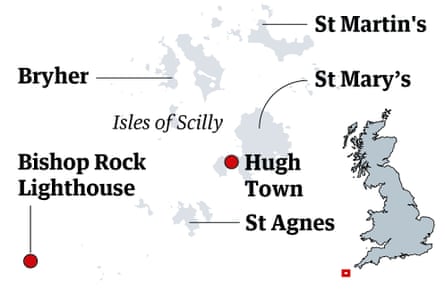

Of all the striking scenes that the Isles of Scilly offer – from beaches that look too tropical to be in Britain to wild boulder-strewn headlands and the magical Abbey Gardens – the one that lodged in my mind was Bishop Rock lighthouse. Writers and painters the world over have been drawn to the dramatic potential of lighthouses, but Bishop Rock is special. It watches over one of the most treacherous stretches of British coast, four miles from the nearest inhabited island, and was finally completed, on its tiny mound of rock, in 1858, after a previous attempt was swept away. (It was further strengthened in 1887.) On nearby rocky Rosevear lie the ruins of a cottage where the workers who built it lived, rowing out to the site with giant blocks of granite that had been cut and rounded on St Mary’s quay. Incredibly, no lives were lost in its construction.

From the most southerly of the Scillies, St Agnes, my 10-year-old son and I joined a sealife safari on board catamaran the Spirit of St Agnes. Sailing west past uninhabited Annet island, a renowned seabird site, to the notorious Western Rocks, site of many a shipwreck, we clocked up an impressive tally of wildlife: Atlantic grey seals; porpoises; a fulmar and its chick, well camouflaged against a rock; and, most excitingly, a bizarre sun fish, flapping its dorsal fin back and forth. Basking sharks and swordfish have been spotted here too, drawn by the deep, plankton-rich waters.

At first the lighthouse appeared no bigger than my finger, a miniature tower surrounded by grey sea and sky. As we drew closer I spotted windows and a door halfway up the tower, with a ladder running up to it like a scar on a creepy face. Every month, lighthouse keepers would change shifts, new arrivals being winched up to enter the tower. Until 1976, when a helipad was installed, supplies were also delivered by boat – a treacherous job in itself. Today, decades after the last keepers left, Bishop Rock seems a fitting symbol for the islands – speaking of ingenuity, determination and survival.

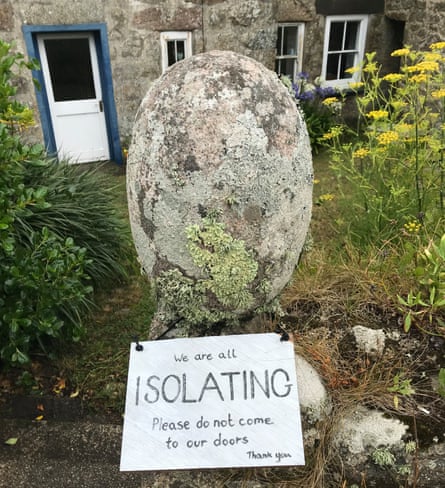

During lockdown on the islands, these characteristics shone through. All but essential transport was stopped from the mainland and between islands, which were subject to the same strict rules as the rest of the UK, despite the fact that there wasn’t a single case of coronavirus in the Scillies.

“Lockdown was bizarre,” said Amelia Mills, who runs The Sailing Centre, on the largest island, St Mary’s. “We had this amazing weather and kept expecting to see tourists, but it was completely empty. We weren’t allowed on the water, either – it was heartbreaking.” For Jason Poat of Polreath Tea Room and Guest House on St Martin’s, further north, lockdown felt like “winter with sunshine”. “The winters are so quiet here I joke that I’ve been training for lockdown for 20 years.”

Hunkering down kept everyone safe – there have still been no recorded cases, but the timing was devastating. March is the start of the tourist season. No visitors meant no income. “You could lose 20 years’ savings in one year in this situation,” said Poat. Despite the desperate need to restart tourism, the 4 July reopening was met with trepidation. “I’m torn: if I don’t work there is no money, but when you live on an island of 100 people, about a quarter of whom probably fall into the vulnerable category, you know you are taking a risk.”

Arriving from London, where social distancing in local shops and green spaces is observed patchily, I sensed the nervousness. Shopkeepers were strict about hand sanitising; masks were mandatory on all inter-island boats, even though we were in open air; there was always a queue outside the Co-op, the island’s only supermarket. Walking around the narrow lanes of St Agnes, the most south-westerly inhabited point of the British isles, population 85, we spotted several signs outside homes saying: “We are all isolating. Please do not come to our doors.”

Yet none of this detracted from the beauty of the islands. They are saturated with gorgeousness. Every time we walked from Garrison campsite, named after the defensive walls that used to surround this part of St Mary’s, the view of the harbour stopped me in my tracks. My son berated me for taking so many photos. I would put my phone away, only to get it out minutes later to snap the next beach or bay.

