SoCal Drafted Its Buildings To Help Win WWII — And We're Doing It Again To Fight Coronavirus

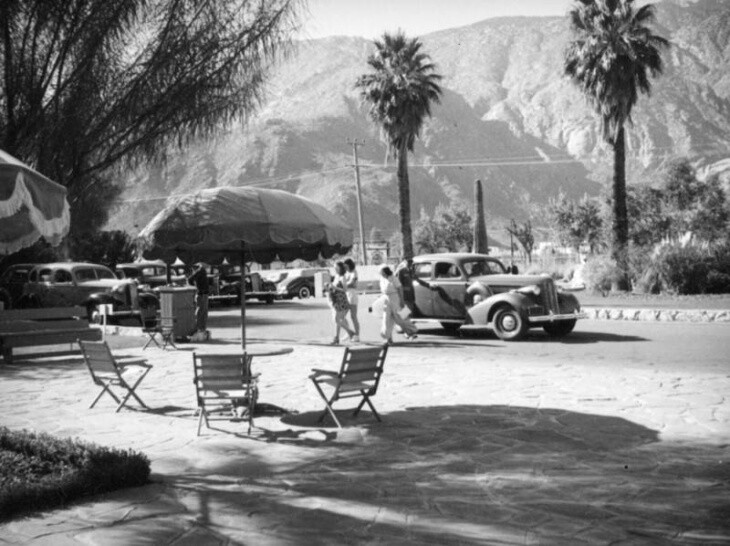

It was another glorious Palm Springs day in the fall of 1943. On the grounds of a sprawling Spanish Revival compound, the sun was shining on an idyllic scene.

"Lawns are being sprinkled and cut. The border beds are freshly planted with flower cuttings and give promise of color in another month. The pool is open all day... Men in maroon bathrobes and pajamas sit in deck chairs chatting with visitors," the Los Angeles Times reported.

But this was no typical Palm Springs five-star resort, at least not any more. The El Mirador Hotel, once populated with celebrities and society mavens, had been transformed by the United States government into the Torney General Hospital. The men in maroon bathrobes weren't café society dilettantes. They were soldiers recuperating from injuries sustained in battle.

During World War II, hundreds of buildings across Southern California were drafted into service for Uncle Sam. Today, we're doing much the same thing to fight the coronavirus pandemic. The L.A. Convention Center and Sheraton Fairplex in Pomona have been transformed into field hospitals and COVID-19 testing centers while some local hotels have become hostels for homeless people. It echoes the Southland's history of responding to crises. WWII wasn't the first time the region encountered life-altering events that required the emergency repurposing of buildings.

According to historian Mark Landis, author of Arrowhead Springs, California's Ideal Resort, in 1920, Arrowhead Springs, a lush resort in San Bernardino, was briefly leased by the Army for use as a convalescent hospital for WWI veterans.

The St. Francis Dam disaster of March 13, 1928, resulted in a flood that spread from the Valencia area to the beaches of Ventura, killing hundreds. According to Santa Clarita Valley History, buildings (including Hap-A-Lan Dance Hall in Newhall) had to be converted to morgues while the flood raged.

In the aftermath of the 6.4 magnitude Long Beach earthquake on March 10, 1933, churches and parking lots became makeshift hospitals, helping people after local hospitals were destroyed or damaged.

But it was World War II, fought in Europe and the Pacific, that most drastically, although temporarily, transformed L.A.'s footprint.

According to historian Mike Eberts, author of Griffith Park: A Centennial History, the sprawling park would be home to a camp that processed Japanese American, German and Italian detainees. Soldiers camped near the Greek Theater, swimming in the park's pool and learning about celestial navigation at the observatory.

After the war, the Rodger Young Village, a camp of 750 Quonset huts near the current site of the Autry Museum, provided homes for returning soldiers and their families from 1946 to 1953.

