Jose Mario O. Mandia

In the Basilica of Saint Paul’s Outside the Walls in Rome, one can find a series of mosaic portraits of the popes from Saint Peter all the way to Pope Francis. The project began with Pope Leo the Great (440-461) but a fire destroyed the Basilica in 1823. Only 40 portraits were saved. In 1847, Pope Pius IX (1846-76) revived the project which, of course, is ongoing.

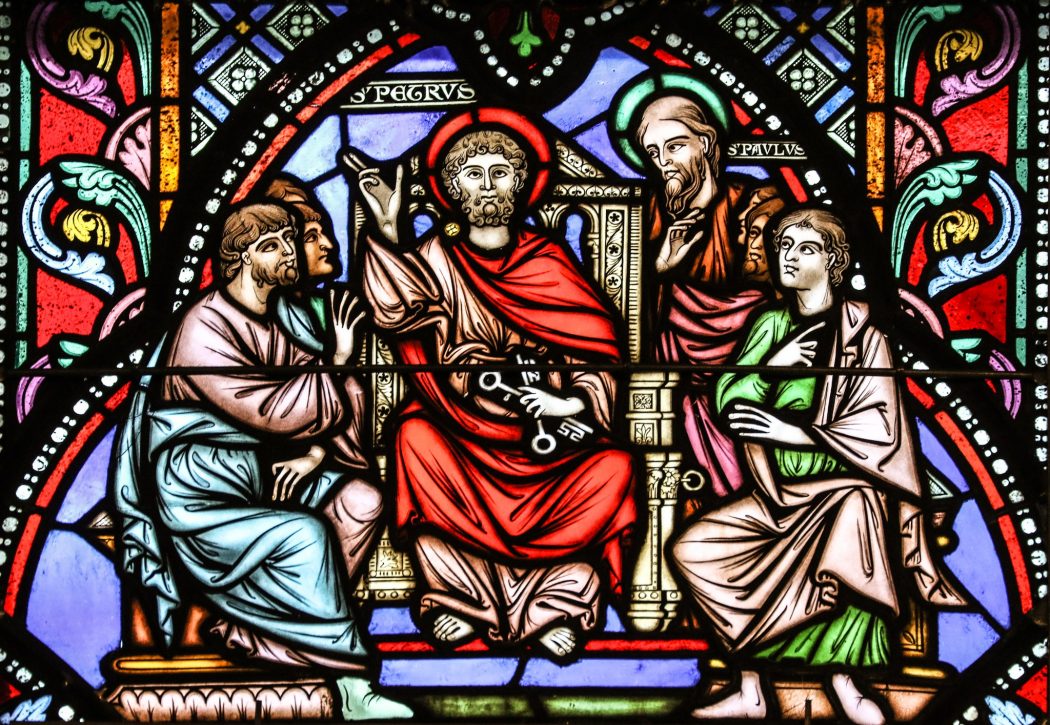

One of the questions that is often asked is how the Popes are chosen. St Irenaeus (130-202) reports that the first successor to Peter, St Linus, was chosen by Saints Peter and Paul themselves (cf Against Heresies III.3.3). Many scholars record Linus as being Bishop of Rome from 68 to 80 AD.

Nowadays, the Pope is chosen during a Conclave, a closed-door election through secret ballot, by cardinals from all over the world. But in the beginning, the Church was still small, and we can presume that the Successor to Peter would be chosen by a group of bishops, priests and, perhaps, even some lay persons. Some scholars think that the laity were included only after the time of Pope St Sylvester (314-335 AD). It also seems that unanimity was required in the early papal elections.

The Church suffered persecution until Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313 AD. The imperial decree gave Christians the freedom to practice their faith. This obviously brought many benefits to the Church, but it also opened the way for the interference of civil authority in Church governance.

“An epoch-making decree in the matter of papal elections is that of Nicholas II in 1059. According to this constitution, the cardinal bishops are first to meet and discuss the candidates for the papacy and select the names of the most worthy. They are then to summon the other cardinals and, together with them, proceed to an election. Finally, the assent of the rest of the clergy and the laity to the result of the suffrage is to be sought. The choice is to be made from the Roman Clergy, unless a fit candidate cannot be found among them. In the election regard is to be had for the rights of the Holy Roman emperor, who in turn is to be requested to show similar respect for the Apostolic See. In case the election cannot be held in Rome, it can validly be held elsewhere. What the imperial rights are is not explicitly stated in the decree, but it seems plain from contemporary evidence that they require the results of the election to be forwarded to the emperor by letter or messenger, in order that he may assure himself of the validity of the election. Gregory VII (1073), however, was the last pope who asked for imperial confirmation” (Fanning, W. (1911). “Papal Elections.” In The Catholic Encyclopedia. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11456a.htm)

Papal elections were not always smooth and sometimes could take months or even years! “To prevent a recurrence of this evil, the Second Council of Lyons under [Blessed] Gregory X (1274) decreed [in Ubi periculum majus] that ten days after the pope’s decease, the cardinals should assemble in the palace in the city in which the pope died, and there hold their electoral meetings, entirely shut out from all outside influences. If they did not come to an agreement on a candidate in three days, their victuals were to be lessened, and after a further delay of five days, the food supply was to be still further restricted. This is the origin of conclaves” (Fanning, W. (1911). “Papal Elections.” In The Catholic Encyclopedia. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11456a.htm) The term ‘conclave’ comes from Latin cum clave (‘with a key’).

As the years passed, the rules governing conclaves were further refined and adjusted. The most recent of the decrees setting these rules were issued by Pope Pius XII (Vacantis Apostolicae Sedis in 1945), Pope John XXIII (Summi Pontificis electio in 1962), Pope Paul VI (Romano Pontifici eligendo in 1975), John Paul II (Universi Dominici Gregis in 1996, amended by Benedict XVI in 2007 and 2013).

Follow

Follow