Arthur Blessitt is no longer carrying his cross around the world

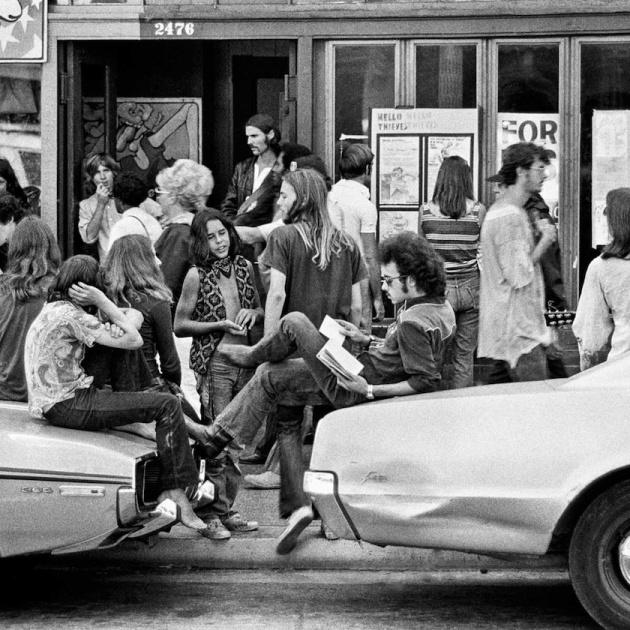

A street preacher, he set out to carry around the world the huge cross that he had hung on the wall of the premises of his mission to the “hippies” of the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles.

17 MARCH 2025 · 09:45 CET

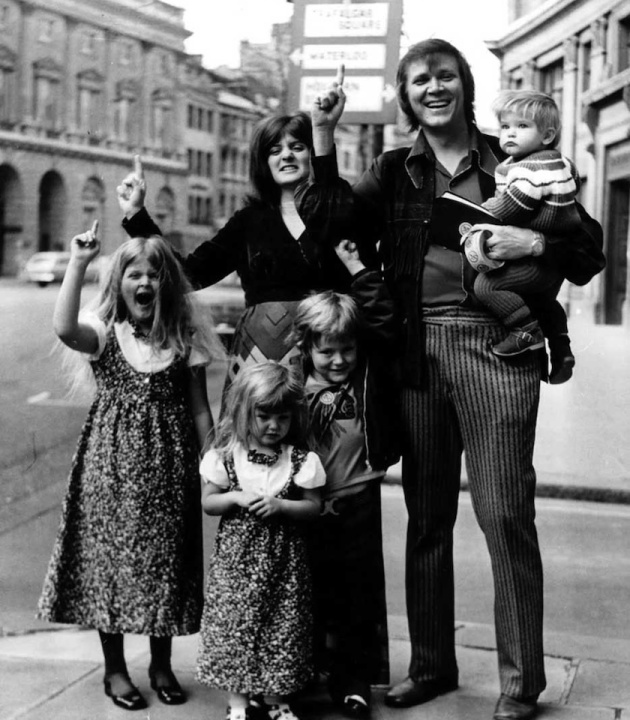

At the age of 84, Arthur Blessitt (1940 –2025) has completed his “walk and mission on earth” after his passing on 14 January. A street preacher, on Christmas Day 1969, he set out to carry around the world the huge cross that he had hung on the wall of the premises of his mission to the “hippies” of the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles.

He was a key figure in the Jesus Movement in England and the United States. In 1972, he travelled to Spain while it was still under dictatorship, and was arrested by Franco’s police. The repression of this act in Madrid’s Plaza Mayor was one of the most publicized examples of Spain’s lack of religious freedom in the foreign press.

In the late summer of 1968, the young people who had gathered in California had to go on with their lives. “The dream was over”. After the “Summer of Love”, most left San Francisco to return to their studies or work, but others sought the warmth of Southern California where the “Jesus Movement” was gathering strength. In the early 1970s, the Movement mainly spread among restless pastors working with young “hippie” evangelists who wanted to reach out to that generation.

The Movement had various foci, but the initiative was now one led by individuals rather than church councils, as in San Francisco, where the first mission had been set up during the “Summer of Love”.

The action was now on the streets of Los Angeles, in Arthur Blessitt’s Sunset Strip mission, in the Salt Company coffeehouse at Don Williams’ Hollywood Presbyterian Church and at Chuck Smith’s Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa.