On a much darker note, Griffith Park wasn't the only place used to process Japanese American detainees. Both the Santa Anita Racetrack and the Los Angeles County Fairground in Pomona were used as temporary holding centers for Japanese Americans before they were sent to internment camps at Manzanar, Heart Mountain and Tule Lake. At Santa Anita, families had to live in converted horse stalls.

During the war, finding lodgings for soldiers waiting to be shipped overseas was a pressing concern. Famous hotels like the Biltmore and the Beverly Hills Hotel housed soldiers and USO centers. According to the Santa Monica Daily Press, local beachside hotels including the Fairmont-Miramar, the Shangri-La and the Casa del Mar became temporary dorms (formally known as redistribution centers) for soldierz. Recreation and hobby centers were opened in the hotels, and the pools welcomed all service members free of charge.

The unlikeliest of places became part of the war effort. The Los Angeles County Poor Farm in Downey, home to L.A.'s indigent and infirm, became an emergency hospital. Part of the land was also turned into a soldier's camp called Camp Morrow, and a rubber factory was opened to aid the war effort.

At least one prominent private residence was also drafted into use. At the famous Adamson House in Malibu, the Coast Guard watched the ocean from the bathhouse and grounds of the property.

Grand hotels faced the greatest overhauls. With their hundreds of bedrooms, large dining areas and spacious grounds, they could be easily transformed into hospitals for thousands of soldiers who had been wounded while fighting in the Pacific.

The sprawling 53-acre Lake Norconian Club, north of Corona in Riverside County, was the first such establishment be conscripted in the L.A. area, according to KCET'S Sandi Hemmerlein.

Built in 1929, it was designed by L.A. architect Dwight Gibbs in an opulent take on the Spanish Revival style. The hotel featured an elaborate lakeside pavilion, a large dining room, four swimming pools, natural sulphur springs and an airstrip. Sports stars adored the lush golf course and numerous movies were filmed in the scenic spot, including Their Own Desire, a twisty romance starring Norma Shearer and Robert Montgomery.

Hollywood denizens often came down to the hotel for weekend revels.

"In 1938, after making Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Disney threw a cast party that became the stuff of legend. Apparently, Walt Disney was 'mortified' at his employees' shenanigans at that event... 'Skinny-dipping and all,'" Cecilia Rasmussen writes.

The Lake Norconian Club's heyday was short-lived. It fell on hard times by the late 1930s and closed in 1940 but found its second wind in December 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. That's when owner Rex B. Clark deeded the hotel to the Navy in a gesture both patriotic and practical. He was hoping for a $2 million tax return that never came, leading to a lawsuit.

By early 1942, the Norconian had been transformed into a first-rate Naval Hospital. Architect Claud Beelman was hired to add facilities that matched the main hotel's design. The first servicemen transferred to the hospital were 100 victims of the Pearl Harbor attack.

"The heroes of Pearl Harbor find life as easy and luxurious as though they were members of a high-toned country club," the Los Angeles Times reported.

Many of these men had suffered leg injuries so ramps were added. The large pool, which had been used for the 1932 L.A. Olympics, was turned into a rehabilitation center.

The naval theme extended through all aspects of life at the Norconian. "On the ship that never sails, the patients, the doctors and the nurses talk ship jargon. All 'hands' eat in the 'galley' which is the enormous Spanish dining hall. One goes ashore or comes aboard, not leaves or enters the hospital. The shifts of attendants are called watches and so on," the Los Angeles Times reported.

One writer commented on the remarkably pleasant scene:

"In a pocket of the California mountains 50 miles east by a little south of Los Angeles, there is a ship that never sails. It is a ship with a Spanish tile roof and the general contours of what is called mission architecture. It floats in a green ocean of grass and trees- rising and falling seas of sierra foothills. The crew of this ship are badly injured men, young ones for the most part, but they carry on in the traditions of the American navy with many a cheery word and seldom a beef."

