Periyar, Tamil and ‘barbaric’ label: Reading between the lines

The rationalist and founder of the self-respect movement was critical of the language, but at other times, crucial to its evolution and growth. Can he be bracketed without context?

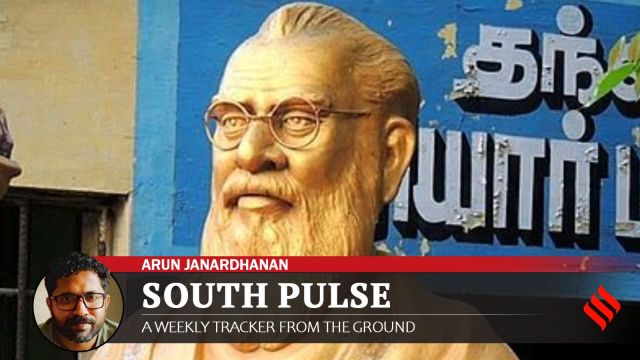

Periyar did refer to Tamil as “a barbarian language”, but it was because of his belief that it had “not evolved or reformed” over time. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Periyar did refer to Tamil as “a barbarian language”, but it was because of his belief that it had “not evolved or reformed” over time. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)DURING the heated discussion in Parliament last week over the National Education Policy (NEP), with the DMK claiming “forcible imposition of Hindi”, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman hit back saying that while the DMK attacks the BJP, it reveres the person who once called Tamil “a barbaric language”.

The reference was to Periyar, the founder of the self-respect movement out of which the Dravidian political ideology was born, and one of the greatest rationalists and social reformers of Tamil Nadu.

The DMK reacted with outrage, saying Sitharaman’s remarks were reflective of the BJP’s stand and insulted the Tamil nationalist sentiment.

But what did Periyar say about Tamil, and in what context?

* Self-respect vs linguistic pride

The social reformer did refer to Tamil as “a barbarian language”, but it was because of his belief that it had “not evolved or reformed” over time, “clinging to ancient glories” without adapting to modern needs.

As a proponent of the self-respect movement who spoke of human welfare above all else, Periyar rejected linguistic nationalism or pride – as he did any affiliation with race, religion or caste. Hence, the focus of Tamil scholars on Bhakti literature and ancient traditions which perpetuated caste and superstition was attacked by Periyar, who chose a blunt, provocative approach deliberately, to best catch people’s attention.

In December 1970, in a piece in the Viduthalai daily, Periyar put this in his own words: “I bear no personal animosity towards Tamil. My concern is that Tamil has not evolved to meet the demands of a modern language, particularly in conveying scientific knowledge. In contrast, English is rich in science and knowledge. This disparity troubles me.”

Periyar’s writings up to 1949 reflect his push for Tamil to be used as a tool for transformation, equality and dignity. This was in tune with the realities of the time, with caste discrimination at its peak, with linguistic purism seen by Periyar as a part of that.

The DMK incidentally was founded only in 1949, and its embrace of Tamil as a part of Dravidian identity and pride followed after that.

Periyar also led the fight against Kula Kalvi Thittam, the Hereditary Education Policy of the early 1950s, often seen as Tamil Nadu’s first “NEP encounter”. It called upon students to learn their parents’ trades, such as farming or as barbers, entrenching caste-based inequality.

* Periyar’s Tamil push vs Sanskrit

Periyar who kept his own organisation, Dravidar Kazhagam (DK), away from electoral politics, moderated his views over time. For example, he criticised the classic Tamil text Thirukkural but later also promoted its reformist aspects.

During the first anti-Hindi movement in the 1930s, Periyar mobilised Tamil scholars.

His fight against Sanskrit – and, by extension, upper caste – hegemony, also led him to back Tamil. When the University of Madras was founded in 1857, under the British, it didn’t have a Tamil department. When a Tamil department was established 70 years later, in 1927, Brahmin groups protested, demanding Sanskrit’s supremacy. In the university’s Madras Christian College, Tamil was taught as a minor subject. Tamil scholar Maraimalai Adigal, the leader of Tanittamil Iyakkam (Pure Tamil Movement), had to quit the college after Tamil was removed as a second language by the University of Madras.

Periyar met Adigal and supported him financially. Periyar’s agitation also played a key role in abolishing Sanskrit as a requirement for university and medical admission.

Similarly, Periyar organised state-wide protests against the practice of ‘Brahmin hotels’, which were common till the 1960s. Gopalan Ravindran’s book Spatialities, Materialities, and Communication in South India writes about a protest against Murali Café in Mylapore led by Periyar’s aide M Gopalan that lasted months.

Among those Periyar held in high regard was Vallalar, the 19th-century Tamil Shaivite saint, who challenged Sanskrit and was an early proponent of Tamil identity. Periyar’s first edition of Kudiyarasu, his political mouthpiece, in 1927 prominently featured Vallalar’s verses.

His insistence on Tamil in public discourse left a lasting mark. For example, the replacement of the word prasangam with sorpazhivu for speech. Similarly, he promoted the use of Vanakkam over Namaskaram as a greeting – Prime Minister Narendra Modi now uses the same in his Tamil Nadu speeches.

When Dravidian parties came to power, they pushed to de-Sanskritise Tamil Nadu’s map. Mayuram, meaning ‘peacock town’ in Sanskrit, hence became Mayiladuthurai in 1982. Many Dravidian leaders also changed their Sanskrit names – V R Nedunchezhiyan (changed from Narayanaswamy), K Anbazhagan (formerly Ramaiah), and K Veeramani (Sarangapani).

* Revival of Tamil

For Tamil to get its place in governance and public life, Periyar pushed for reviving it as a modern language, by seeking to simplify its script for typing and printing, and pushing for reducing the number of letters used and dropping redundant signs.

In 1978-79, the MGR-led AIADMK government adopted some of these reforms and standardised syllables to enhance accessibility, aligning with Periyar’s vision.

Sitharaman’s remarks reflect a common misreading of Periyar, says Kali Poongundran, a close aide of Periyar and the vice-president of the Dravidar Kazhagam. “His critique of Tamil came from frustration – to remind people that linguistic pride alone wouldn’t uplift the oppressed… Periyar knew language alone wouldn’t break oppression. His real fight was against Brahminical dominance in religion, governance, and education. Tamil was one front in a larger war.”

Interestingly, given the language debate currently on, Poongundran says Periyar was all for learning English. “He even urged people to speak English at home to climb the social ladder… His argument that Tamil alone cannot ensure social mobility remains relevant today,” Poongundran says.

Must Read

Buzzing Now

Mar 20: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05