feel the joy in participating," Franklin said.

Connecting with the past

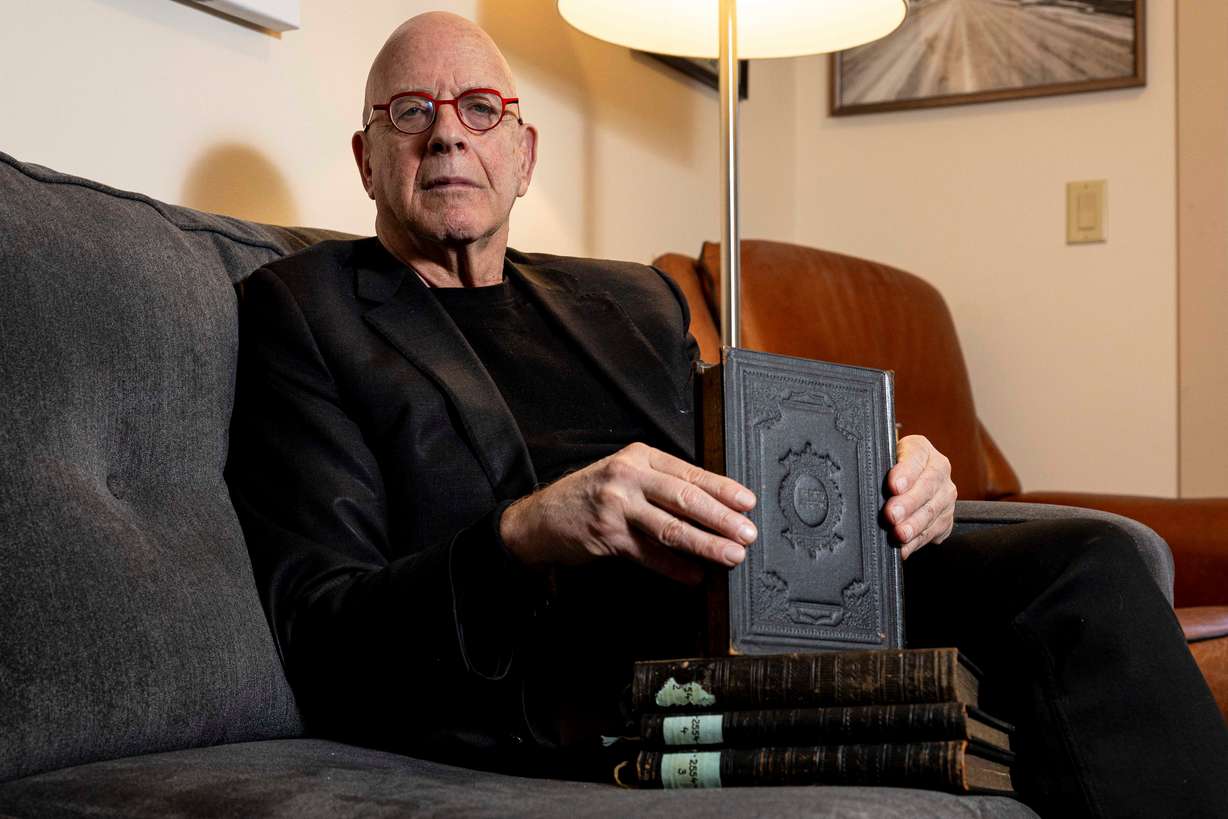

Just last month, Amos Guiora, a University of Utah law professor, received four books that belonged to his grandfather, Shlomo Natan Goldberg, who died at Auschwitz in 1944. The leather-bound volumes that contain explanations and interpretations of Jewish law found in the Talmud were embossed with his grandfather's name in Hebrew.

Guiora, whose Hungarian parents survived the Holocaust but never talked about it, knows little of his grandfather and has never seen his picture. Receiving a tangible link to his ancestors left him overwhelmed and speechless.

Franklin doesn't have to look too far to understand how a book recipient feels because she is the recipient of one herself. Several years ago in Nuremberg she received an Alfred Lord Tennyson book in German that belonged to a cousin.

"It was a wonderful feeling," she said.

But Franklin adds that receiving a book often raises as many questions as it answers. What was my ancestor like? What were her interests? How did he get this book? How did it get from my ancestor's hands to Streicher's library? What was its journey? Who took it? How did it get saved?

The genealogists recently came across a book with an inscription written by a young boy: This prayer book is 200 years old and sometimes I think about what its journey was for the last 200 years and where will it be 100 years from now.

"And 100 years from now, it was returned to his son in 2025," Franklin said.

In your face

Why the Streicher kept books belonging to Jews isn't clear, especially considering the Nazi campaign in the 1930s to burn books that opposed Nazism and later kill all the Jews in Europe.

"In a way, they're spoils of war, proof of the dirty deeds that they did," Franklin said, adding there is story that the Nazis wanted to build a museum of the extinct race to show what they accomplished

"How ironic it is that we have these books now as testimony to their dirty deeds and to the destruction that they wrought and that we can return them now."

Franklin is not only a rewarding project but an "in your face" to those who sought to wipe out Jewish culture and heritage.

"To return these books is a way of defeating those who not only tried to take away lives but also to take away history and connection," she said. "So we're reversing that with the ability to restore all of these things to the descendants of those who perished."