A more nuanced scene unfolded at the Vista Del Arroyo Hotel in Pasadena. According to Brain Alan Baker of Pasadena Heritage, the Arroyo Vista Guest House was first opened in 1882 by Emma Bangs. Over the years, Pasadena's fame as a wealthy, healthy haven for the sick and famous grew, and the Vista Del Arroyo became one of the most prestigious hotels in the Southland.

"H.O. Comstock acquired the Vista Del Arroyo in 1930 and expanded the main hotel into the towered, six-story structure seen today, designed by relatively unknown L.A. architect George H. Wiemeyer," Baker says. "The hotel sported 400 guest rooms, including grand suites with up to five bedrooms and four baths, fireplaces and kitchens. The accommodations were described as 'the last word in such matters.'"

The Vista Del Arroyo survived the Great Depression and was one of the hot spots for café society in L.A. County. Pasadena resident Olga Rose recalled to the Times that she "used to go to tea dances there, and the huge, plush old hotel was pale green and rose colored."

All that changed on February 2, 1943. The day started out like any other at the hotel overlooking the famous Colorado Street Bridge but the Army had other plans. That day, by court order, supported by the War Powers Act of 1941, the government took control of the hotel. The 200 guests received individual notices to immediately vacate the premises. Management was given a few days to leave although the Army began moving in the next day.

Soon, the Vista Del Arroyo was renamed the McCornack Army Hospital, after Brigadier General Condon C. McCornack. Olga Rose, who had once flitted about the halls as a Pasadena socialite, now worked at the hospital's makeshift library.

She recalled the scene to the Los Angeles Times decades later:

"She remembers the Australians who were brought there after their ship was torpedoed 25 miles off Long Beach. She remembers the lost frightened men from the Smokies and the Cascade Range and the deep woods of Tennessee who were abruptly thrust into the modern, clangorous age and fierce warfare after being drafted and who couldn't cope. She remembers the scion of a wealthy owner of clothing stores who spent the war wandering the hospital corridors in bathrobe and slippers with nothing apparently wrong with him."

Rose did what she could to comfort the service members in her care. She arranged for movie stars Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth to visit the troops and started a political discussion group. To help a private suffering from trauma (what we might now call PTSD), Rose gave him painting supplies so he could explore his feelings through art. The job eventually became too much for her. After two years, she resigned due to nervous exhaustion.

The most famous Southern California hotel transformation was the El Mirador Hotel and Bungalows in Palm Springs, which had opened New Year's Eve, 1927.

The Spanish Revival hotel, designed by the firm of Walker and Eisen, featured a distinctive bell tower referred to as the "tower of the stars." From day one, Hollywood luminaries such as Gracie Allen, Shirley Temple, Ralph Bellamy, Douglas Fairbanks, Clark Gable, Marlene Dietrich, Carole Lombard and Gary Cooper frequented the establishment. Esther Williams swam in the Olympic pool.

The hotel was still going strong in 1940. An ad placed in the Los Angeles Times that year extolled its many charms:

"The magic of desert life, where rest is play and play is rest, awaits guests at El Mirador Hotel... Acres of color rich gardens appeal to the leisurely, while those more strenuous enjoy the pool, pinto pony riding on the trails, tennis on championship courts, golf, breakfast or moonlight rides. The Coral Room, a new cocktail lounge and private dining room... features famous orchestras and entertainers. All rooms are steam heated, many have fireplaces and private sun porches."

In 1942, the Army bought El Mirador for $450,000. "The best is none too good for the American soldier," one Army officer told the L.A. Times.

Many believed El Mirador's warm, dry desert air was therapeutic for those suffering from chronic lung and respiratory ailments. It was transformed into Torney General Hospital, and named for Brigadier General George H. Torney, former Surgeon General of the U.S.

Administrators crammed 1,500 beds into the hotel's hallways, ballrooms and guest rooms. Many service members taken there were from troops under the command of general George Patton, a Los Angele native.

