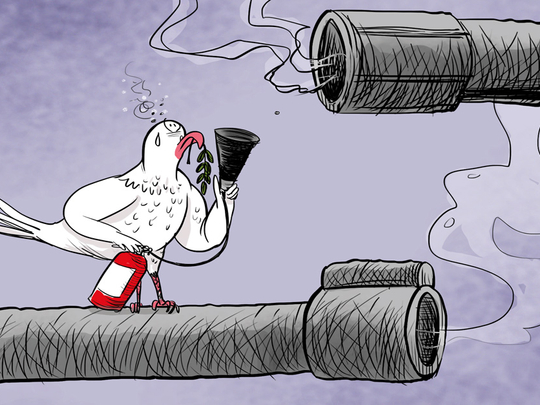

Technical Syria talks will kick off silently in Tehran on August 8, ahead of the next round of Astana negotiations later this month. They will be attended by officers and diplomats from Iran, Turkey and Russia, aimed at overseeing the ‘de-conflict zones’ agreements on Syria, reached by the three brokers in May. Although being hailed as a major breakthrough in the six year Syria conflict, the Astana process is still fragile and can snap and shatter at any moment. The technical talks in Tehran aim at adding flesh and bone to the Astana agreement, making sure that neither of the three brokers trespasses on the other’s territory, while outlining short-term or permanent zones of influence for regional stakeholders and their Syrian proxies.

Technically the four zones will ground warplanes and prevent tanks and soldiers from entering, enforcing a ceasefire in four parts of Syria, and uniting efforts of both warring factions in the war against Al Qaida and Daesh [the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant].

The first zone will be east of Damascus, where the Islamic Army of Mohammad Alloush is based in the strategic town of Douma since 2012. It went into effect on July 22, 2017 and was signed off by Alloush himself. The second zone will be in the northern countryside of Homs, presently held by Turkish-backed fighters from the Free Syrian Army. It went into effect on August 4. Thirdly, a zone will be carved out of the southern front, encompassing all territory from the Syrian-Jordanian border to the countryside of Suwaida in the Druze Mountain. It will include the town of Al Quneitra on the Golan Heights and was signed off by Presidents Trump and Vladimir Putin on the sidelines of the G20 Conference in Hamburg on July 7. The fourth and last zone — which will be high on the agenda on August 8, is the one in Idlib, a city in northwestern Syria held by Turkish-backed rebels since mid-2015.

During the last week of July, the city was overrun by Hayat Tahrir Al Sham (HTS), a coalition of Salafi militants that includes Jabhat Al Nusra, the Al Qaida branch in Syria, partially hampering the Astana agreement. Idlib is the only designated area in the Astana process that is still on-hold, where heavy fighting still prevails on a daily basis.

As for the remaining three zones, they will be co-run by a civilian authority from Damascus and natives from the cities and towns themselves, who technically will get pardoned after surrendering their weapons and accepting to work with Damascus, dropping their demands for downfall of the Syrian regime and halting all attacks on the Syrian armed forces. By next September, government schools and police stations will re-open in the three zones, while government troops will oversee the transfer of the wounded and elderly from East Ghouta to the hospitals of Damascus, pledging not to harass or arrest anybody during the evacuation process. They would also be required to allow the safe entry of humanitarian aid to the towns and villages in the countryside of Homs, Damascus, and Daraa.

The devil, however, is always in the details. The big three players will have to agree on who will man the checkpoints of the three existing safe zones, making sure that government troops don’t clash with their armed opposition. Peacekeepers are a must and so are monitors, preferably mandated by the United Nations. The original suggestion envisioned an international peacekeeping force, made up of “non-controversial” countries that are on good terms with Damascus, in clear reference to Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). Mohammad Alloush of the Islamic Army suggested Egyptian observers, while some even toyed with the idea of inviting Algeria or the UAE.

None of these states showed any willingness to send troops into a volatile war zone, prompting the Russians to act unilaterally. In mid-July 400 Russian military police were deployed the countryside of Daraa, tasked with overseeing the ceasefire, similar to 600 ones that were sent to Aleppo earlier in the year, after Russian troops re-took its eastern part from Turkish-backed fighters in December. Ten days ago, 150 additional Russian forces were deployed in East Ghouta, and photos of them went viral on social media networks, manning checkpoints and preparing to allow commercial conveys to and from the Syrian capital, for the first time in six years. More Russian soldiers are expected to appear north of Homs in the upcoming weeks.

What still needs to be agreed upon are several sticking points. How will the Astana process react to any violation of the ceasefire? Until now there is no method of punishment for either side of the Syrian conflict, explaining why the numerous breaches in Homs and Ghouta went by unaccounted in recent days. How will the Iranians be told that they cannot deploy troops on the ground in any of the four zones — simply because it will never pass with the armed opposition or their backers in Saudi Arabia — and rather, Tehran will have to satisfy itself with the pockets it currently has in Syria, in the Kalamoon Mountains overlooking Lebanon, at Shiite shrines within the Syrian capital, and on the Damascus-Beirut Highway. Thirdly, what will the parameters be for the three existing conflict zones and the forthcoming one in Idlib? Will rebels who surrender their arms be allowed to roam freely throughout Syria or will they only be allowed to commute within their ‘de-conflict zones?’ All of these questions are yet to be raised in Tehran on August 8 and their answers will either make or break the Astana process. Each of the big three players, after all, still has plenty of ammunition to kill the agreement if their interests are not properly accommodated.

— Sami Moubayed is a Syrian historian and former Carnegie scholar. He is also author of Under the Black Flag: At the frontier of the New Jihad