To this was added the already disturbing presence of the Berg family at the Huntington Beach Light Club coffeehouse and that of the Alamo family in an abandoned restaurant in the Saugus desert, next to the canyon where the Manson Family set up shop.

By this point, the Movement already had several defining features. It was clearly an evangelical movement. It adopted a literal interpretation of Scripture and placed a strong emphasis on the Pentecostal or charismatic experience of the gift of tongues, prophecy and “words of wisdom”.

The Movement’s counter-cultural background made its pessimism even more radical than in the popular dispensational eschatology prevalent in US evangelical circles. But what distinguished it from other evangelical movements was its members’ communitarianism and their marginal lifestyle, far from the mores of traditional bourgeois society, giving a casual feel to their services.

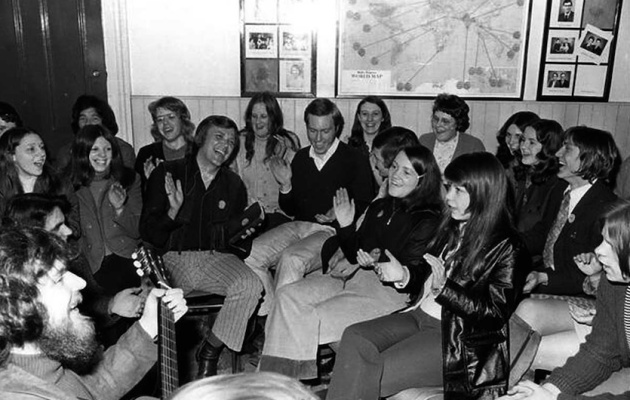

The Movement’s aesthetics changed the work among young people in all churches. The music would never be the same again, but neither would the way of dressing, speaking and relating to one another. Its members witnessed on the street, but it was personal one-to-one evangelism rather than open-air preaching on a street corner, giving invitations to attend a “crusade” or mass evangelistic campaigns.

They had meetings in places that didn’t look like churches, where you didn’t have to dress up in special clothes, which was not at all common in traditional Protestant circles.

Before going to Los Angeles

At first, all these missionary efforts were not aimed at a particular type of youth. They began to take on a counter-cultural flavour as the older pastors let the hippie-looking youth attract others through their witness.

Although kids were drawn in from traditional churches, they did not set the tone. The younger pastors were like sponges, immediately absorbing the way the street talked and dressed, as Philpott did in San Francisco.

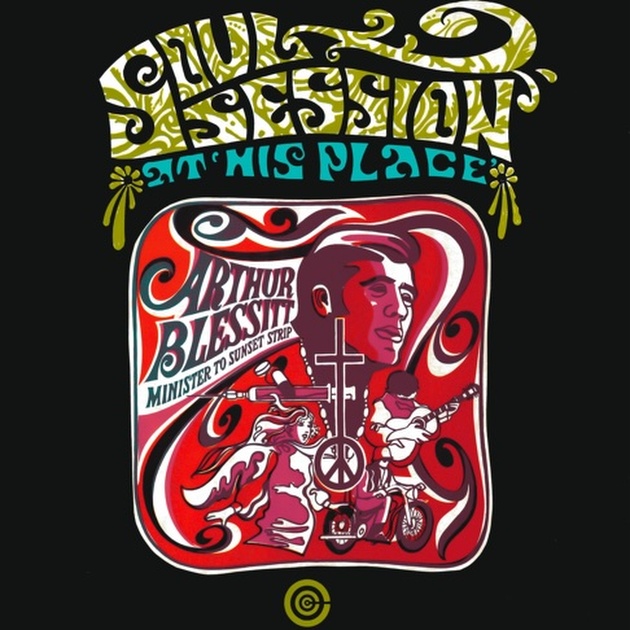

Blessitt spoke of “the trip” and “getting high” with Jesus, using the language of the drug culture. He talked about “dropping” the gospels like LSD or “getting high” with Jesus, twenty-four hours a day, “hallucinating”.

Born in the “Southern Bible Belt” of Greenville, Blessitt grew up among Southern Baptists in Louisiana. His father was an Air Force officer who served in World War II. Arthur went to Clinton Baptist College (Mississippi) and led a youth ministry in small Baptist churches in Brookhaven and Anaconda (Montana), before attending Golden Gate Baptist Seminary in Mill Valley.

Disappointed with the “spiritual coldness” and what he considered “arch-liberalism” of professors and students, he left his theology studies to begin an itinerant ministry around Elko, Nevada.