In 1943, the Los Angeles Times reported:

"When you get a pass, you must be cleared through the provost marshal's office, which is the old caddy house. You present your credentials to a sentry at the driveway, for the grounds are now enclosed with a high wire fence. The lobby has long since been stripped of its bridge and bingo tables and deep armchairs. In their place are rows of steel desks, where men in uniform are working. The fashionable shop at one of the buildings is now the personnel office and instead of racks of clothes there are dozens of steel files. The arch to what was the dining room has been closed, and on a hard bench in front of it, visitors wait for appointments. The mess halls are in the old dining rooms. The blue leather and pink damask chairs are still in use. So is the flowered El Mirador china, augmented with cups and saucers bearing the Army Medical Corps insignia."

Another Hollywood hot spot conscripted into service was the Arrowhead Springs Hotel, the fourth and largest resort in the same location. Opened in 1939 on this scenic spot, 2,000-feet above sea level at the base of the San Bernardino Mountains, the Georgian-style incarnation was owned by a collection of entertainment industry heavy hitters including Joseph M. Schenck, Darryl Zanuck, William Goetz and movie star Constance Bennett. Dubbed the "world's most spectacular resort," it boasted bowling greens, steam caves, mud baths, massage rooms, theater, archery, bridle trails and a famous natural hot spring with "radioactive waters."

In May 1944, Arrowhead Springs was formally transformed into a Naval hospital. "Capt. Joseph A. Biello, a veteran of 37 years of naval service, read orders designating him as medical officer in command. He asked the co-operation of civilians in helping convalescent men 'overcome the unpleasant realities of illness or injury.'... With the hoisting of the colors and the Geneva cross, which designates a hospital, the commissioning ceremony was complete," the L.A. Times reported.

That same week, 500 service members entered the hospital as patients. They were overseen by a bevy of naval nurses, who often participated in swimming contests, much to the delight of recovering soldiers. According to the Times:

"They are making daily use of the pool of the former luxurious hotel even now when snow glistens on nearby mountains... Table tennis and shuffleboard equipment is also available for the nurses and many of them enjoy tennis, golf and riding on the grounds which surround the hospital. Two of the most popular games are bridge and gin rummy which the navy women play often on the lawn... The various recreation outlets have been found effective in keeping the navy nurses physically fit for their arduous tasks in assisting wounded and sick navy men back to health."

Overall, 6,000 service members would recuperate at the Arrowhead Springs Naval Hospital.

After World War II ended in 1945, most of the buildings drafted into service returned to their intended functions. This was not the case for the resort hotels turned hospitals, whose post-war lives were complicated.

The Lake Norconian Club would become a Naval Weapons Assessment Center and later the California Rehabilitation Center. Today it sits abandoned and crumbling.

Vista Del Arroyo/McCornack General Hospital is now the Richard H. Chambers United States Court of Appeals.

El Mirador/Torney General Hospital burned down in 1989. Desert Regional Medical Center sits next to it along with a replica tower built in 1991, which honors the hotel's original.

Arrowhead Springs Hotel became a Hilton Hotel and, later, the headquarters of the Campus Crusade for Christ. Today it sits empty, a white elephant in the green topped mountains.

If walls could talk, one can only imagine the tantalizing tales these buildings would tell.

-

Restored with care, the 120-year-old movie theater is now ready for its closeup.

-

Councilmember Traci Park, who introduced the motion, said if the council failed to act on Friday, the home could be lost as early as the afternoon.

-

Hurricane Hilary is poised to dump several inches of rain on L.A. this weekend. It could also go down in history as the first tropical storm to make landfall here since 1939.

-

Shop owners got 30-day notices to vacate this week but said the new owners reached out to extend that another 30 days. This comes after its weekly swap meet permanently shut down earlier this month.

-

A local history about the extraordinary lives of a generation of female daredevils.

-

LAist's new podcast LA Made: Blood Sweat & Rockets explores the history of Pasadena's Jet Propulsion Lab, co-founder Jack Parsons' interest in the occult and the creepy local lore of Devil's Gate Dam.