We based ourselves on St Mary’s, camping for a week – reduced capacity meant there was no problem social distancing – and spending the last three nights at Wingletang Guesthouse in Hugh Town.

On our first day, I persuaded my son to walk “all the way” (10 minutes) to Porthmellon, a curve of white sand bookended with granite boulders, with a sheltered bay perfect for first-time paddleboarders, windsurfers and kayakers, on gear rented from the Sailing Centre overlooking the beach. Those who’ve had plenty of practice can board between islands, but as beginners we stuck to the bay – and trying not to fall off.

Another day we hired bikes to explore St Mary’s further, heading to Pelistry beach on the east coast – another sheltered cove with an islet, Tolls Island, accessible at low tide. It was hard not to feel smug at the sight of just two other families on the sand – this was the week when the news was full of images of rammed beaches on the mainland. I had been disappointed that a snorkelling with seals experience on St Martin’s was sold out until September, but at Pelistry I got the chance to swim with a seal for free after I noticed a sleek head popping out of the water. I got within about 10 metres of its whiskery face before deciding that was close enough. A braver swimmer later described seeing several seals making figures of eight over the seaweed forest below.

Stopping at the first gorgeous beach we saw became the norm. On St Martin’s I had every intention of heading to Great Bay, but missed the turning and ended up on Par beach instead. Anywhere else in the UK, Par’s white sand and clear water would put it in a top 10, but the bar is set high in the Scillies. On tiny Bryher we meant to seek out Rushy Bay, recommended by Amelia at the Sailing Centre. Instead we walked straight off the boat into the cafe at Island Fish, ordered potted crab and crab claws and plonked ourselves on the white sand next to the jetty. The sea was gin clear with barely a ripple; to our left we could see Cromwell’s castle on Tresco, one of the many views captured by artists over the centuries.

Today the islands have their own thriving community of local artists. Hayden Simpson’s bright paintings are on display at On the Quay, an industrial-style restaurant in Hugh Town run by a Leicestershire couple who saw a gap on the islands for a something beyond cream teas and pub grub. Now you can order bistro-style food and cocktails while watching the boats come and go on the quay. My potted shrimp, filled with applewood smoke, and scallops on celeriac puree was the best meal of my trip. On St Martin’s, jeweller Fay Page sells gold and silver pieces inspired by the sea and local wildlife from her studio in a listed stone building (closed, though online orders can be collected via a hatch). Artist Inga Drazniece was the driving force behind Middletown Barn – a tiny co-operative gallery showcasing St Martin’s makers. Among them is Ella McLachlan, who recently established Phoenix and Providence, a skincare collection produced using kelp collected on St Martin’s beaches.

Another artist, Chris Hanky, was working a season at the Garrison campsite and painting between shifts. Outside his tent were two big oil paintings of stormy skies and seas. These are scenes summer visitors rarely witness, but for Hanky the islands are at their most mesmerising when battered by the elements. As we talked a hedgehog emerged, reminding me of another artwork we’d spotted – a new decorative window at a seafront shelter in Hugh Town designed by eight artists and depicting scenes of island life, including the gigs once used to pilot ships safely into harbour, and the Scillonian ferry, which is celebrating its 100th anniversary.

The project was coordinated by Oriel Hicks, a stained-glass artist who married a Scillonian and moved here in 1991. She set up Phoenix Craft Studios near Porthmellon beach, sharing with artists including one who makes shoulder bags out of pairs of shorts that were part of the cargo from a container ship wrecked on St Mary’s in 1997. “There were containers full of wood, too,” said Oriel. “There was so much of it that people were fixing their boats with really good-quality teak. I got a parquet floor, and half the people I know have doors in their houses from the ship.”

Bags made from shorts and boats fixed up with a surprise arrival of teak are classic Scilly – repurposing is in the blood. Ratbags, a successful canvas bag business on St Mary’s, originally used offcuts from its sailmaking arm. They were so popular the family upped its range and now produce bags in many shapes and sizes. On St Agnes we met Emma Eberlein, owner of the Pot Buoys Gallery. Her repurposing takes the form of jewellery made from plastic found on the beaches – of which there is, thankfully, less and less – “great for the environment but not so much for my art”.

Visitors to St Agnes might be lucky enough to find their own treasure. Beady Pool is so called because beads from a 17th-century shipwreck were once regularly found on it. Occasionally they are still spotted. Wingletang’s owner, Jacqui Ramsden, had shown me some of the little red clay beads she had found there. We had no such luck, but just visiting St Agnes is enough of a treat. I walked from Beady Pool onto the clifftop, where boulders form natural sculptures. I could see St Agnes’s own little lighthouse, built in 1680, in the distance, and the bay’s white curve of sand, but other than that there was nothing but sea and rocks and wildflowers. It was a moment to forget about the upheaval of coronavirus and revel in timelessness and endurance.