When he arrived in Southern California in 1967, he tried traditional “revivalist crusades” at a fairground in San Bernardino, but to little avail. It was then that he felt that the Lord was calling him to work among street kids.

The mission on the Sunset Strip began when he went there with his first wife Sherry – he remarried after his divorce in 1990 – to hand out tracts and sandwiches, along with a New Orleans Baptist pastor named Leo Humphrey.

In his 1971 book, Turned On To Jesus, he says that he would at first wear a suit and tie, but that the kids would run away in terror, mistaking him for a narcotics police officer. He then let his hair grow out and took to wearing more youthful clothing.

At first he had nothing more than a rundown motel room on Sunset Boulevard, but in mid-’68 he rented a commercial space at number 9109, between bars, nightclubs and strip joints.

“His Place” on the Sunset Strip

The “His Place” coffeehouse was a large darkened room with flashing coloured lights. Slides were projected on the wall and gospel messages were played twenty-four hours a day.

Everyone drank Kool-Aid – tragically famous for supposedly being the liquid used to dissolve the poison that killed 900 of Jim Jones’ People’s Temple sect in Guyana – and ate peanut butter sandwiches and bagels, made by a Jewish baker the day before. The mission had its own music group, Eternal Rush.

Coupled with the call to pray to receive Jesus was the “bathroom service”, which consisted of being accompanied to the bathroom to throw away all the drugs one had on one’s person. Efforts to keep the place “clean” were not always successful, as in the time someone put LSD in the Kool-Aid and everyone went on an unexpected “trip”.

The drugs were not just “weed” or “acid”, but often amphetamines, known as “reds”. That was what Blessitt called the sticker he designed with the words “Smile, Jesus Loves You”. I

n its original version, it showed a cross and the peace symbol, along with the address of “His Place”. People got fed up of seeing the stickers on traffic lights, lamp posts, traffic signs and all the doors in the area.

It is not surprising that a whole neighbourhood movement rose up against the mission. In the spring of ‘69 it seems that they had already closed down a liquor store and a nightclub, or so Blessitt said.

The police started to stop them in the street, they entered the mission and the owners of neighbouring bars put pressure on the sheriff and the owner of the premises. They looked for a new place, but nobody wanted to rent to them.

This was when Blessitt resorted to dramatics. He erected a cross on the pavement and chained himself to it. He reportedly fasted for 28 days, attracting the attention of the local press and television, until a Jewish businessman offered to lease him a space in his building at 8428 Sunset Boulevard.

The idea of carrying a cross, literally, inspired the initiative that began on Christmas Day 1969 and led him to travel the world.

The man with the cross

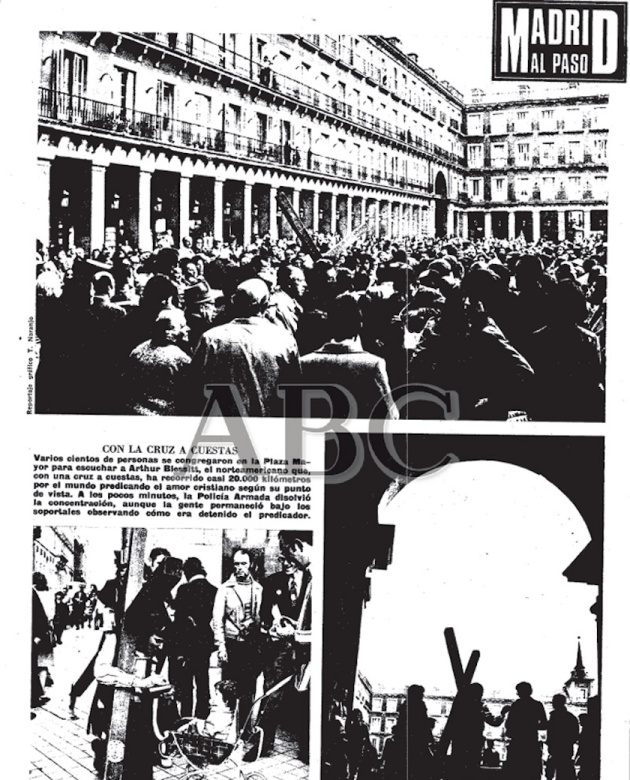

When I was a child, my pastor was called Don Alberto Araujo. He began to introduce elements into our evangelical church that broke with the traditional liturgy. In 1972, he went so far as to embrace the charismatic movement and to invite Arthur Blessitt from his mission on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles to Madrid’s historic main square, the Plaza Mayor.

There, Franco’s police violently repressed the evangelicals – including myself and my parents – who had gathered to listen to him.

I will never forget the image of women and children on their knees, praying and singing hymns, while being beaten by agents on foot and on horseback. The grey police vans had taken over the square and in a few moments the “greys” everywhere, beating everyone up.

I particularly remember one lady lying on the ground with her head bleeding. Blessitt was clutching the huge cross he carried everywhere, while being beaten all over his body, except on his head.

He and Araujo were dragged to the dungeons of the Department of Security for interrogation. A prayer evening was organized at the church where Araujo preached and I went to Sunday school, right in the heart of Madrid. Araujo and Blessit were finally released that night, thanks to the intervention of the American consul.

Araujo had studied theology in the Presbyterian tradition of the Church of Scotland. It was he who interpreted for Blessitt in Madrid’s Plaza Mayor and at the service the next morning in a packed church.

I listened to him on the loudspeakers upstairs. Some time beforehand, Don Alberto had begun to dispense with his gown, which did not go down well with the church members – ever since I was a child I have observed that there is often a curious attachment between theological liberals and clerical garb.

I remember one Sunday, in particular, when Don Alberto called all the children to sit on the front steps and showed us the famous “Wanted” poster, popularized by the “hippie” movement, with the image of Jesus as an outlaw from the Wild West.

Crazy for Jesus

There was an obvious eccentricity in someone like Blessitt, but the same could be said for my pastor. He was capable of doing anything in his “madness for the Kingdom”. Many of us now feel nostalgic for those Revival years.

There was something spontaneous and unpredictable that always surprised you, but there was also a lot of chaos and naivety. I recently listened to an interview with Philpott, another man of conviction, who embraced the charismatic experience as enthusiastically as he rejected it ten years later, and is now the pastor of the Reformed Baptist church where the first “hippies” converted in San Francisco.

He says at one point in the interview that “the Jesus Movement was not clean”. What he meant was that when many pastors approached him out of curiosity or tried to use him, they were “tainted” by him, not in the sense of corruption, but of confusion.

In order to write my unfinished series on the Jesus Revolution, I listened to many hours of recordings by Larry Eskridge – who has published research on the Jesus People Movement with Oxford University – held at the Wheaton Evangelical College archive.

Some of those he interviews, such as Ted Wise and Arthur Blessitt, are no longer with us. I would have liked to meet Wise. He was not only a pioneer in San Francisco, but also one of the most intelligent and skilful leaders the Movement had in its early days.

Unlike Philpott, Wise never had the Pentecostal experience. In the late 1960s, he joined a church along Brethren lines, Peninsula Bible Church in Palo Alto, pastored by Ray Stedman, known for his expository preaching of the whole Bible – like MacArthur, but without all his quirks and prejudices.

It makes you wonder where the Movement would have gone if they had got rid of both charismatic prophetic extremism and conservative fundamentalist legalism. Either way, there was a genuine spiritual awakening among young people, as well as many false conversions.

One of the mistakes that both Philpott and Wise recognized was that they tended to separate themselves from the churches. There was a certain pride, says Philpott, in the belief that they were in “the moving of the Spirit”, unlike the others.

Now he sees it as real pride. Wise says something in the interview that really struck me. He was not a great preacher, but he had a lot of influence on people. He could, like Philpott, have become a charismatic leader, but he realized he had only two options: “Either you join a church, or you promote yourself”.

He found the former much healthier. The latter is what many in the evangelical world are still engaged in. It is full of self-absorbed individuals who have no shortage of hopes and dreams, but who confuse building their own empire with building the Kingdom of God.

No one doubts Blessitt’s eccentricity, but “madmen” like him have done great things for Jesus. Two books tell his story: The Cross: 38,102 Miles, 38 Years, One Mission (2008) and A Walk with the Cross (1978), as well as a documentary, The Cross (2009).

His accounts often have exaggerations and inaccuracies, but they come more from his difficulty in differentiating his spiritual impressions from the reality of what happened.

There is no doubt that God used him powerfully for the conversion of many people. And it is clear that his adventure was miraculous.

In 2000, a journalist spoke to him in Cape Cod and asked him how his feet were doing after walking all over the world. He took off his shoes to show her that he had “no bunions, no pain”. That was a miracle in itself!

José de Segovia, journalist and evangelical pastor in Madrid, Spain.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Arthur Blessitt is no longer carrying his cross around the world